Editor’s Note: It isn’t often we’re presented with a novella-length submission, but this one was too good to pass up. What makes it extra special is that it’s the author’s first published work. Victoria “Tori” Merkle’s “Elephant Tadpoles” will appear in three segments this week – today, Wednesday and Friday. We hope you’ll appreciate it as much as we baristas did, and will share your Comments with the author.

℘

Elephant Tadpoles

by

Tori Merkle

Part I

“Come on, girls, school in an hour!” our mother, Grace Hayward, ushered our two blonde heads down the hall. I was five steps faster, my messy pigtails bobbing up and down as I skipped into the kitchen. My bare feet slapped against the dark oak floor and my plaid skirt, its waistband folded twice over, could have slipped off any minute. It must have been driving my mother crazy, but we could never find anything that fit me right because my legs were too long for my tiny waist.

Lisa walked alongside Mother, her small hand clasped around Mother’s. “Mum, it’s too loose,” said Lisa. She fidgeted with the elastic of her braid, sulking. “It looks bad!”

“Don’t be cheeky, love,” said Mother, “we’ll fix it.” She kissed Lisa’s hand and hurried her around the corner where the wood transitioned into white marble.

Edmund Hayward turned away from the frying eggs to greet my hug. “Good morning, monkey—jam or egg on your muffin?”

“Um.” I bit my finger, thoroughly conflicted.

“Jam for me, Daddy,” said Lisa, “please.”

“As you wish, Little Miss.” Father slid a plated English muffin and a jar of jam towards Lisa’s spot at the table. “Hello, my dear,” he said, planting a kiss on Mother’s lips.

“Good morning,” Mother said, yawning, as she spread the jam onto Lisa’s English muffin.

“Can I have both?” I asked. “Half and half.”

“Easy enough,” said Father. He slipped a warm fried egg onto half of my English muffin.

“Yay!” I said. “Thank you, Daddy.”

Mother passed him the jam, and he covered the other half quickly before moving to the teapot to pour his wife a cup.

“Thank you, dear,” said Mother.

Father massaged her shoulder gently with his thumb and poured some tea into Lisa’s little yellow cup dotted with pink flowers. When he held the teapot up to me, I wrinkled my nose. I hated tea. He shrugged and topped off his own cup, then passed Mother an egg and meat breakfast.

“You’ve got to start drinking tea, soon,” said Lisa, “it’s what all the ladies do.”

“No I don’t,” said I, “I’m only six.” I took a messy bite of the English muffin with jam and continued through my chewing, “Besides, who says I have to be a lady? You’re not a lady.” I couldn’t imagine, at that point, that Lisa would ever truly be anything other than my older sister.

“I am too!” Lisa said.

“If you say so,” I said.

“I am! Why do you have to be such a brat?” Lisa asked.

“I know you are but what am I?”

“Girls!” Father hollered. We quieted.

“She started it,” said Lisa.

“No, you said I have to drink tea!”

“Oh, fiddlesticks,” said Mother, “the hair.” Mother left her plate and rummaged for a brush in the lumpy purse on the counter. After finding it, she stood behind Lisa’s chair and unraveled her braid.

“I can do that, dear,” said Father. “I already ate.”

“You have to catch the train.”

With both of them preoccupied with my sister’s hair, I took the opportunity to stick my tongue out at her. She twisted her face as if I were the most despicable creature she had ever seen. I pinched my cheeks to add to the effect. She mouthed the word weirdo and rolled her eyes. Rather pleased with myself, I laughed, silently, and made another face. This time, she reciprocated with a funny face of her own.

“Don’t think the man of the house can braid, do you?”

Lisa and I snickered.

“It’s really not a problem,” said Mother.

“Please? I want to. You know how I love doing my princess’s hair.” He nuzzled and kissed Lisa’s head, and she burst into giggles.

“All right,” said Mother. “Okay.” She kissed Lisa’s cheek and returned to her seat. Father ran his fingers through and brushed through the wispy blonde curls, working them into a neat French braid.

“How is the spelling list?”

“Good,” I said.

“Liar,” said Lisa. “She did wretchedly.”

“Meanie!”

“It’s not my fault you’re a terrible speller.”

“Nonsense,” said Father, “my girls aren’t terrible at anything.”

“Help your sister study again, Lisa,” said Mother.

Lisa groaned.

“And no cheekiness!”

“Yeah, you hear that?” I said, knowing I had won. “Ladies aren’t cheeky, you know!”

“Fine!” Lisa said. “Spell wretched.”

“That’s not even one of the words,” I said.

“See, she can’t spell it—”

“Give her the right words, love.”

