After graduating from college in 2013 with a degree in art, I spent the next five years maintaining a sharp focus on honing my craft as a painter. Countless studio hours were matched with even more time pursuing opportunities, schmoozing with gallerists, and making my presence known within Boston’s, and the greater Northeast’s, vibrant art communities.

While each year yielded great leaps in my technical dexterity and academic proficiency as a painter, the art was virtually devoid of the most important component that separates art from craft . . . and I just couldn’t see it. Or, perhaps I could see it—I just didn’t want to.

The debates between, “what is good art” and “what is or can be art” have been raging on for years – particularly since the mid-19th century with the birth of the Impressionist style and subsequent advent of modern art. Since art is necessarily subjective, these debates will happily retain an inextinguishable flame.

One debate that we can put some definition to, however, is what separates an object considered to be art from one that is a product of craftsmanship alone. Craft typically refers to the technical production of an object. The hand-carved decorations on a finely built bookcase, a guitar player who has knowledge of hundreds of scales and plays them at lightning speed, and even a photorealistic painting are all examples of exceptional craft. The intention is to refer to nothing else beyond the object; that is to say, when we typically have an emotional response to a piece of great craftsmanship, our reaction is one of awe and reverence toward the skills necessary to create such an object.

So, what makes something art?

On a first pass, we may hesitate momentarily to produce an articulate definition (particularly at a bar after several Scotches with an enthusiastic art buff after an opening; I have been here a few times). But almost all of us instinctively know what art is — or at least know it when we see it. We remember great pieces of art because they resonate with us on an emotional level. They tell a profound story or connect deeply with our own story or both. We are moved, sometimes to tears when we discover symbolism and allegory in great works of art. In short, what separates art from craft is that art bears the indelible stamp of the human condition. That is, after all, one of the quintessential roles that art and the humanities play in the human story. Science may inform us as to how the world works, but art guides us how to be in the world.

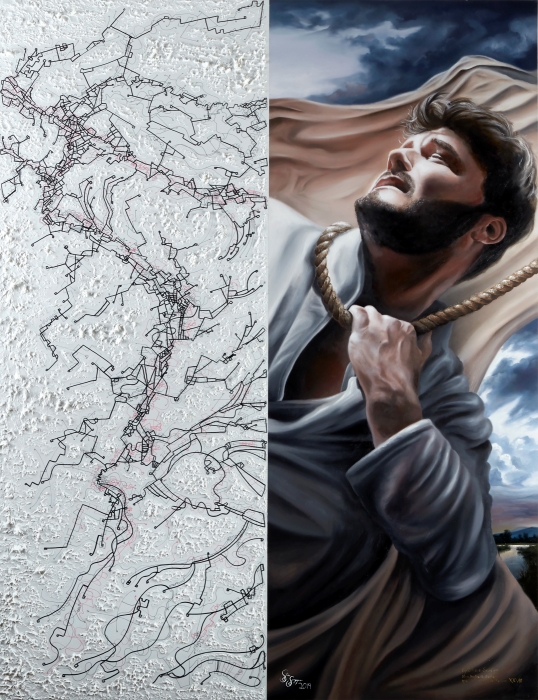

It wasn’t until last summer, while on a painting retreat in the Hudson River Valley with artists Alex and Allyson Grey, that I had the most important creative breakthrough of my life. It was proposed to me directly that I may have been, to a great fault, a lot more guarded in my creative expression than I would have liked to admit. While my portfolio had consisted of impressive work, rich in allusions to my intellectual interests, it was missing the stamp that indicated “Steve and only Steve was or could have been here.”

This lacking in the work was certainly not because I simply had no story to tell; quite the contrary. I was deliberately avoiding focusing on parts of my story because I was afraid. I was afraid of not only exposing myself to the public eye but, even worse, of having to confront some of the darker passages of my life through the medium of painting. The thought of using art as a pilot for therapeutic storytelling meant intertwining what I was most passionate about in life with, well, my life.

Up until that point, the five years I had been painting coincided with many significant life changes. Pursuing my career goals, getting married to the love of my life, moving to Boston and five very significant (and soon to be just six months later) deaths in my life—including the suicide of my best friend. Balancing everything while still producing my best creative work was, at times, a challenge. And spontaneous, often booze-fueled emotional outbursts were an indicator to me that I had unresolved conflict that needed to be confronted. It was Allyson Grey who identified the missing link in my work, and Alex Grey who gave me the words of wisdom, “You are an artist. You have to confront your issues as one.”

I had always kept my identity as an artist separate from much of my personal and emotional inner narrative. It was because of this that what I was producing was only satisfying my desire to develop my craft, and not my art.

Since this creative awakening, the past year of my life and work has been by far the richest to date. In nearly everything I create I attempt to refine my academic prowess, explore my interests and allow my emotional narrative to take center stage. I am emotionally comfortable and am always eager to display new work for public consumption, even when the subject may be slightly uncomfortable or exposing. Every portrait is a character of significance, every landscape Is one in which I have personally stood in awe, and every brushstroke has me in the grip of confidence to continue growing and developing, regardless of how difficult life can get.

* * *

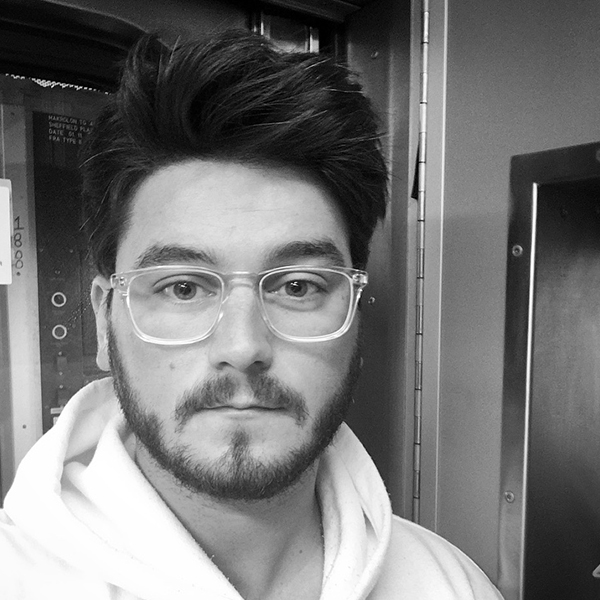

Steve Sangapore is a contemporary oil painter based in Boston, MA. He is a 2013 graduate of Albertus Magnus College in New Haven, CT, where he earned a B.A. in studio art and graphic design. Using vastly different stylistic approaches with various series’, his work can be described as an amalgamation of realism, surrealism, and abstraction with thematic focuses on the human condition. His unique take on composition, subjects, and structural execution has led to his paintings being exhibited nationally and published in art magazines and journals, including Art Business News, The Boston Globe, Creative Quarterly, Artscope, and E-Squared Magazine. Steve has been the Fictional Café’s Fine Arts Barista, designed the cover for the Cafe’s first book, The Strong Stuff, and has been featured here as well. You can see Steve’s art on his website and on his Instagram.

I have nothing but esteem for Mr. Sangapore’s discussion between life and art, but disagree on one particular point that “art guides us how to be in the world.” As my life’s work has been in theatre, both artistically ,critically, and as teacher,I have never looked at a play so didactically, as per Bertolt Brecht, but art in general as guiding us to how we are in the world and beyond. I will never forget climbing the main stairway in the Metropolitan Museum of Art to be confronted with El Greco’s “the Cardinal,” time stopped; I was in a sublimely inexpressible moment, nothing to do with comportment but transcendence.