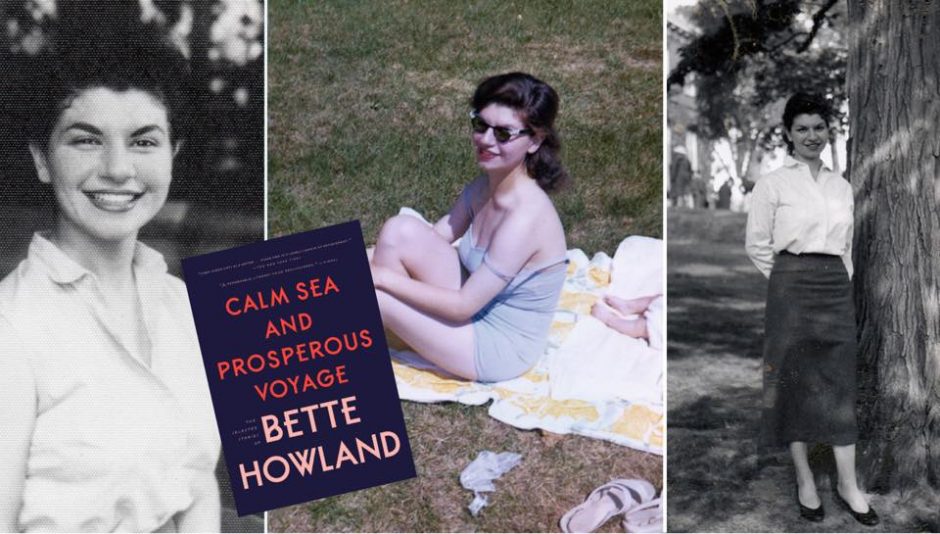

Photo Credit: Magic City Books

Editor’s Note: We’re excited to announce two pieces of creative nonfiction by FC member and former Featured Writer, Raymond Abbott. He details two events from his career as a writer.

Bette Howland, Chicago Writer

Bette Howland has been dead for more than two years. I have had ample time to consider some of the things written about her. She received the MacArthur Award in 1984, and receiving the grant seemed to compel her to stop writing. I had heard of this kind of thing before, but I don’t know that I believe it. What slowed her down when I knew her was the pain she suffered when a man she had been seeing for a long time unexpectedly married another woman.

Bette wrote and published several books, including W3, Blue in Chicago, Things to Come and Go, and one published after her death, Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage.

I first met Bette at the MacDowell Colony, before the MacArthur grant. She seemed reclusive, often missing meals, something I never did. MacDowell feeds you well.

Writers often put out examples of their published works, and I placed on a table a novella I wrote about the Sioux of South Dakota. I once lived on a Sioux reservation for a time. Bette read it and we talked, got acquainted, and when we left MacDowell, stayed in touch, sometimes speaking by phone. This went on for years. She visited me one time in Louisville. She liked Louisville, even talked of moving here. She had been a wanderer much of her life.

She impressed me with how many people she knew in publishing, other writers, too. Saul Bellow was once her lover, and that tidbit of gossip has been repeated over and over again, much too frequently for my liking. I don’t recall her mentioning Bellow or his work except for one time when she said that as a young man, he was break-your-neck good looking.

She suffered with arthritis, but when she visited me, she was well enough to walk around my neighborhood. She didn’t dress extravagantly, not being especially stylish, and usually wore jeans. Her hair was a bit grayer than I remembered at MacDowell. Of course we talked about writing and writers. She told me a story about Richard Yates, a man I knew slightly. She knew him well. Bette was a big fan of James Farrell, and Yates knew this. She wrote about Farrell in newspapers, interviewed him once too, I believe. Yates may have been having fun with her one day, being a bit mischievous, when he told her he had never written a novel as bad as . . . Then he mentioned one of Farrell’s lesser works. She didn’t reply, being polite I guess, but she told me later what she thought. Yes, Richard, but you have never written anything as fine as the Studs Lonigan Trilogy.

She talked a lot about her two sons, and their promising careers. The same too, when grandchildren came along.

She didn’t have much to say about politics, except when 9/11 happened. Then she wrote me that she was glad George W. Bush was President, because he could be expected to respond appropriately. She meant forcefully. Probably she was not a fan of President Trump, but I don’t know this. All things Jewish mattered to Bette, and the security of Israel was very important to her. So I would not be surprised to learn she respected Trump, at least when it came to his policies designed to weaken a major foe of Israel, namely, Iran.

