Time out from our celebration of National Poetry Month for a fun, witty short story about the nemesis of all writers: the adverb. Or is it? The Merriam-Webster Dictionary states, “Adverbs are words that usually modify—that is, they limit or restrict the meaning of—verbs. They may also modify adjectives, other adverbs, phrases, or even entire sentences. Got it? Read on.

The Great Adverb War

A Short Story by Russ Lopez

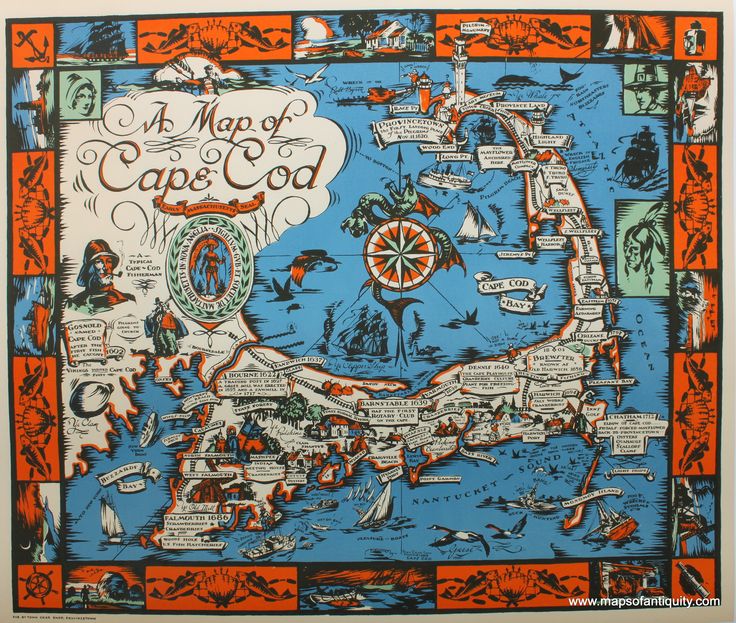

To nearly everyone’s surprise, the most contentious divide among Provincetown’s writers was not fiction vs. nonfiction, prose or poetry, or even the need for an Oxford comma, though Benji Camarillo’s husband had famously threatened to file for divorce over his refusal to use one after the penultimate noun in a series. No. The large, historic writing community in town violently splintered over adverbs.

The war began, as do so many literary controversies, during a night of hard drinking. Though the fog of war has obscured many of the messy details, historians agree that the first shot in this mostly verbal conflict was fired at the Lands End Saloon by Kevin Jenks. The L.E., as everyone affectionally calls it, is the kind of place where you go when you are too poor to drink at one of the more stylish bars in town or when no one else will serve you because you’ve had a few too many. The drinks have a stale cigarette aftertaste even though smoking had been banned twenty years ago and the entire bar has a tawdry, tired look about it, like someone should take a wire brush to scrub it clean. Don’t even think about the bathrooms. On the other hand, The L.E. has no pretentions. No matter who you are, when you walk in, the bartender will greet you with a friendly hello and ask what you want to drink.

Like most writers, Kevin had a second job to support himself despite his successful novels. One had even been made into a movie, though it had been so modified during the production process that only Kevin’s book title remained. Most writers teach or edit, but because he was drop-dead handsome — he looked like a Norse god — Kevin paid the mortgage on his million-dollar East End beach shack by whacking off online three nights a week. Made famous by his exceptional size and startling technique, Kevin was very popular among those who liked their men both intellectual and endowed, but the more money he made from sex work, the worse he felt about his primary means of support.

