Editor’s Note: Here’s the second instalment in Tori Merkle’s novella, “Elephant Tadpoles,” which began on Monday. The concluding Part III appears here on Friday, July, 13.

Elephant Tadpoles

by

Tori Merkle

Part II

Summers at the Hayward Estate in the British Isles were lustrous and tender. The property felt endless to me, the rows of grape trees in the vineyard stretched on and on until they blurred into the soft green hills beyond them. I wished I could trace my finger along the landscape and feel its nooks and crannies. I thought there must be entire worlds hidden in the ravines between the hills.

There were more than enough ravines to explore on the property, though. The stone-walled house had three peaks like a castle, and ivy spun up the sides and the columns that made an arched walkway around the garden. There was a hedge garden with a fountain in the center, topped with a spritely cherub, and a pristine slice of pool that Lisa and I could swim in. I preferred the secret cove I so proudly discovered twenty minutes away from the manor and claimed. There were cliffs, and rocky shorelines, and pockets of woodland with running rivers, weeping willows, and dilapidated wooden bridges that might break under my weight. And I thought I knew it all like the back of my hand.

Lisa and I shared a room on the second floor. Our beds ran parallel to each other, against windows on opposite sides of the room, but we liked to push them together in the middle. We buried ourselves under a blanket tent at night with our flashlights, played with stuffed animals, and made up stories. We talked about what we were going to do the next day. We might have gone fishing with Grandad in the little wooden rowboat or helped Gran in the garden. I might have convinced Lisa to come with me on another exploration, this time to find animals to watch or somewhere to build a fort. We might have stayed inside and played board games or make-believe. Mother and Father didn’t like us watching TV, but we made a habit of sneaking into the living room when they were out. We were never bored. Lisa read and played piano. I painted and danced to the old records tucked away in the drawing room.

As we got older, we helped around the house more and explored less. We invited friends and boyfriends to stay with us for a few weeks, because each other and nature stopped being sufficient company. We worried about school, and money, and love. We abandoned the blanket tent, but we didn’t abandon each other.

One summer burns especially bright in my memory. Lisa was getting ready for Yale.

“Best school outside of Oxford,” said Grandad.

“Yes, we’re all so proud of you,” said Father. He never forgot to sing his daughter’s praise.

“You’re going to do brilliantly there, love,” said Gran.

“You ought to meet a fine university man, too,” said Grandad, with a wink.

“From a fine family,” added Gran.

“Indeed,” said Grandad, lifting his glass of gin to Bridget. “Let us know when you find him, ‘ey? He ought to spend a summer here before I die.”

I looked up from drawing shapes in the condensation of my glass of sparkling cider to see her face. She looked at me, too. I grinned and raised my eyebrows. She rolled her eyes and lifted her champagne glass to the group.

“Of course, Grandad. But I don’t imagine that will be happening any time soon—you’re far too stubborn for death.”

She spent day after day sorting through forms and making lists. When she wasn’t doing that, she was cooped up in the library with her face in a book, walking up and down the same strip of beach until sunset, or sitting on the edge of the pool and staring into nothing for hours, her feet just barely playing in the water. Gran and Grandad didn’t see this. Mother and Father didn’t, either. They saw the perfect, sensible, Ivy League-bound woman who woke up early every morning to help with breakfast and tend the garden, kept the books and piano keys warm, and was always smiling.

I caught her one night before dinner scrunched up in a fetal position on her bed. By the looks of it, that’s where she was all day as everyone assumed she was refining her skills. I turned on the light and she recoiled and turned to the wall.

“Lisa?” I said.

The only response was the rustling of blankets as she tightened her wraps.

The shades and curtains were closed, the tissue box empty, and I thought she could use a blanket tent. I turned off the lights and fit myself onto her bed, cradled against her. Her back shook as she started crying. I squeezed her arm and nestled my chin into the hollow above her collar bone.

“It’s too much pressure,” she said. “I can’t do it. They’re all fooling themselves.”

“I don’t believe you,” I said. “Lisa Hayward is great under pressure.”

“I don’t want to be Lisa Hayward, anymore! I want out. I want out of all of these big plans.”

I didn’t know what to say.

“Jesus, look at me. Telling you this… you’re only just starting high school. You don’t even have to think about the future yet.”

“I do, though,” I said. “They always make us think about the future.”

“Mom and Dad saw me at Yale before I could count,” Lisa said.

“You don’t think they saw me there, too?”

“Maybe, at the beginning. But you’re lucky, you’ve already crushed their hopes.”

