As we continue to celebrate National Poetry Month, Here is Part 3 of Michal Larrain’s epic poem.

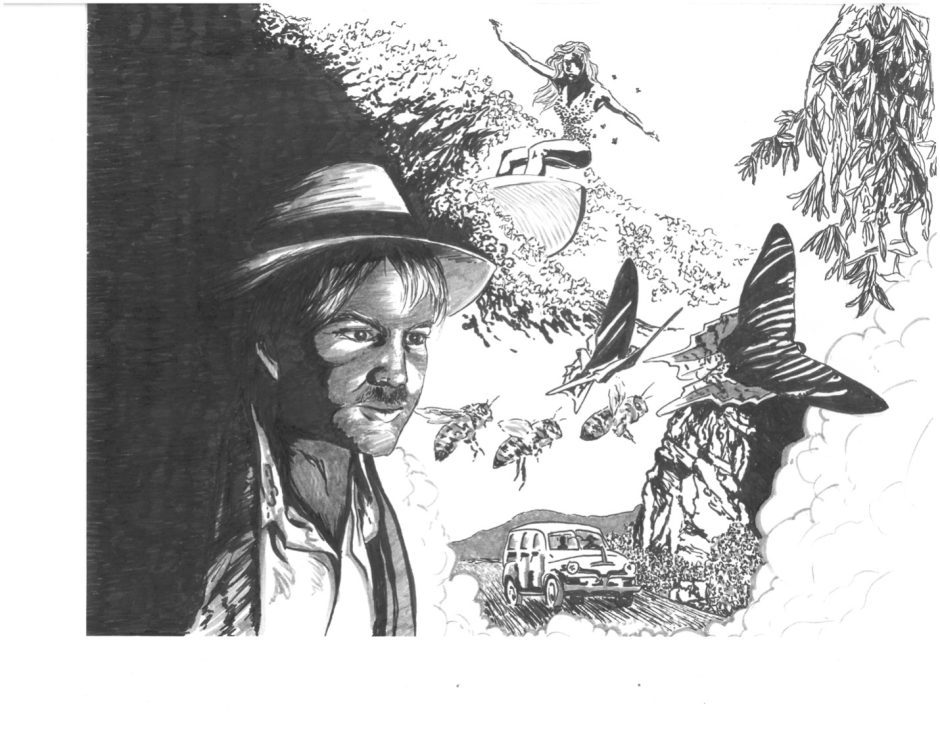

Thanks to those who have shared Comments – the author and your editors would love to hear what you think! This new episode, in our opinion, is a real doozy – and so is Katherine Willmore’s exclusive, exemplary artistic rendering. Watch for it!

The Life of A Private Eye

A Noirvelette in Verse

By

Michael Larrain

Part 3: The Spider Pool

She had trained enormous Amazonian butterflies,

each the size of a man’s hand,

to land upon her person in a pattern

either random or preordained,

and stay there for a space of hours,

forming a living evening gown,

their wings slowly fanning,

black and green bands of breathing velvet.

Speculation was running rampant as to her technique.

A solution of pollen and honey holding them in place?

Inter-species telepathy? Good vibes? No one could say.

It was Halloween for eye-candy around the pool,

starlets, models, actresses of considerable reputation,

trophy wives on the arms of powerful producers.

But they were all extras on this set, a backdrop for Jade Bellinger.

Even the other professional glamour-pusses, present in the hope

of becoming the center of attention, couldn’t tear their eyes off her.

As a final proof of her allure, jealous wives, instead of glaring at

their wonderstruck husbands, had chosen to concentrate their own gazes

on the woman in butterfly couture. As for me, I turned into a bright lad,

who, instead of a cowboy or a fireman,

wanted to be a lepidopterist when he grew up.

“Hello. I’m Jade.”

“You must have been named after your eyes.”

It was gracious, though hardly necessary, for her to introduce herself.

She was the toast of Hollywood as certain celebrated beauties

used to be known as “the Rage of Paris.” She carried a kind of

deep effortless glamor not seen since the days of Garbo and Dietrich.