After a week that brought in more than ten thousand dollars in tips via an epic marathon of self-manipulation but saw only pennies from his literature podcast, where he poured out his most private thoughts on Keats and the latest fiction in the New Yorker, Kevin was in an ugly mood. Thus it was just after midnight on a sweltering July night that he stood up in the crowded bar, not an easy maneuver given how much alcohol was in his blood and the strange pitch of the L.E.’s floor that made the right side of the room two feet lower than the left. Looking around the room in a drunken daze, he raised his glass of cheap bourbon, served neat, as the crowd leaned forward to hear what he had to say. Or maybe they hoped to get a glimpse of his legendary member, but that was less likely because the bar was so dimly lit you couldn’t even tell whose hand was on your leg. After a brief hesitation — Kevin had forgotten what he was angry about — he proclaimed, “My goal in life is to see so few adverbs that I will be able to drown them in a bathtub.” He rewarded the resulting cheers by taking off his sweaty tee shirt and throwing it across the room where it landed on the head of a passed-out patron face down at the bar. “Vote for me and I will see to it that adverbs are wiped off the face of the earth.” With that he collapsed as alcohol combined with exhaustion from his online work knocked the now bare-chested writer to the sticky pitched floor. His long-suffering husband, a lawyer who was even better looking than Kevin, dragged him home while the bartender, used to this kind of behavior, added the shirt to his collection.

Normally, a speech like that would have died in midair, unremarked upon as it was made, unremembered two minutes later. More than a few hadn’t paid any attention to what Kevin said because they were carried away by the opportunity to see his body without having to spend money to get past his paywall. Many focused on figuring out which public office Kevin was running for as town elections had been held in May. But most, reflecting the strong level of respect for Kevin’s wordsmithing talents, began to debate the place of adverbs in our postmodern twilight of democracy.

Unbeknown to the slumbering Kevin he had ignited a firestorm, though he would never use that cliché. Carol Smythe, sitting at a table with two girlfriends more interested in making out with each other than with her, was also in a foul mood. A renowned Middle Grade author, she had just found out she had been invited to London to read from her latest chapbook but was distraught because the event was scheduled for the Wednesday of Carnival Week. She couldn’t decide whether to go to England for the honor or stay in town for the party. The resulting tension, and the rum she had been drinking since lunch, tore at her. Carol was born in the United States but her accent reflected her parents’ Barbados roots, her words lyrical and clipped. Her opponents in the war admitted that even when she was spitting mad, Carol was all poetry and grammatically perfect.

Proud of her Afro-Caribbean background that had given her thick, tight hair and warm brown skin, Carol was tired of the White cisgender male gatekeeping in publishing that worked against Black and queer authors. Kevin’s outburst reminded her of the fifty rejections she had received before her first novel was picked up to go on to become a best seller. Later she apologized to him, the two remaining close friends, but in the moment she took his words as a challenge to her writing style as well as that of her sisters-in-letters. As she stood up to argue with Kevin, she slammed her drink down. “A story without adverbs is bland and tasteless, not unlike mainstream American cooking and writing,” she shouted. Enjoying her anger, Carol forgot that the tabletop had a slant which paralleled the steep angle of the floor and watched as her glass slowly slid across the wet table. She continued: “Adverbs are like spices. Certainly, it’s easy to overdo them. But to omit them altogether renders the reading dull to everyone except those who have boring tastes.” She looked at her girlfriends for support, but they were deep into another sloppy kiss as Carol’s glass reached perilously close to the table edge. “Join with me to save adverbs,” she implored. “Let’s fight this together.”

As patrons began to argue over adverbs, no one noticed Carol’s glass glide off the tabletop. It shattered as it hit the floor, sending shards of glass skittering halfway across the room. The jarring sound momentarily silenced the bar as everyone wondered what was going to happen next.

The quiet was broken by Stephanie Park, who had written a popular series of detective novels set in Ptown, yet somehow never included gay men, lesbians, or Portuguese people, the three groups dominant in this part of Cape Cod. She jumped off her boyfriend Jimmy Costa’s lap to shout. “I second that. Long live adverbs!” A regular on the party circuit as well as the sous chef at Willie’s on the Beach, she was not afraid of boldly seasoning food or modifying verbs.

Stephanie’s girlfriend, an unpublished spoken-word poet who was about to leave Stephanie for a fling with Jimmy and a petite blonde real estate agent who just happened to be Jimmy’s wife, slurred, “Viva los adverbs!” as she leaned against the L.E.’s jukebox. Here, the slanted floor combined with a noticeable upward bulge to make even sober patrons feel seasick. “Viva!” she yelled again as she succumbed to vertigo and fell. The war was on.