“Wow, thanks,” I said. But, in her state, I couldn’t hold anything against her.

“I only mean,” she said, “you set yourself apart from it all, from the very beginning. You don’t have to get straight As or go to Yale or marry a nice man from an English family, or anything. You can do whatever the fuck you please.”

“Yeah, and they can look at me like the big, hopeless disappointment to our family.”

“I’d take that—”

“No, you wouldn’t,” I said.

“If you knew what it felt like to—”

“Stop it! You’re amazing at everything you do. You work hard and you have manners and you’re pretty and kind and smart. Trust me, I know, because I have to compare myself to you all the time. You’re going to do it, okay? You’re going to fulfill all of your dreams and their dreams.”

“But what if I can’t?!” She cried into the pillow. I hugged her and rubbed her back, nearly breaking into hysterics myself, and kept telling her she could and listing all the reasons I knew she could. When Gran knocked for dinner, I told her Lisa had caught some kind of stomach bug or food poisoning and I was going to stay with her for a while. Gran left in a worried ramble about all the gentle accusations she would lay on the chef, and whether or not the rest of the family would get sick.

What she didn’t realize is that the poison came from the inside, and they were sick with it already.

℘

“Sophia’s at Yale now?”

Bridget sat in the recliner across from me, her hands wrapped around a mug of coffee. My apartment wasn’t huge and was in the outdated style of the attached dorm, but it had all of the amenities I needed and I dressed it up as a home. Bridget had trekked there from across campus, and I let her use the back door.

“Yeah,” Bridget said. She laughed. “She was so embarrassed when she blurted that out.”

“I know,” I said. “I caught that.”

“So, how unsurprised are you?

“Completely. She had the Yale bone in her from the start.”

“They think I can get in,” Bridget said. “With the legacy, and Weston.”

“I bet you could,” I said.

“But I don’t want to go,” she said.

“Huh,” I said. “Do you know where you do want to go?”

“Not a clue. Someplace less… I don’t know…preppy, arrogant, expected?”

“Those are all good words to describe Yale,” I said. “Do you know what you want to do?”

“No,” she said. “Well, art. But I’m not supposed to do that.”

I brought my mug to my lips, trying to hide my grossly satisfied smirk. “I don’t believe in ‘supposed to,’” I said. “Be an elephant tadpole.”

Bridget stumbled over her sip of coffee. “What the hell is an elephant tadpole?”

I shook my head, “It’s nothing. I just mean you should follow whatever you’re drawn to.”

“Where did you go?”

“To college?”

“Yeah.”

“I went to Dartmouth for two years and then dropped out.”

“Why?”

“Why to which one, going or dropping out?”

“Both.”

“Well, I went to Dartmouth because it wasn’t Yale.”

Bridget laughed, “Makes perfect sense.”

“And,” I said, “I was in a really bad place, back then. I was feeling the pressure. I didn’t know who I was, or who I wanted to be, but I felt like everyone else was trying to decide for me. So, going to Dartmouth was almost a subconscious instinct to fight them. I didn’t go because I wanted to go, I went because it wasn’t what everyone else wanted. And that did more harm than good, because nothing felt worthwhile. I had something to prove, you know. If I was going to be different, I had to be good enough at whatever I chose to prove to them I was right about myself, right to make my own path. But I couldn’t figure out how to do that, and it really messed with me.”

“So you weren’t happy there?”

“No, not at all.”

“And didn’t they catch on? Didn’t they want you to be happy?”

“Well, they wanted me to be happy being what they wanted me to be. But I wasn’t, and that became impossible to ignore.”

I remembered the warning signs, and how it all began to unravel.

℘

I didn’t expect to care so much about Family Weekend. My family already had low expectations. They were going to think what they thought, and I was going to be who I was. But when I woke up that morning to a phone call from Lisa, letting me know that she, our parents and grandparents, and Samuel and Sophia were on their way, I was overcome by a sense of conviction to prove them wrong. I heard them yammering about me and Yale, all stuffed in the SUV together.

“Why would anyone take Hanover over New Haven,” grumbled Gran. “There’s absolutely nothing here.”

“Why would anyone take Dartmouth over Yale?” said Granddad.

“They’re all a bunch of tree-hugging, pot-smoking hippies,” said Gran.

“That’s why she’ll fit right in,” said Mother.

“Mom, come on,” said Lisa. “Don’t go into this in that state of mind.”

“Mommy, why are we here?” Sophia whined, “I’m hungry!”

“At least she didn’t decide to go to Brown,” said Father.