She had turned down Vogue and Vanity Fair covers,

and chose not to pimp herself out on talk shows or social media.

Said to be the most elusive interview in town,

she wouldn’t even go out on promotional junkets for her own films.

“You may be wondering why you were invited,” she said.

“Hmm?” Hundreds of slowly waving antennae had captured my attention.

“I’ll bet you get great reception in that dress,” I said finally,

because private eyes are expected to trade in wisecracks.

It was a wrap party for her new movie, Seeds of Doubt,

held at her home high in the Hollywood Hills.

“Are you familiar with the history of this place? she asked.

“I know the legend, the rumors, nothing in particular.

Didn’t it used to be known as the ‘Spider Pool’?”

“Yes, in the fifties and early sixties. Before that, in 1923, a very eccentric

silent movie director named Jack McDermott bought this property

and built a deeply peculiar house here. While working, he had

noticed that film sets, which must have been much sturdier in his day,

were routinely discarded. So he decided, rather than consigning

them to the flames, to construct his home of them. He used pieces

from Song of Love, The Thief of Bagdad, Robin Hood,

The Phantom of the Opera. He ended up with a crib that was

weird even by Hollywood standards, a sort of Moroccan-Egyptian-Navajo

palace, all hauled up the hill by donkeys. Minarets, secret passageways,

a mock-cemetery, an upside-down room with the furniture attached to the

ceiling and a chandelier to the floor. Inebriated guests who had passed

out the night before would awaken there with such strange hangovers I expect

many of them swore off strong drink on the spot. He even had a cannon

from “The Sea Hawk” mounted on his roof. He died in 1946

of an overdose of sleeping pills and the house burned down the

following year, possibly torched by squatters. Shortly after his passing,

the house’s second generation of notoriety was inaugurated. The grounds

became a kind of ‘cheesecake factory’ where both amateur and professional

photographers took to snapping pics of nude pin-up models around the pool.

One of the photographers was Harold Lloyd, ranked by most critics

as a distant third among silent screen comedians behind Chaplin

and Buster Keaton. Lloyd led a curiously divided life, devoted on

both sides of it to photography. At the Beverly Hills manse known

as Greenacres, where he lived with his wife, the actress Mildred Davis

and their daughter, he took respectable portraits of the movie folks of the day.

But at the Spider Pool, it was the nude models he was drawn to.”

I couldn’t help wondering why she was giving me such elaborate

background on her house. “Is that why you bought the place?” I asked.

“Because you were fascinated by its history?”

“Partly,” she said, “I thought it would be fun to

broker a marriage between old and new Hollywood.

But mostly because I wanted to design and build a house from scratch.

The views are superb and my nearest neighbor is a half a mile away.”

If you don’t count the helicopters, I thought, glancing skyward.

“Ah, yes,” she said. “The gutter press have gone up in the world.

At the moment they’re covering the party,

ordinarily, they swoop in trying to catch me with my top off while sunbathing.

If I hold up a sign saying ‘CHIPS!’, they’ll drop bags of

Doritos. Once I tried for guacamole, but things got rather messy.”

She took a deep breath. “But there’s another, less well

known aspect of the Spider Pool,” she went on.

“In 1957, one of the models was found floating face-down in the pool.

It was ruled an accidental death, due to intoxication, even as

rumors persisted that the girl had been Harold Lloyd’s mistress.

But the investigator who had been first on the scene

never fully accepted the official explanation and had kept digging.

He was able to produce evidence indicating that, despite the amount

of alcohol in her blood stream and the water found in the girl’s lungs,

she had died, or been dispatched, elsewhere

and her body moved to the pool afterwards.

His suspicions fell first on Lloyd and afterwards on Lloyd’s wife.

At that point, he was called to heel. Ancient history, I know.

But recently, a second death by drowning occurred here.

Another young women, a close friend of mine,

was found in the middle of the night,

also nude and face-down, also drowned,

also ruled an accidental death, and this

time the case was hushed up even harder.

Studios have a frightening amount of pull in this town.”

I waited, nearly certain of what she would say next.

“I think my friend was killed.”

“Is that why you want to hire me?”