The dispute caused a riot an hour later at The Pizza Box when Janet Gold, a straight woman who wrote gay male romance novels under the name Coyote Hanson, asserted her right to the sole remaining slice of pepperoni because she had never used an adverb in any of her twenty-two novels. “I dare you,” she told the bored woman at the counter who had heard similar boasts more times than she could count, “to search my entire output for an -ly and you will come up empty. Therefore, I should not have to wait for the next pizza to come out of the oven for a slice.” Though the men in her novels were polished, with flowing locks and toned muscles, Janet wore her hair up in a dispirited bun and hadn’t raised a sweat in years. She often insulted other townsfolk as she made her nightly pilgrimage for pizza and most considered her an uncouth potty-mouth and a gossip, making her a much sought-after dinner companion. Challenging everyone within earshot to contradict her, Janet paused to wipe her mouth with her sleeve and bellowed, “Adverbs are for sissies.” She snatched the last slice away from Travis McMillan who was too slow to react because the tall, willowy writer was pulling down his dress, which had risen up his butt while walking over from a night of dancing at The Barn. Polyester blends are the cause of many a spoiled outfit when the humidity is high.

“I use adverbs all the time because I am proud of who I am,” said Travis, a gay male writer of heterosexual romance books. Knowing who he was dealing with, Travis quickly unscrewed a shaker of red pepper flakes and poured them on Janet’s slice because she hated anything spicy. Enraged, Janet pushed Travis and soon the entire crowd at the pizza counter, which even on a slow night is a sweaty, pulsating, free-for-all of famished bears, rowdy drag queens, and oversexed twinks, broke into a frenzied shoving match. Travis was too much of a gentleman to touch a woman so he did the next best thing: he took a swing at her partner Jeremy, a mild-mannered wisp of a man who had the thankless job of being the town’s restaurant inspector. Thin as a pencil because he was afraid to dine anywhere out of food safety concerns, Jeremy easily deflected Travis’s fist. Despite him fancying himself as tough as Tennessee Williams, a long-ago Ptown resident, Travis didn’t have it in him to really hurt anyone.

There were twice as many people inside The Pizza Box as the legal occupancy allowed, all trying to get a slice as usual for this time of the night, so Janet’s shove and Travis’s blocked hit created a reaction that moved through the crowd like a shock wave, sending several people banging into those who were waiting in line to get into the restaurant. The queue went down like dominos and those slow to get up found that others had cut in front of them. The patio outside the restaurant was packed shoulder-to-shoulder, with most having sharp opinions regarding adverbs and no one in the mood to compromise. During the day, the patio’s benches were prime places to view the parade of tourists and townies passing by on Commercial Street; perhaps the views and the shade provided by what had to be the largest and healthiest Bradford pear tree on the Cape mellowed folks enough to permit some wiggle room on the use of adverbs. Tonight, however, the pro-adverb crowd defiantly claimed the left bench while those against overwriting clustered around the right one. Partisans shook fists at each other across the patio as others tried to leave, fearing that violence might break out at any moment.

Nearly everyone out after 1:00 a.m. can be found at The Pizza Box. On any summer night there are a couple thousand people milling about on narrow Commercial Street eating pizza, trying one last time to get laid, or looking for a good after-hours party. It takes a lot of patience to get a slice as the workers, fearing this might be the one night of the summer where the crowds stay home, only start making a new pizza once every other slice had been purchased. Even on the calmest of nights, the long wait for food puts people on edge. Given the anger over grammar that had seized the town that evening, just about everyone there was ready to mix it up.

