Editor’s Note: Here’s the conclusion to Tori’s novella, a work which Fictional Café is quite proud to have premiered.

Elephant Tadpoles

by

Tori Merkle

Part III

It was amazing, for a while. There was a new adventure every day in with my gallivanting group of unchained artists. We bounced from place to place, absorbing each one and carrying its thumbprint to the next. I was pursuing my art. I was in love. I was free of rules and expectations. I was being who I wanted to be.

After the first year and a half, the need for a stable income settled in. Our savings were nearly gone, put into food and camping equipment and art supplies. Aiden couldn’t find a venue for his music. I couldn’t sell my paintings. We ran out of money to travel and desperately needed a breather, but had no desire or means to take one. We were also short on inspiration, alcohol, and weed: the three pillars of our existence.

One of the guys got us a trailer from some distant cousin of his. We parked it in the outskirts of London and the five of us lived there for a while. But as the situation got tighter, our friendships were strained under its pressure. Five turned into three, and three to two. We lived primarily on a boat in Hackney. Lack of work opportunities foiled that, too. And then we crossed a line.

“Babe,” said Aiden. “Listen, we have to get a train to London.”

I looked at him with such utter puzzlement that I thought my face would never collect itself.

“Jo, this is all we can do.”

“What miraculous cure is waiting for us in London?”

“We’re going to get an apartment.”

“With what money?”

“I have a plan.”

“Aiden, don’t you fucking tell me you’re going to cross that line.”

“Drugs sell, Jo. We need money, and I’m going to get it. We’re going to get an apartment, get back on our feet. We’ll make it work this time.”

“No, Aiden,” I said. “We won’t.”

He headed off sometime between midnight and sunrise, after I had thoroughly convinced him I wasn’t coming with him. He left me a can of coins. I lay awake all through the night. In the morning, I shoved a granola bar down my throat, scooped up the coins and a bottle of cheap wine, and found a phone booth.

“Lisa, it’s me.”

“Jody,” she said. I nearly lost it at the sound of her voice.

“Listen,” I said. “I’m in Hackney, England. I need you.”

“Do you, now?”

“Lisa, please. Things are really bad for me, right now. I don’t have any other options.”

“You’re tripping over your tongue. Are you drunk?”

I sobbed. “I’m a lot of things, Lisa.”

I heard her sigh. “Can you get to an airport?”

“I don’t think so,” I said.

“Christ, Jody—what do you expect me to do?”

I didn’t know.

“Okay, Grandad’s old friend—Uncle Franklin. He’s ancient, but I think he and his family are still in London. I’ll make some calls.”

℘

I thought about them a lot during rehab. I kept a framed collage that Sophia made me when she was nine on the white nightstand next to my white bed.

“Who are those precious little ones?” my roommate Anna asked. She was a frazzled woman, 58. She was an alcoholic. Her son and daughter stopped calling her a few Christmases ago. Then she had a breakdown after her husband’s death, and they tossed her into rehab. “Yours?”

“No,” I said. “My sister’s. Their names are Bridget and Sophia.”

“They’re beautiful.”

“Yes, they are.”

“Do they visit?”

“No,” I said. “They don’t.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Me too,” I said.

℘

Group therapy reminded me a little bit of sitting around the campfire with the outdoors club at Dartmouth. Everyone hated the world, described where things went wrong for them, and proposed useless solutions that got each other excited. The only difference was that people were less open without the help of the drugs and alcohol. And instead of marshmallows we had apple juice and stale cookies.

“So, I have to be good enough for her, you know?” Bryan said. He was longing for his ex-wife, again. He was the second-messiest crier, outdone only by Susan. “I’ll never forgive myself for that night. I used to blame the alcohol, you know. It wasn’t me, it was the alcohol. But I am the alcohol, you know?”

People mumbled and nodded and rubbed his shoulder.

“You’ve taken some important first steps, Bryan,” said Dr. Livingston. “You need to take responsibility for yourself before you make any kind of change. And then, figure out who you’re changing for.”

℘

Footsteps clumped down the stairs and pattered down the hall. Two blonde heads rounded the corner, one quicker than the other. Their mother shuffled behind them.

“Did you do all your homework last night?”

“Yes, mom. And I checked Bridget’s, too.”

“Thank you, love.”

I perked up, turned away from the stove, and braced myself for the welcome hug.

“Aunt Jody!” Bridget came in first. I scooped her up and spun her in circles.

“Good morning, monkey!” I kissed her cheek and tickled her stomach.

“Pancakes!” Bridget squirmed away and admired the cooking pancakes.