“Yes. You see, the police passed it off as routine, dismissed

it out of hand. It’s even possible that I was the intended victim.

My late friend, before she landed her first speaking role,

had on occasion been my body-double in a few nude love scenes.

She bore a faint resemblance to me facially,

but from the neck down, we were virtually identical.”

I considered asking for the titles of those movies and thought better of it.

“These events so eerily mirror those of 1957 that I can’t help

thinking that the killer, if there is one, is working from a script.

But since the previous case was slammed shut,

I can’t discover what happened then,

and so I can’t learn what might happen now

in parallel to the earlier eras crimes.”

“Doesn’t sound like a murder mystery to me,” I said.

“More like one of those cheesy horror movies where the cheerleader

with the largest breasts is always the first to be killed.”

She cast a bemused glance at her assembled female guests,

most of whose bosoms had been so spectacularly enhanced

that their feet were forever protected from the threat of sunburn.

“In that case, I would appear to be in no immediate danger,”

she said with a droll grin.

“But why hire me? This town is crawling with

agencies with far greater resources and manpower.”

She looked at me for a long time and then looked away.

“Your father was the lead investigator into the murder allegations in 1957.

When he began to invoke the names of celebrity suspects,

a minor sensation ensued, but then pressure came down, with prejudice.

Without the chance to mount any kind of defense on his own behalf,

he was branded a ranting drunk, a publicity hound, and suspended indefinitely.

He was pilloried by the press, accused of

grandstanding and became a laughingstock.

The case was never solved, was covered up thereafter,

and your father never worked in law enforcement again.

No one knows what became of him.”

God knows I didn’t. I knew only

that I had known him too little, and after my thirteenth

birthday not at all. He had taken to an armchair in front

of the television, then taken to drink and finally to the road.

This was rather embarrassing. The client knew more about

the detective’s father than the sleuth himself. Whenever I had

asked about my dad, my mother had pointedly changed the subject.

“Some of the models are still alive,” Jade continued.

“And their reputations are thriving, thanks to the internet.

They might enjoy sharing tales of their youthful indiscretions with you.”

“I wouldn’t mind it myself,” I said.

As it happened, I knew all their names by heart.

One of my happiest childhood memories was sitting

in my boyhood tree-fort dealing out hands of solitaire

for games I never played, preferring instead to study the backs

of the cards, which featured the models of the Spider Pool:

Eve Eden, Donna “Busty” Brown, Bobbie Reynolds, Dixie Evans,

Diane Webber, Eleanor Ames, Donna Watkins, Delores Del Monte,

Wilhelmina Barrenfen, and the fabulously,

if improbably named Tura Satana, who, along with

Miss Evans, was known to have posed for Harold Lloyd.

My dad must have confiscated the cards in a raid,

tossed them in the drawer where I came upon them,

and either forgotten about them or decided

to humor his young son. I would stare at them for hours at a time,

reverently whispering the women’s names

as an adolescent’s erotic rosary. Once, I made so bold

as to attach a half-dozen or so to the spokes of my

Huffy bike with clothespins and ride out around the town

with a great secret in my possession,

the snapping of the cards as cool as Maynard G. Krebs.

**

In the earlier era, the spider who gave the place its name

was a huge blue tarantula in a tile mosaic

on a retaining wall facing the pool.

Currently, the entire bottom of the pool at Jade’s house

was a tile mural, at its center an even larger, elegantly rendered

black widow hulking over a nude woman trapped in its web.

I looked away from Jade long enough to notice

that a number of young women in bras and panties

had taken to diving in and kicking down to the drain

to retrieve liquor miniatures which they surfaced with,

knocking them back triumphantly,

shrieking and whipping their hair around.

I wondered how long it had been since I’d started to regard

nubile beauties in their undies as so many frolicsome children.

“So, who would you be equivalent to from the fifties original?”

I asked my hostess. “The director, maybe?” she said, ruefully.

“Well, I picked out the materials for the house, anyway.”

The dusting of freckles across her nose and breastbone

lent her an endearing air of the tomboy, while her hair,

a glowing auburn, consigned me to the flames.