Lisa surrendered and went through my first grade spelling list. Father finished Lisa’s braid, kissed us all goodbye, and left the house with his briefcase in hand. Mother abandoned half her breakfast, fit a safety pin into the waistband of my skirt, and hurried us into the station wagon for the familiar trip to our private New England day school.

When we would get there, Mother would remind us of our etiquette classes after school and Lisa would ditch me for the huddle of friends waiting outside of the middle school. “Don’t bother Ms. Marcy or get in trouble today, okay?”

But it didn’t make a difference. It never made a difference. I went to find Ms. Marcy before Morning Meeting, because she told the best stories and let me help mix the paint colors for the day. Then I found Mr. Watson, because he let me feed the lizards. Ms. Marcy and Mr. Watson were the only teachers who let me do anything and that’s why I always got in trouble with the others. That’s why I got sent to the dean’s office once a week. Her name was Mrs. Elwood. It was always for something stupid, but she’d call my mother at work anyway.

That Tuesday was particularly memorable. I sat on the tiny wooden bench just outside of her office with my arms crossed. I kicked my feet and trying to listen through the wall. It was easily done because the walls at Cheshire were all so thin, as if they were trying to convince the world they didn’t have any secrets.

I was certain I was in the right and Mrs. Elwood simply didn’t understand. She was out to get me, I was convinced. It was an injustice. I was a martyr.

“Mrs. Hayward?” she said.

“Yes, this is she,” my mother responded.

“This is Cheshire Day School, we’re calling about your daughter.”

“Joan?”

“Yes, Lisa is doing quite well—but, Joan, you see…”

“I’m so sorry. What is it this time?”

“She let the tadpoles out of the biology room.”

“Pardon me?”

“We had tadpoles for the students, you see. For them to learn about metamorphosis. She got some of the other kids to help her release them into the river behind campus.”

They wanted to join me, though. We made hats with Ms. Marcy’s art supplies. They had feathers and badges that said Tadpole Liberation Squad. We marched into the classroom during recess, singing our battle song.

“Oh, dear,” Mother said.

“She told them, ‘be free! Don’t let yourself rot away in this wretched prison!’”

There was more to it, of course. I hadn’t just told them to be free. I had told them to go, swim away, and be frogs. Or, better yet, to not be frogs. I told them to be elephants, or birds, or lions. Because nobody could tell them what to be.

“I am so sorry. We don’t think Cheshire Day is a prison. We’ll buy you a new stock of tadpoles.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Hayward, but we have another concern.”

“Yes?”

“Some of the faculty are worried about your Joan. I’m sorry; this is difficult to approach. Mrs. Hayward, is your daughter happy?”

“What do you mean? Of course she’s happy. She’s the happiest kid we know. You think something’s wrong with her?”

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to offend you. I’m just trying to say… she’s a bit different, isn’t she?”

“Mrs. Elwood, are you calling my daughter mad?”

“No, no, not at all. We at Cheshire value individuality.”

Yeah, I thought, tell that to the tadpoles.

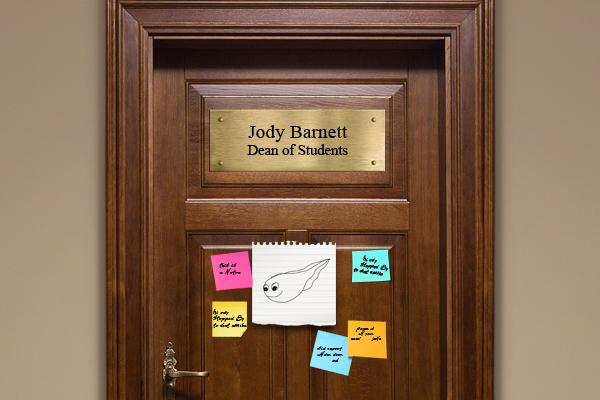

Thirty-one years later, and I had a picture of a tadpole taped to my office door. I was the Dean of Students at Weston Academy and the exiled sister of Lisa Collingwood.

℘

I spent the entire day wondering what would be the most surprising to them. It might have been the sheer irony of me, the difficult child who couldn’t handle private school, winding up the dean of a private boarding school that was, perhaps, even worse than Cheshire. It might have been the fact, embarrassing as it was to them, that my sister was desperate enough to seek my help. It might have been my red hair. It might have been the fact that I spoke in a British accent, now, naturally. But I thought that would mostly make my sister jealous.

I also tried to imagine what would be the most shocking to me. Eight years is a long time. The last I had seen them, Bridget wore bouncy pigtails and Sophia had just learned to braid her own hair. I wondered what mistakes they had made since then. Samuel, like my own father, was under the impression that his daughters could do no wrong. He called them extraordinary and reminded them regularly that they would always be worthy of that title. And they were. They were the most extraordinary little sprites in the world. They had a kind of glow around them that made everyone want to be a part of their lives. Samuel and Lisa would’ve carefully raised them to keep it that way.