I swirled the pan around to keep the batter loose. “You got it! I thought it’d be a nice breakfast treat before school.”

“But we don’t really have time for that,” said Sophia.

“Good morning, sleeping beauty,” I said, hugging her and stroking her hair. “We’ll have time, I promise.” I looked to Lisa. She was watching with caution. “Samuel just left,” I said.

“I know,” Lisa said. “I saw him upstairs.” She filled the kettle for tea.

“Oh, good,” I said. Tiny bubbles formed and burst on the surface of the pancake. “You see—look at that, first one is already almost done!”

“I call it’s mine!” said Bridget.

“Oh, wait!” I scurried over to the cabinet and pulled out a bag of chocolate chips. “Can’t forget the most important part!”

“Hey, wait,” said Lisa, “those are for special occasions—”

I paused just before dropping a pile of chocolate chips on the pancake. “Seriously? Your chocolate chips are reserved? For what?”

“Christmas cookies, birthdays, dinner parties—”

“All right, well—who says this morning can’t be a special occasion?”

“Yeah,” said Bridget, “why can’t it!?”

“We’ll only use a few,” I said. “How about, say, what’s the magic number… six? One for each year of your life?”

“Yeah!”

“How about it, Mommy,” I said, “can you spare six chocolate chips?”

“Fine,” said Lisa. “I suppose—”

“But I want some too,” said Sophia.

“Alright, same rule applies—”

“That’s no fair,” said Bridget, “that means she gets more!”

“All is fair in love and war, babe,” I said.

Sophia cocked her head. “But we’re not at—”

“Okay!” said Lisa. “You can have as many chocolate chips as you want. Just eat up and get your teeth brushed.”

After they had left, Lisa set her full cup of tea on the counter. “Tea?” she asked.

I wrinkled my nose.

“Forget it.”

“Sure,” I said. “I’ll have some.”

She rose an eyebrow, but prepared me a cup anyway and sat on the stool across from mine. “Um, so—”

“Are you actually mad about the chocolate chips?” I said.

“No,” she shook her head. “It’s not that.”

I lowered my gaze and rolled bits of pancake around on the plate. She seemed to have sworn to herself she wouldn’t look away from me.

“Thank you, for being so good with the girls. But, Jody. You promised us, when we let you stay here, you were going to clean yourself up and go back to school to finish your degree. And now that you’re out of rehab, I mean, don’t you think it’s time? The semester has already started, and Dad pulled a lot of strings to get you back into Dartmouth. You have to finish there before you go to grad school.” She moved to the sink and began washing the dishes I had dirtied. “Assuming you get into one,” she added.

“Yes,” I said, finally. “I know, it is time. I’m going, next week.”

“Oh,” she said. “That’s great.”

“And then I’m going to grad school, and getting a job. I’m going to do everything right.”

“Great.”

℘

As I draped an extra blanket over Bridget, who had fallen asleep on my couch, I wished I could have done exactly what I had told Lisa I would. Instead, I let everything slip through my fingers.

I spent a long time pinpointing the mistakes. I couldn’t stop painting, or drinking. I forgot Lisa’s birthday and anniversary. I got arrested for possessing marijuana. I didn’t get arrested for stealing the Easy Bake Oven I gave Bridget on her eighth birthday. I didn’t help Lisa and our mother sort through our late father’s possessions. I didn’t go to his funeral.

Then there was the day that sent it all over the edge.

It was an elaborate plan. Committed to babysitting for the day, I ushered them into my car and drove. After frequent repetitions of “are we there yet?” we crossed the George Washington Bridge and I finally announced that we were.

Bridget marveled at the Hudson River and the towering skyline.

“New York?” said Sophia.

“Yes ma’am,” I said. “I understand you two have never been here.”

“No, we haven’t!” said Bridget, nose pressed against the car window.

Sophia also watched the passing scene in awe. “It’s so big.”

“Wait until we actually get in,” I said. “The city is… is sorta magical.”

“Does Mom know about this?” asked Sophia.

“Of course,” I said. “She gave me the okay. As long as we’re home before 11.”

“Wow,” said Bridget. “That’s later than normal bedtime.”

“I know, right? You’d think she’s lost her mind.”

“What are we going to do?” Sophia asked.

“Well, there’s my personal favorite—the M&M store. And then we’ve got all of Times Square to see. Maybe we can stop by the Empire State Building. And definitely Central Park, for sure. That’s a must.”