Just as certain actresses can always find their key light,

Jade gave the impression of carrying her own patch of shade,

a coolness more alluring than the heat being generated by

the other women around us who seemed, in comparison,

to be working too hard at it, as though seducing on a deadline.

“The only reason I even know about your father,” she continued,

“is that I was friendly with a retired script supervisor who had

once been a police dispatcher. She was a little hazy on the details,

but remembered that the case had been buried,

with an emphatically closed casket, as it were.”

Looking at her, my eyelids turned into opium poppies

and I could feel dreams, my own and others’,

floating and filtering through my body,

editing me down into the director’s cut of myself,

the version of me too controversial ever to be released until this instant.

The moving wings of the butterflies seemed to be motioning

me closer and waving a simultaneous goodbye,

accounting no doubt for my apparent paralysis.

I wondered if she shivered all over when they lifted off,

and whether she summoned squadrons

of luna moths to serve as her nightgown.

“If you’re able to make any sense of this business,” she said,

“come back and we can meet privately. No helicopters.”

“OK. I’ll bring chips and guacamole.”

**

I must still be a P.I. I had a second floor home-office above

a rundown tiki bar on the seedy outskirts of Venice Beach.

I had a bottle of hooch in one of the two mini-fridges

upon which rested the weatherbeaten door that served as my desk.

And now, apparently, I had a client. A movie star, no less.

There was a bedraggled palm tree right outside the office window

which I’d been known to shinny down

to escape process servers and ex-girlfriends.

Right now it looked ready to lean against a lamppost for support.

The joint downstairs was frequented by a

lively assortment of disreputable characters:

neighborhood winos cadging either sunblock or a drink,

skateboarders, rollerbladers, beach-combers, volleyball bums.

The bartender was a Hawaiian tropic blonde so profusely illustrated

that her neck-to-ankle tattoos constituted a kind of de facto clothing.

Jade had fronted me a retainer large enough to pay my tab at the bar.

So, using the ancient dumbwaiter in the wall,

I sent down a drink order and tried to sort out my thoughts.

All in their mid to late eighties, the last of the Spider Pool girls,

reduced to four in number, had had no trouble talking about the old days,

though they seemed a bit bewildered by the present.

There should be a retirement home for old

pin-up models and burlycue queens, I thought,

A place with plump cushions and cabana boys,

where they could luxuriate in the recollection of the catcalls,

wolf whistles and glad excitement they had once inspired.

I decided to raise the subject with Jade.

I found all four of them in drab nursing homes,

one in Silver Lake, one in Echo Park, one in Sherman Oaks

and the last way the hell out in La Habra.

Each of them had framed photos of their younger selves in their heydays

proudly displayed at their bedsides, and each remembered the others,

though were unaware that their former colleagues

were still alive and a very few miles away.

Harold Lloyd they remembered as a perfect gentleman,

neither a lech nor overly impressed by his stature in the industry.

He had seemed more titillated by his expensive photographic

equipment than the naked women he had posed so decorously.

One of the old dolls, though he had never hit on her—

contenting himself with gallant flirtation and comic

pratfalls around the pool to keep the models amused—

recalled his flings with a few of the girls, passing fancies

known to his wife, who, according to a memoir written

by their granddaughter, had simply “looked the other way.”

It had been a different time, of course, one in which a

greater value had been placed on privacy. And Miss Davis

had had a good life, a palatial estate, and a family to protect.

Still, it gave me pause. Had jealous rage seethed beneath a placid exterior?

Had my father found a way to ruffle those calm waters?

The breeze off the ocean was as salty as ever, but somehow

more enticing, I sensed, just as a coconut grazed my forehead.

Why would the palm tree be drilling me with a high hard one?

I wondered, and looked to my left to see my client waving at me.

The tree was close enough to the window

that I was able to lean out and haul her in.

“You could have just taken the stairs,” I said,

“No one would have recognized you in that get-up.”

She was wearing white pedal-pushers, a crop-top t-shirt and flip-flops.

“Yes,” she said, sliding into character, “Sometimes I like

to walk among my subjects disguised as a commoner.”