When it came to writing, she was not one to follow the crowd, saying frequently how she seldom came upon writing today that she had much respect for.

When last we spoke, Bette was living in Tulsa, close to one of her sons. I had not heard from her in a long time, so I called her. Usually, she called me. The conversation was muddled, confusing and brief. I am not sure she knew who I was, which made me sad. C’est domage.

**

My Friend Barbara

Many years ago I was given a literary award from the Mary Roberts Rinehart Foundation. It was for $175, and was an encouragement to finish an American Indian novel I was then writing. “Not enough to quit your job,” I remember was a line from the letter I received from the foundation’s rep, Barbara.

And from thereafter, Barbara and I kept in touch for many years. Mostly we wrote letters, and I once visited her in New York City in her high-ceilinged, spacious apartment in the Village. It was an elegant place, and she loved it. It was expensive, and she feared she could not afford the rent for much longer. She no longer worked for the foundation, although she spoke often of how much she had enjoyed her position there. She was a victim of a series of cutbacks.

Barbara was a vibrant woman, bubbly and smiling and very upbeat with me, but I suspect she was that way with everyone. She was herself a writer of short stories and novellas. She told me that she had often tried to publish in the New Yorker, only collecting many rejection notes for her efforts, as did we all. Still do.

By coincidence, Barbara and I published our longer fiction with the same small press in Boston. For me, the short Indian novel led to good things. First, it was a ten-thousand-dollar grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, followed several years later by a $25,000 writers award from a New York Foundation. In those years it was tax-free. I was on a roll.

You had to be nominated for the $25,000 prize, you could not apply. So you were left guessing as to who put your name up for consideration.

Barbara and I meanwhile continued our correspondents. I knew she struggled mightily in expensive Manhattan. She had several part-time jobs, secretarial in nature often, but nothing steady. Yet she was always sunny in her letters.

I had my problems in Louisville, including a divorce, but they were small compared to those facing Barbara. She developed cancer in her kidneys. I believe there was one surgery, but I presume the cancer could not be contained. I didn’t get a lot of the particulars.

As a past recipient of this large New York award I automatically became a nominator for future grantees. I decided to nominate Barbara. The way the deal works is, you obtain from the person you are considering for the award copies of their work (unpublished as they often were). And you do this any way you can manage, but you are not allowed to reveal to a would-be recipient why you are collecting copies of their writings. Not always an easy thing to do.

I knew the rules, but they did not keep me from telling Barbara what I was up to.

Her death, in my estimation, and from what others around her told me, was not far off, and I knew the nomination was for her an exciting development. It gave her something to look forward to, or so I wanted to believe, anyway. Immediately she forwarded me pages of a novella, a sample of her work. I didn’t notice the manuscript was an original, or if I did, I thought nothing of it. I assumed she kept a copy. She did not.

When the awards were announced months later, she did not, regrettably, get one, and shortly thereafter she contacted the foundation seeking return of her manuscript, the original novella. The pages were immediately returned to her, and within days I had a strong letter from the foundation’s director. He gave me hell for revealing what I had to the person I nominated, that being Barbara, of course. The man was pissed, and if he could have rescinded my earlier award, asked back the $25,000 I was given, I think he might have. Under such circumstances I would have felt duty bound to refer him to my ex-wife Mary for collection, and with the admonition, “Best of luck!”

I waited what I viewed as a reasonable period of time and wrote back the foundation director, explaining how the lady I nominated was dying of cancer and learning from me that I had nominated her for the prestigious prize could, and probably did, improve her spirits, gave her a bit of hope in a desperate situation. That was what I liked to believe. And the quality of her writing, I reminded the man, was never in question. She was a pro. I resisted telling him I would do it all over again if the circumstances were similar. Perhaps he guessed as much.

I never heard back from the fellow. Barbara was dead in about a year. And I was not again asked to nominate another writer, but my guess is that you the reader already figured that out.

I know foundations cannot be expected to fund the dying, I understand that, but I myself would allow exceptions in a world where I make the rules.

***

Raymond Abbott is a social worker in Louisville, Kentucky, having served in VISTA on a South Dakota Indian reservation. He has received a Whiting Writers Award and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Kentucky Arts Council.