It was in Central Park, armed with bags of candy and cheap souvenirs, that I took a moment to listen to a street performer. A bearded man sang The Beatles’ “Let it Be,” strumming on a peeling acoustic guitar that stirred a precarious flow of memories.

“He’s pretty good,” said Sophia, at my side. “Should we give him something?”

“That’s a nice idea,” I said. I dug through my pocket. Sophia tossed a wrinkled dollar bill into his guitar case. I froze before I added my spare coins to the pile. “Where’s Bea?”

I looked around. Sophia looked around, too. I paced up and down the sidewalk. “Bea?!” In that moment, all of my progress was negligible. It didn’t matter that I had finished my bachelor’s degree and stopped myself from spiraling down into an abyss; I was still an irresponsible drunk. My insides froze up and hot sweat stung my neck. My heartbeat rose and my knees buckled.

“Oh, my god,” said Sophia. “Bridget!”

We wove in and out of the surrounding trees. The last I had seen her she was watching a squirrel. I assumed she was right behind us.

“Shit,” I mumbled under my breath. Panicking and searching was an impossible balance.

We walked up and down the park for hours, Sophia in tears. “I have to call Mom,” she said.

“No,” I said. “We’ll find her, I promise.”

“That’s not good enough!” she said. “What if she’s hurt—what if she got kidnapped! What if she’s in some creepy man’s cellar right now, eating stale bread!”

“Sophia,” I said, “I need you to stay calm.”

“How can I stay calm!”

“I don’t know!” I said. “But I’m already panicking, and I can’t have your panic on top of mine, or we’ll never find her!”

We found her at 11:15 PM, but not before I had let Sophia call Lisa.

“Bea!” I said. I ran towards her. She was hand in hand with a security officer outside of the zoo. He gave me a disapproving glance and handed her off to me. “What happened to you?”

“We found her!” Sophia spoke into her cellphone. “Mom? We found her, it’s okay—Bridget!” She hugged her.

“She was wandering through the zoo after hours,” said the officer.

“I didn’t know it was closed,” said Bridget. She started sobbing. “I lost you guys, and I couldn’t find you, and I didn’t know what to do so I just walked around, and I was so scared, and then I saw the zoo—And I went in, because I like the monkeys, and they were so nice—I didn’t want to leave.”

“Yes, she’s okay—Bea, Mom wants to talk to you.” Sophia handed Bridget the phone and Bridget held it to her ear with a quivering hand.

“Mommy?” She spoke through tears. “Mommy, yes, I’m okay. Yes, they found me.”

“She’s still on her way,” Sophia told me. “She’ll be here in five minutes, she wants us to wait for her at the park gate.”

I covered my face with my hands. “Okay.”

“Okay, I’ll see you. Yes, I’m okay. I promise. I love you too.” Bridget passed the phone back to Sophia and hugged me. “I was so scared.”

I picked her up and buried my face in her knotty hair. “I’m so sorry, love.”

“Okay,” Sophia said. “We’ll see you soon, Mom. Yes, of course, I’ll watch her.”

“I should talk to her,” I said, extending my hand to accept the phone.

“Okay, I know,” Sophia said into the phone, eyeing me. The more she spoke, the colder her glare got.

“Let me talk to her,” I said.

She waved my hand away in disgust. “She doesn’t want to talk to you—yes, Mom. Okay. We’ll see you soon,” she said. “Bye. Love you.”

“Shit,” I mumbled.

“Aunt Jody? Are you okay?” Bridget asked.

I shook my head, but told her I was fine.

℘

I spent that night in a bar. Lisa took the girls home and I was alone, the city feeling more ominous than magical. I could never forget what she said before she left. After the amount of times I replayed the confrontation in my head, it had a fixed, vivid place in my memory. It was the one thing the alcohol couldn’t wash away.

“Lisa,” I said, “you can’t not have anything to say to me.”

“Now is not the time, Jody.”

“Why not?” I said. “I’d rather you get it out.”

She laughed weakly. “Get it out? It’s not going anywhere, Jody.” She closed Bridget and Sophia into the car, telling Sophia she’d only be a minute, and approached me. “We’re done here. Understand? I don’t want you near my kids.”

“It was a fluke. I only looked away from her for a moment.”

“You’re seriously arguing with me, right now?”

“I just mean—as soon as I realized she was gone, I went into crisis mode. I wouldn’t have left the park without her.”

“And that makes it better?”

“No! I mean—I know I fucked up, but—”

“You know what, I fucked up too. I actually started thinking you were anything more than a degenerate addict.”

“I’m not—”

“Christ, the fact that I trusted you! The fact that I wanted you in their lives—in our lives! I thought, underneath it all, you were still my sister!”