I watched the line progress through the doors of the Masterson Center, the oldest building on campus. It had stark white interior walls with an elaborate wood trim, lined with placards listing alumni and prize winners. There was marble tile throughout the lobby. The room had two seating areas of old paisley couches and end tables complete with vases of pale flowers and stacks of school viewbooks. At the center of the space was a deep mahogany table and framed portrait of Weston Academy’s founder and first headmaster, Alexander Weston.

The line wound around the clothed tables we had set up, which formed a U-shape with the mahogany table in the middle. A member of the administration sat at each table. Everything was Weston burgundy, from the tablecloths to the folders we had labeled with the school seal and new student’s name. We each had a stack of forms and orientation materials to hand out. We wore our widest smiles and shook everyone’s hand with the right amount of pressure and eye contact. I was quite good at it. I suppose I have my childhood to thank for that.

“My name is Bridget Collingwood,” she said. “I’m a new junior here.” I didn’t like that. Her name wasn’t Bridget Collingwood. It was Bea, and she was my niece, and I should have been able to hug her. But Lisa’s conditions were clear. It was a blank slate, a new start for her. She couldn’t have any prior connections, especially not any to me.

“Nice to meet you, Bridget,” I said. The collar of my blazer felt tighter around my neck and a hot sweat dampened the hand I reached out to her. Her handshake came in firmly, but her hand turned into a sack of sticks the second I enclosed mine over it. “My name is Jody Barnett. I’m the Dean of Students here. I hope you all are enjoying your welcome so far.”

“Yes,” said Lisa. “It has been very nice. Thank you.” Her smile was tight and she kept her gaze crooked.

I looked directly at her, because that’s what the Dean of Students does. I fixed my eyes on her face and waited for the moment she would accidentally reveal herself.

“My name is Lisa. And this is my husband Samuel,” she said.

Samuel rocked back on his heels and nodded curtly.

“We, um,” Lisa continued, “we understand there are some events planned?”

I remembered our old game, when I followed her sentences with my own cocky interpretation, filled in the blanks and exposed the things she had filtered out. It was very amusing, and she hated it. She rolled her eyes and discredited my work, again and again. And again and again, I would keep it up until she eventually threw something at me, lost her temper, or marched away.

“Yes, we have an itinerary for you here,” I said.

“Oh, good. Lovely.” (Translation: I’m sure you do, you colossal bitch.)

I handed her a burgundy folder. “There is a luncheon for parents and students in an hour and a half.” I pointed through my copy of the schedule. “Then you’ll part for separate orientations—so you’ll want to say your goodbyes.”

“Wow, so soon?” (Translation: I’m sure you’re excited for that, you colossal bitch.)

“We find that it’s good for new students to get acquainted with their peers as soon as possible. It’s difficult when the parents leave, you see. We don’t want anyone to feel alone.”

“Understandable,” said Samuel, realizing his wife couldn’t restrain herself much longer.

“I’m 20, now,” said Sophia. “I go to Yale.” She was instantly mortified. Lisa cringed and Samuel squeezed her hand and rubbed Sophia’s back. Bridget looked off to the side, and I caught a small grin on her face.

“Oh,” I said, “good for you. Yale is a great school.”

Sophia nodded feebly and Bridget hid her growing grin with her hand.

“Welcome to Weston,” I said. “Bridget, have you met your advisor yet?”

Bridget shook her head.

“Let’s see,” I said. I thumbed through my papers. “Her name is Mrs. Anderson, she teaches psychology and forensics and is also the track coach. She lives on campus with her family, actually in your dorm. You meet with her and the rest of your advisory for half an hour every week, but you can stop by her apartment any time. She’ll help you figure out your classes and sports selections, and anything else you might need.”

“Sort of like your mom away from home,” said the assistant dean, sitting next to me.

Lisa’s lip twitched.

“Yes,” I said, “that’s how many of the students describe their advisors.” I watched Lisa’s face and pledged my allegiance to the vengeful spirit inside me. “The rest of the faculty, of course, are also always willing to help.”

Lisa dug her fingers into her palm, smiled, and nodded. “That’s great,” she said, “I’m glad she will have a strong support system.” (Translation: Stay away from my daughter, you colossal bitch.)

“Thanks,” said Bridget. “Um, should we start moving me in?”

℘

The first time Bridget came to my office that year felt wrong and right.

I remembered the little girl I used to pick up and spin in circles. I always gave her Oreos, categorized by Lisa as junk food and strictly banned from the Collingwood household, and art supplies. We always had a new project to start. We made crowns out of weeds and candles out of reclaimed vessels from the thrift store. I taught her how to paint and then told her to disregard everything I said and do it her own way.