Then, sliding out again, “What’s a girl have to do to get a drink in this dump?”

Fortunately, my order arrived in a timely fashion.

She was happy to share, and delighted by the dumbwaiter.

“I have a machete around here somewhere.”

I found it on the wall and chopped the coconut in two,

dividing the big Mai-Tai between the halves.

“I thought we were going to meet at your place.”

She snorted. “It’s staked out like the crime scene of the century,”

she said. “The paparazzi can always tell when something’s up.

I’d have had to bring you in through the tunnel.”

“You have a tunnel?” I said, incredulous.

“Sure. How do you think I got out? It’s not really my tunnel.

It came with the house, a last laugh from Jack McDermott.

I found it accidentally one day when I was hiding in the wine cellar.”

“Where does it go?” “Wouldn’t you like to know?” She stuck her tongue

out at me. “I keep a car service on stand-by to pick me up when I emerge

from my underground lair. But they’re sworn to secrecy.”

She was hoping for a progress report, but I didn’t have much to tell her.

Harold Lloyd and Mildred Davis had gone to their respective rewards.

My requests to interview his living relatives were politely, if frostily, declined.

The police files didn’t offer so much as a mysterious hole

where a missing folder might once have been. The case was simply closed.

I couldn’t even go over the grounds of the former Spider Pool,

unless I was prepared to excavate my own client’s property.

And none of the models remembered any investigation into a possible homicide.

Too bad. I’d been hoping to hear stories about my dad.

She had left by the stairs, disappointed by my report, but urging me to continue.

The low-life riff-raff in the club was so intent on their own dissolution,

they paid no heed to one of the most famous women on earth passing

through their midst. No wonder I thought them boon companions.

**

I was still sitting at my desk, about to send down for another drink, when word reached me of my mother’s death.

Though it had long been expected,

I was no readier for it than anyone ever is.

I made my final trip to the family home,

where she’d been living alone for more than thirty years.

After packing away her possessions and deciding on a few keepsakes —

the rest I thought I would donate to her favorite thrift stores—

on impulse, I hiked out into the back yard,

glad to find my old fort still standing

in the arms of its venerable walnut tree.

The trusty rope ladder seemed sturdy enough.

I tested it and found it would take my weight.

The fort was a boy’s notion of what his future bachelor pad might be.

Four knotholes high, with a telescope, a trap door

(and a second one on the ceiling serving as a rough skylight),

the piratical ladder, a mattress and a hammock,

I’d been ready for make-out parties, had I but known any girls.

The ones I imagined had sat in the hammock

in cotton skirts and lambswool sweaters,

their ankles demurely crossed while I lay on the bare mattress,

dazzling them with my mastery of card-shuffling

and snappy patter sure to melt a junior miss’s heart

and make her come across with a kiss.

Time and the elements had conspired to lend

the Antonio & Cleopatra cigar box I’d kept my precious

cards in the sun-faded look of the old Playboy magazines

I had stashed under the mattress. But the cards were still there,

and the intervening decades had done nothing to erode the charms

of the Spider Pool girls. The black and white shots

were as sharp as ever, and the models—pre-aerobics

and pre-silicone—had the same welcoming contours that

had led me to single-handedly deflower

myself in the very spot where now I sat.

I was both startled and delighted to find first-bloom portraits

of two of the now elderly ladies I had recently visited.

I tucked them into my shirt pocket to share with the photos’ subjects

at a surprise reunion I determined then and there to organize.

But the cigar box was fuller than it should have been,

filled almost to collapsing. It didn’t take me long to learn why.

When I set my collection aside, I found a stack of yellowing index cards.

On them, in scrawled handwriting I knew well from long-ago

Christmas and birthday cards, were my father’s case

notes about that night at the Spider Pool in 1957.

**

In pencil, he had created a maze of scribbles, cross-outs,

arrows, diagrams, rewrites, question marks, underlinings,

erasures, names I recognized and names that meant nothing to me.

I laid the cards out in what I thought was chronological order.