“I am—”

“We’ve never been enough for you. Never. You always needed something more, or something different. You had to be a martyr. Miserable, and self-destructive. I can’t have that near my daughters—I can’t have them caught up in your chaos.”

“I’m going to school, Lisa, I’m getting clean.”

“I don’t care what the fuck you plan, or do, or claim to do. Your time is up, Jody. We’re done here. I never want to hear from you again.”

℘

“Do you remember that?” I asked Bridget.

“Sort of,” she said, “a little bit. I remember being scared, but I didn’t blame you. I never realized that was it, the thing that pushed Mom over the edge.”

“Yup.”

“But it was so long ago,” said Bridget. She sat in her usual chair in my apartment, and ate a pack of Oreos.

“It wasn’t just the one thing, Bea. It was a buildup. That was just the straw that broke the camel’s back,” I said. “Only I’m the camel, and I put the straw on my own damn back.”

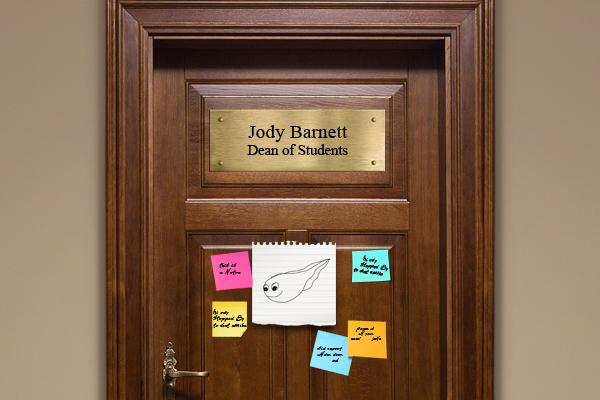

“Doesn’t make a difference,” she said. “You’re better now. You followed through, didn’t you? You finished school, you got clean, you became the dean of a damn prep school.:”

“Yes,” I said. “I did. I did another round of rehab and started going to AA meetings. I tried harder.”

“And it worked, this time?

“Loneliness is a good motivator,” I said. “I had lost everything. My sister, my nieces, my parents, everyone that ever cared about me. I couldn’t stop replaying that day in my head.”

“You didn’t lose me,” said Bridget. “I missed you.”

“You were too young to do anything but miss me.”

“How did you find Weston?” she asked.

“After I got my bachelor’s, I figured out what I wanted to do. I wanted to be in education, because I wanted to stop the cycle. Kids feel too much pressure. They need to feel comfortable being who they are and chasing what they want. So, I got a temporary job as an art teacher in a public school. And it was amazing. I felt like I had an impact, like I could reach these kids and help them embrace themselves. But I wanted to go bigger, reach more kids. So, I went to grad school, and then landed a job as an Assistant Dean in a private school. That lead me to Weston, and I somehow managed to pull it off.”

“And you’re happy here?”

“Yes,” I said. “In my twenties, if you told me I could be happy in a place like this, I’d have laughed in your face. But here I am.”

“I’m glad you’re here,” said Bridget. “Because I’m sure this place would suck without you.”

“Your mom would disagree,” I said.

She frowned. “She can’t resent you forever.”

“She can,” I said. “And she will.”

“No,” Bridget said. “She has to forgive. And I mean, come on—she’s no saint. All throughout high school and college? She wasn’t there for you. She let you fall apart. She made you feel alone. You have to forgive, too. You have to move on, and not as in move on from each other—You have to move forward. You need each other.”

“I don’t think that’s an option, love.”

“It is,” she said. “Take me as proof—she wouldn’t have brought me here if there wasn’t a chance.”

“She’s pretty desperate,” I said.

“So? Where does she turn to in desperation? You. They could’ve sent me to any old boarding school. But she needed you. She needed you, because I needed you—you’re important, Aunt Jody. We need you in this family.”

“Bea, I don’t think—”

“Okay, I’m missing something here. What the fuck is stopping you?”

“There are just so many things left unsaid.”

“Fine,” Bridget said, “if that’s all it is.” She set the Oreos down and pulled her phone from her pocket. She dialed and passed it to me. “Then say them.”

℘

Victoria Merkle, also known as Tori, is a rising junior at Wellesley College studying English and creative writing. She lives in Brighton and interns with the Independent Publishers of New England. Now twenty years old, she has been passionate about writing since receiving her first creative prompt in the first grade. “Elephant Tadpoles” is her first published fiction, but we are certain it will not be her last. Click here to visit Tori’s website.