I dropped my old, mustard-colored telephone clumsily into its cradle and stumbled out of bed to study the sorry state of my room. My dirty laundry sat in a mountainous lump on my desk chair. The desk was cluttered with open books, my lipsticks and eyeshadows, and a stack of stolen mugs and utensils from the dining hall. A painting I had just started lay on a wrinkled sheet on the floor, paper cups and plates blotched with dried paint scattered about it. More drawers were open than not, and my Christmas lights hung halfway off the wall.

I had twenty minutes to get it in shape for my family. I stuffed the clothes into my closet, despite knowing my mother would open it to confirm her suspicions that I did exactly that. I tossed the dirty cups and plates into a garbage bag, leaned the canvas against a wall, and balled the paint-splattered sheet up. I played with the mess on my desk, but there were three knocks on the door before I could get it together. I glimpsed into the mirror, quietly feared for the collage of photos, magazine clippings, and album covers that filled the wall over my bed, realized I had forgot to make the bed, quickly stripped from my pajamas to jeans and a t-shirt, and slapped some deodorant on.

“Jody, open up, Sophia’s hungry,” said Lisa.

I tied my hair into a bun and swung the door open, which revealled the mass of well-dressed, blonde and white-haired relatives standing in the hall outside of my room.

“Aunt Jody!” Sophia broke her hand away from Lisa’s and hugged my waist.

“Hey, you!” I picked her up and twirled her around. “You’re hungry?” I blew raspberries into her stomach and she burst into giggles.

She nodded decisively and bit her tiny pink lip. “I said we should get snacks at the gas station, but Mommy said we were in a hurry,” she said.

“Is that so?”

“Uh-huh. We passed four gas stations,” she said, holding up four fingers. “Four! And Mommy said no. No, no, no, no, four times.”

I ran my fingers through her thin blonde hair, kissed her head, and lowered her. “How about some Oreos?” I moved for the snack box stashed under my bed.

Sophia grinned and nodded faster.

“No way,” said Lisa. “Nuh-uh. She hasn’t had a legitimate breakfast, we’re going to the dining hall.” Her stomach was so big and round with Bridget that I didn’t know how she fit through the dorm door.

“Okay,” I said, grabbing my key from somewhere in the desk chaos. “We can do that.”

Mother was scrutinizing my room with distaste and grumbling to Father about it. Grandad was crossing his arms over his Yale polo shirt as if to protect it from the surroundings. Gran was whispering in his ear and looking at me with sad, disappointed eyes.

“Your drawers are open,” said Mother. “And your bed isn’t made, why do you do this to yourself?”

I groaned. “It’s fine, Mother, I’ll fix it later. Are you all ready to go get food?”

“I’d like freshen up a little bit first,” said Gran. “Where is the ladies’ room?”

“Down the hall,” I said.

“Love, are you sure you want to use the loo here?” said Grandad.

“I have to do my business,” she whispered.

I shook my head in amusement. “Works the same as Yale, I promise.” I ushered them out of the room. “We’ll wait in the hall, okay?”

It was brunch that sucked the life out of me. Gran and Grandad pestering me about my future, Mother and Father marveling over Sophia and plans for the new baby, and Lisa basking in her own glow. After their campus tour, I sent them to a dance and music performance on campus and fled. I got up to go to the bathroom and found myself crouched against the stall with my arms locked around my knees and face swollen and on fire with tears. The world warped around me, and I couldn’t go back into the theater. I went outside, and the cool air felt nice, so I stayed there and walked along the sidewalk until I found a party and mooched off its alcohol. I had discovered sometime in high school that it made things better. Lisa had to pick me up outside of the frat house.

“What the hell were you thinking?” She clenched the steering wheel, her knuckles white. Her eyebrows looked permanently furrowed, and her cheeks were red hot. I thought her sheer rage might push Bridget right out of her.

I could barely keep my head from falling into the dashboard. “Nothing,” I slurred “Nothing—I was thinking nothing. I have no thoughts. No thoughts like your thoughts.”

“Christ, Jody, do you know how Mom and Dad felt when you never got back from the bathroom? To ditch us at your own damn school function, what the hell is that? Everyone’s safely at the hotel, in case you were wondering. Sophia is asleep, thank goodness. Give me that!”

She tried to pull the wine bottle from my grasp.

“You stole this?”

“No one owns it!” I said. “Let go!”

“Damnit, give me the bottle.”

“No! You’ll kill the baby!’

“I’m not going to drink it!” she said.