It would have been incomprehensible to anyone who hadn’t grown up,

like many a baseball-loving boy before him, practicing the forgery of his father’s signature

so he could stay home from school and watch important games.

So, in an odd way, it was sort of like reading my own writing.

Once I had a handle on his system, I was able to follow his surmises.

At first, he had thought the girl’s secret sugar, Harold Lloyd himself,

to be the killer. But a number of witnesses had testified

to his presence at the Spider Pool when the girl’s life ended

in another location, and his suspicions fell upon Mildred Davis.

He’d gone exhaustively over the phone records

of all the principle players and found a series of calls

initiated by the girlfriend to the wife. He’d been unable to find

a scrap of hard evidence proving that a confrontation had followed the calls,

but it seemed not unlikely. At that point, he’d been stymied. He believed

that Mildred had put up with a series of minor and meaningless

physical collisions between her husband and various young models,

but that this time Harold had fallen in love with one of the girls,

leaving Mildred’s whole life suddenly situated over a fault line.

Then he’d had been suspended and lost all official powers.

Without a badge, a gun or the backing of the department, he had

gone rogue, and become an unlicensed P.I., my ancestor in two respects.

When Mildred herself refused him an audience,

he’d waited for her staff to run errands and braced them

in markets and parking lots, perhaps giving the

impression that he was still on the city’s payroll.

Then he’d knocked on the doors of the Lloyd’s neighbors,

a few of whom actually gave him the time of day.

And when he was turned away, he laid small sums of money on

their maids, gardeners, pool cleaners, secretaries and chauffeurs.

Amazing how far a double sawbuck went in 1957.

A switchboard operator who owed him a favor,

\a mail carrier who’d been on his route at a fateful moment, linemen, milkmen,

dog-walkers, a delivery boy from a linen-cleaning service,

a Western Union telegrapher who played the ponies—

all helped him to painstakingly develop a picture

of events at Greenacres on the day and night of the murder.

When he was done, it all added up to an unsettling revelation:

He had been right about almost everything. The girl had

died at the Lloyd residence and her body moved

to the Spider Pool. And Harold Lloyd had been innocent

of any wrongdoing. And Mildred Davis was the key to the case.

But she hadn’t committed murder either.

There had never been a murder.

Instead, born of panic, there had been a cleverly conceived

midnight drama of misdirection, staged by Mildred’s lover,

the superintendent of the Beverly Hills Police Department.

**

Since my father was no longer on the force,

he hadn’t needed to worry about jurisdictional disputes

between his old station of the Hollywood Police

and their counterparts in Beverly Hills, whom most

members of the LAPD thought little more than fetch

and carry boys who truckled to the whims of the

wealthy citizens of that manicured fantasy land.

“Poodleguards” they’d called them.

But when he’d gone to his chief and aired

his suspicions regarding the superintendent,

his dismissal had been practically guaranteed.

The chief was a career man, and knew full well

how things worked in Southern California.

My father couldn’t make an arrest, and his “wild and irresponsible

accusations” only brought further ridicule down on his head.

He alone had woven the network of servants’ whispers into a coherent story.

Mildred, bored with waiting for her errant husband to return

from the beds of his hussies, had taken to attending charity functions

where she had met and caught the eye of the superintendent of police.

Their subsequent affair had filled her afternoons agreeably,

and since her charity work included many police fund-raisers,

his presence at the estate could be easily explained. She was

within her rights, she felt, to get back at her husband, but

had no desire to flaunt her own infidelity in his face.

When the calls started coming from the girl, who wanted to

speak to Harold’s missus in person, to convince her that in every

sense but the contractual her marriage was over and

a quiet divorce would be best for all concerned, Mildred had

refused to take them. Overcome by their sheer volume,

however, she eventually relented and agreed to a meeting,

if only to set the misguided girl straight. But her candor

had proven disarming. She was so guileless and so

clearly not a gold-digger, that Mildred had softened.

They sat together on a settee and spoke about Harold Lloyd.

Mildred still loved him, if only as her daughter’s doting father,

and the girl all but worshipped the silent screen star

who had become her clandestine lover.