Then I felt the dark, restless weight of all the years we had missed. She walked in a beautiful and storied teenager, who had already fallen in love and fallen apart. Her smile was the same, though. Bright, dimpled, and enigmatic. And her eyes, magnetic and unruly.

“Bea, you made it!” I said. I was so tempted to scoop her up and spin her around like I used to. I wanted to talk to her for hours and hear all about her life, all the drama and hardship. I wanted to have some kind of picture of everything I missed.

“Hi,” she said, “Mrs. Barnett? I’m Bridget Collingwood; I’m new here. You told me to stop by?”

“Oh,” I said, “yes.” I stood up, stepped away from my desk, and ushered her into one of the plush seats across from mine. I made sure every step was composed. “I just wanted to check in.”

“Oh, okay.”

“How is everything? Your classes, your dorm? Are you all settled in?”

“Almost. Just trying to bring order to my chaos. Never was good at that. But classes seem okay. I’m excited for Advanced Painting.”

“Good, good. Yes, Mr. Coleman is very well-liked.”

Bridget grinned to the floor and fiddled with the sliding puzzle I kept on the coffee table with various other gadgets to keep nervous students busy. She pressed her lips together, struggling to suppress a grin. I suspected the impersonally professional phrase that just came out of my mouth was probably pretty amusing to her. “Yeah,” she said, “he seems like a cool guy.”

“How’s your roommate?”

“Good. Her name is Hazel, she seems… nice.”

If I heard the word good again, I might have lost it. “Ah, yes, Hazel is a sweetheart,” I said. “I hear you have some classes with her, that’s… great.”

Bridget buckled into laughter. “Alright, alright, I surrender.”

“Good, finally! Can I hug my niece now?”

“Yes, of course.” Bridget stood to accept my embrace.

“I missed you!” I rocked her back and forth. “How old were you when I last saw you? Ten?”

“Yes,” Bridget said. “Well, we Skyped a little when I was in middle school. But, yeah.”

“That’s not nearly the same.”

“Yeah, I know.” Bridget returned to her seat and I took the red quilted seat next to her.

“Pretty sweet place, huh?”

“Yeah,” Bridget agreed. “You’ve got the regal suite here.”

I laughed. “You should see the headmaster’s office, it’s insane.”

“Is that one of those fancy executive chairs?” Bridget looked at the plush leather rolling chair behind my desk.

“Yes!” I moved towards it and rolled it over to Bridget, twirling it around for dramatic effect. “You want to try? Go on, do it. It’s really comfortable.”

Bridget laughed and plopped herself into the chair. “Yes, yes,” she said. “10 out of 10.”

“Just 10? I would give it a 12, at least.” I returned to my seat. I couldn’t take my eyes off her.

She grinned sheepishly and did a spin in the chair before meeting my eyes. We were silent for a long moment as I remembered every last detail I knew about her.

“Funny how things work out, huh?” Bridget said.

“Yeah,” I said. “Yeah… So how are you?”

“Like, today? Or in general?”

“Both. I’ve certainly missed a lot of your days.”

“I’m doing… okay,” Bridget said. “Things got pretty bad.” She pulled her arms and legs in, her cheeks flushed and gaze lowered to the floor. I saw the giant lump in her throat, stuck there as if she were scared to swallow it. It was unsettling. I never expected that little girl to shy away from anything. “Too bad to really fill you in on, actually. But they’re okay now… I’m happy to be here.”

I had an urge to squeeze her hand.

“And it’s not your fault that you missed a lot of my days. It was my parents, I know that.”

I thought her throat’s lump must’ve moved onto me.

“I’m sorry they did that,” she said.

“No, no…I mean, yeah. I’m sorry too. How are they? Your parents, I mean. Your mom…”

I squeezed one of the stress balls I had set out for my students and adjusted the tiny ceramic tadpole on the table.

“They’re good,” Bridget said. “Both of them. Still trying to do what’s best.”

“I bet,” I said. “I give them a lot of credit for that.” Seeing what I was missing out on, however, I harbored more resentment for them than ever.

“Yeah, me too.” Bridget started to fidget too, curled her fingers around each other and blinked far more than usual. “Um, Aunt Jody,” she said, finally. “I never really knew what went wrong with you two. You don’t have to tell me, of course, I mean, it’s been so long. But, can you?”

I don’t know why, but I wanted to start with the good stuff.

℘

Coming Wednesday, July 11: Part II of “Elephant Tadpoles.”

Victoria Merkle, also known as Tori, is a rising junior at Wellesley College studying English and creative writing. She lives in Brighton and interns with the Independent Publishers of New England. Now twenty years old, she has been passionate about writing since receiving her first creative prompt in the first grade.