But she must’ve given up, because I woke up with the empty bottle next to my bed. I had apparently blacked out sometime shortly after she got me back into my room. She found me in the morning and suggested everyone else go explore the area with Sophia as she stayed with me until I could take care of myself. The flaw in the plan was that I wouldn’t be able to take care of myself for a long, long time. So as soon as I was up and drinking water, and able to process the tirade she threw at me, she made a run for it.

℘

“She should’ve been more sympathetic!” Bridget said. “She knew how hard it is, to give them what they want. She knew what the pressure feels like.”

“Yes,” I said. “But your mother made herself want what they wanted, too. And she never

got blackout drunk on Family Weekend.”

“So? People make mistakes!”

I shook my head. “Thank you, Bea. But there are some things that can’t be forgiven.”

“College kids get drunk all the time,” said Bridget.

“It wasn’t like that for me, though,” I said. Something sour built up in my throat. “It was

the first phase of what became a very serious problem.”

“I still think she should’ve been more supportive,” said Bridget.

“I appreciate that.”

“Okay, go on.”

“The incidents only got worse from there. I was spiraling down. So, I left Dartmouth. And then I went back, much later, to finish up. Then to Oxford for grad school—that’s where I picked up the accent. After spending so many summers in England, it wasn’t much of a jump. But it felt like something new, you know, to be a part of a new me.”

“I can understand that,” Bridget said. She furrowed her brow, apparently fitting pieces together in her head. “But, after you dropped out… what’d you do?”

“First? I changed my name,” I said.

“Why?”

“I changed from Joan to Jody in something like middle school, just because I liked it better. Felt more like me,” I said. I took another sip, imagining the next part of the conversation. “You know your mom’s maiden name, right?”

“Hayward.”

“Do you know what it means?”

She shook her head.

“Protector of an enclosed forest,” I said. “And, well, I didn’t want to be in the forest.”

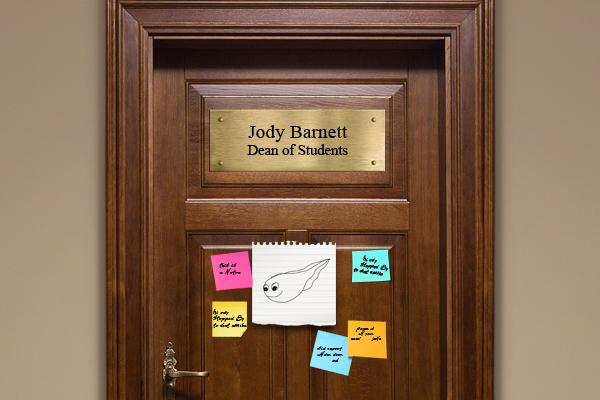

“So, what does Barnett mean, then?”

“Cleared after burning.”

“Clever,” Bridget said. “Okay, after the name change. Then what?”

“Then,” I said, “I got lost.”

℘

The decision came to me over a campfire where I sat with a group of friendly strangers. We roasted marshmallows, drank beer, and smoked weed. I was on a camping trip with the outdoors club and I realized how much I resented returning to campus. Aiden’s plan was certain bait.

Triangles of firelight flicked across his stubbly face as he shared his idea with us. He wore distressed carpenter jeans and an open button-down shirt, complete with a beaded necklace that fell past his chest. His voice boomed over the group’s chatter, mellow and confident. His hands made smooth gestures with his words. It was as if with every motion, they were peeling back layers of my skin and freeing me. I wondered if anyone else felt like he was speaking directly to them and his eyes were flickering exclusively for theirs.

“So, yeah,” he said, “I figured, what am I wasting my time for? I’m done with academia. I’m checking out. I’m going to travel; do some quality soul searching. Get myself some genuine life experience—everyone’s caught up with the wrong kind of stuff, here, you know? I’m not about that and I’m not trying to force anything anymore.”

He smiled at me across the fire. “I’ll do Europe, first. I’m going to hike the tallest mountains in Scandinavia, work on farms, see the Aurora Borealis, walk the old town squares, stay at hostels, visit pubs. Probably head through Asia too, and then the Rocky Mountains and up the Pacific Crest. Then into South America—I’m going to do it all. I’m not going to miss out on anything.”

“How are you going to finance this grand adventure?”

“I’ll book venues along the way. Sell my woodwork on the side. And a lot of places will let me work for my keep, too. I’ll figure it out as I go.”

“So, you’re going to be a nomadic hippy.”

“That’s the idea,” he said. “I’ve got some people to come along, too.”

“Oh, so a nomadic hippie cult leader.”