Like everyone else in that teeming mass, David Ottinger wasn’t normally capable of violence. He had gone to Quaker day school and Brandeis, but as he stood lost in thought regarding the proper role of adverbs in contemporary American literature, someone stepped on his new white shoes. David exploded. He desperately wanted to be declared Provincetown’s next poet laureate, though he hadn’t written anything since a haiku in high school. In pain, he angrily pushed the drunk off his foot. That led to a counter shove and within seconds, everyone on Commercial Street, including two shirtless pedicab drivers, the town’s only chiropractor, and an elderly couple who had made a wrong turn up Cape and was bewildered because they couldn’t find the bridge to the mainland, were slamming, pushing, and foot-stomping each other. At one point, someone fell against the large window of the liquor store across the street and the glass shattered, taking down the neon sign that blinked “Booze! Smokes!” all night long. No one was seriously injured; the crowd was too well behaved even to loot the store, but it took the police until dawn to restore order.

Hung over and feeling sheepish over the violence, many woke up the next morning hoping the night’s controversy was a bad dream, but the war quickly reasserted itself. The natural-born peacekeeper and well-respected owner of Herring Cove Books, Don Franklin, offered to mediate. But rumors that he was methodically going through every book in his inventory to cross out adverbs with a black marker made the pro-adverb side reject his offer of negotiations over brunch. Then the anti-adverb contingent heard that Don was secretly providing books with adverbs to those who were too meek to buy them openly. They walked out as both sides hurled insults at Don, the sweet women who owned the tea store across the street, and a film crew that had stopped to ask for directions to Norman Mailer’s house. Since no one had read any Mailer in decades, despite the many summers he had spent in town, nobody knew where he stood on adverbs. This allowed everyone to be offended by him.

Meanwhile, though the Unitarians proudly proclaimed they were open to everyone regardless of what they believed about modifying verbs, a loud demonstration on the front lawn of their Meeting House in favor of adverbs drowned out their well-attended service. Barely a block away, others were burning adverbs in effigy in front of Town Hall with the smell of smoke and the near-constant blare of sirens convincing many that the entire town was in flames.

That afternoon in the library, Cate Thompson thought about admonishing everyone who had come to hear Robert Vernon read from his riveting new book on the extinct wildflowers of the Cape Cod National Seashore to keep their opinions on adverbs to themselves. Robert was an hour late showing up, giving Cate time to decide that last night had been an aberration and there was no need to scold. The head librarian was wrong. The first question from the audience was about Robert’s stand on adverbs, which he voraciously condemned out of fear the mob might go after split infinitives next. The resulting shouting and cursing alarmed Cate, so she summoned the police but the officers couldn’t come because they were busy breaking up a fight at Boy Beach two and a half miles away in the National Seashore. Two hirsute bears dressed only in leather thongs had gone belly to hairy belly when one accused the other of “Rowing his boat gently down the stream.” In the tense days of the war, those were fighting words.

Both sides appealed to the Select Board, that august group of five who governed the town. Hoping to ride the emotions of her constituents, Beatrice Lopes proposed putting adverbs to a vote. She told people she would make adverbs the central plank of her reelection campaign next year, though she was careful not to tell anyone where she stood on the issue. But her fellow board members were too timid to involve themselves in the controversy and kicked it to the Town Manager. In the realm of the crazy, it is said, the half-nutty are king, and the Town Manager underscored his reputation for calm competency by promising to deliver a study in late October. By then, of course, the controversy had been forgotten and his report, never read, is supposed to have been deposited in a locked box cemented under the foundation of the new, and equally controversial, funicular to the Pilgrim Monument.

The war, like so many other conflicts, finally ended not with one side defeating the other but with everyone being too exhausted to continue to fight. There are still occasional skirmishes. About every other month a letter in one of the local papers carries on the same tired arguments, and rumor has it the owner of The Barn asks every new hire where they stand on adverbs. If they answer wrongly, he refers them to his rival nightclub, The Sand and Sea. He has his standards.

***

Russ López is the author of six nonfiction books as well as book reviews and journal articles. After an extensive career of community organizing and social justice advocacy, he is the editor of LatineLit, a magazine that publishes fiction by and about Latinx people. The Matchmaker is part of a planned collection of short stories tentatively titled, The Lesser Saints of Silicon Valley. A California native, López has degrees from Stanford, Harvard, and Boston University. He currently divides his time between Boston and Provincetown, Massachusetts.