“We’re not meant to settle down,” he said. “We’re boxing ourselves out of so much of the world.”

“How high are you, brother? You’re going postal.”

He released a cloud of smoke and passed the bong along the circle. “Say what you want.”

I lingered as the crowd dissipated into their respective tents and considered where my strings were. I realized there was only one I would struggle to cut: the one connecting me to Lisa and little Sophia. But my family would disown me no matter what I did. I thought I might as well do it first. I started to imagine the process. I’d call them once to tell them I was leaving school and they should close my access to the bank account. Then I’d get rid of my flip phone, any unessential belongings, and my name.

“What’s on your mind?” Aiden appeared abruptly at my side. He was the only one, besides me, who hadn’t gone to sleep. He smelled like weed, sweat, and basil.

I looked up at him through the mess of blonde hair that had escaped my bun. The words came out like the sudden burst of rain at the start of a thunderstorm. “I want to come with you.”

He smiled. A toothy, knowing smile. “Okay.”

I furrowed my brow. “That’s it?”

He took my hand and stood up. “Come with me.”

“No, I meant—”

“I know what you meant. Come on, let’s talk about it.”

“Where?”

He smiled, again. He had a habit of doing that. “That’s the point,” he said. “The fire’s dying, the stars are out. I’ll fight off the bears.”

℘

Nothing could prepare me for finding Bridget that night, hours after curfew, as I was doing rounds to catch delinquents and hormonal couples. I walked along the grounds, which were lit only by the occasional lamp, the trails of light along the cobblestone steps, and the golden glow that emanated from the quaint white chapel and big brick dorms. The light just licked the tips of the perfectly groomed grass filling every space between the paths and buildings. It was my favorite time on campus. Everything was quiet, even the expanses of sports fields on the outer edge, and the sky was peppered with almost as many stars as the sky over Gran and Grandad’s house.

Bridget was alone, crouched against the back wall of her dorm, face swollen from crying. It was all too familiar. “Bea,” I said, “is that you?” I hugged my sweater closer to my body and lit her with my flashlight.

She tensed and considered evasion for a moment, but then shaded her eyes with her hand and looked at me. She said nothing. She dropped her arms back to her knees and squeezed herself.

“Bea,” I said, moving towards her. “What are you doing? It’s past 1 AM. How did you even get out here?”

“I went out the back door, from the basement. I couldn’t sleep… so I came out here to call my friend Rikki, because I didn’t want to wake anyone with the call, and she’s generally who I go to for these things. But she had to go, and then I just… I don’t know. I, uh, lost it. I couldn’t go back.”

“Bea,” I said. I felt foolish. I couldn’t commit to a strategy. “You’re really not supposed to be out here.”

“I know,” she said. “I’m sorry, I was bound to fuck this up sometime.”

“Shit, Bea.” I had to look away from her. “If it had been anyone else who found you…”

She watched me, trembled, and waited for a decision. Shadows dug into her face.

“Come,” I said, finally. I reached down to help her. As soon as she got to her feet, I wrapped her in a hug. “You can spend the night in my apartment. Sleep, if you can. I’ll stay up with you if you can’t. You’ll make it to Morning Assembly and you can tell people you were in the Health Center.”

When we got there, I set her up on the couch with a blanket and brought her a cup of herbal tea. I sat down next to her with my own cup.

“It’s supposed to help you relax,” I said.

“Does it work?”

“Um.” I laughed weakly at the half-empty box on my counter. “I don’t know, but it helps to believe it does.”

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“You should stop saying that.”

“This was supposed to go away. I was supposed to be okay here. No more insomnia, no more panic attacks. After all the shit, I came here to be better.”

“Sorry, girl,” I said. “That’s genetics for you.”

She gave me a questioning look and I tightened my grip on the mug. “Your mom’s is depression and OCD. Mine is anxiety and addiction. I don’t know what mix you’ve got—but it sucks, either way.”

She looked bewildered. “I didn’t know that.”

“She never wanted you to,” I said.

“But I always thought it was just me.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “Did you ever get diagnosed?”

“Only recently. PTSD, depression, and anxiety,” she said. She laughed at herself. “I’m a fucking nutcase.”

I squeezed her hand and decided to tell her how everything fell apart.

℘

Coming Friday, July 13: the conclusion of “Elephant Tadpoles.”

Victoria Merkle, also known as Tori, is a rising junior at Wellesley College studying English and creative writing. She lives in Brighton and interns with the Independent Publishers of New England. Now twenty years old, she has been passionate about writing since receiving her first creative prompt in the first grade.