A pitcher of gimlets later, the new friends decided to take a swim.

She loaned the girl a suit, changed into a

charming number she’d bought in Catalina,

and gone into her kitchen to make a fresh batch of gimlets.

By the time she walked out onto the patio to the edge of the pool,

half-sloshed herself, the girl was already a goner. Mildred had waded in,

but Harold’s young mistress would never be the life of anyone’s party again.

Now the lady of the house had a body on her hands and nowhere to turn,

no choice but to alert the police. Squad cars, sirens, scandal, ruin.

Terrified by repercussions that could mean the end of respectability,

maybe even the destruction of her family,

she tossed off another gimlet in a single gulp, and called her lover.

**

Once the superintendent had arrived and been acquainted

with the unfortunate details of the matter,

Mildred was able to breathe a great sigh of relief.

Rather than calling for a forensics team or an ambulance,

he had simply asked for the loan of a blanket.

Though she still had strong feelings for Harold—

the nominal head of her family—she wasn’t altogether opposed

to the idea of his being implicated in his girlfriend’s death,

provided no shadow were cast on herself or their daughter.

But it shouldn’t come to that, he assured her.

It wouldn’t be hard to make it look like an accident,

since that’s exactly what it had been. Neither of them needed alibis.

Once the presence of the body was established in the Hollywood Hills,

it was only necessary for them not to have been at the Spider Pool that night.

A thoughtful fellow, he had even dry cleaned and returned the blanket.

**

What was left for my father to do? Though a handful of models and

snap-shooters had been at Jack McDermott’s old place

on the night in question, none could corroborate his theory.

No one recalled a man pulling into the driveway and

moving a body from the trunk of his car to the pool

(Though the house was no longer standing, Harold Lloyd

and some of the other photographers kept the pool filled

and cleaned as an inducement to the shyer young ingénues

to shed their dresses along with their inhibitions). Probably

he had waited out of sight until the weary revelers had

decamped before depositing the dead girl’s body in the water.

But without a witness, my father had no clinching piece of evidence.

Had he tried taking his skein of loose threads before a state’s attorney

and demanding that an obstruction of justice charge be brought

against the superintendent, it would have been like

laying an enormous spider web out on moving water.

**

Here the case notes ended. It occurred to me that this

stack of cracked old index cards was my sole patrimony.

There was no separate letter explaining why he’d

stowed this record of his investigation in my tree-fort.

I could only think that he hadn’t wanted me to remember

him as the babbling monomaniac portrayed by the press.

He, too, must have made one last visit to the family home.

If he’d spent any time with my mother then, she’d never mentioned it.

And now I couldn’t ask her. Or him, for that matter. If he was still alive,

he’d be about fifteen years older than the Spider Pool models,

crowding the century mark. I had no idea of where he’d lived

in the latter years of his life, or where he might have died.

San Pedro? (He’d liked to fish, maybe he’d crewed for a commercial operation),

Skid Row? (he’d been a strict teetotaler until slandered as a lush,

but once he took to the stuff, there’d been no stopping him).

Some anonymous apartment in the valley?

I had never thought to look for him because he had left us.

To him, it must have felt like he’d been kicked out of the world.

**

The tiki bar had cycled through many names since it first opened.

When I’d moved into the office, it was called “Palm Bitch,”

then “The Ukelele Ladies Room,” “Gabby’s” (after Gabby Pahinui,

one of the fathers of slack key guitar), “The Moon & Sixpence,”

then for a couple of disastrous months it had been a Polynesian comedy club called “Aloha-Ha,” then “PL&HL”

(for Peace, Love and Hang Loose) before finally

settling into its current groove as “Be-Bop-a-Hula.”

I was able to remember all the names

because I had a complete set of cocktail napkins.

And because I was operating on Jade’s dime and had

been instructed to spare no expense, I went a little

luxury car crazy, renting four saloon-style1950s Bentleys,

one for each of the reunion’s guests of honor,

so they could arrive, one at a time, in classic rides from their

glory decade and make separate, red carpet-like entrances.

For wheel men, I hired four hunky would-be actors—tan, chiseled,

shirtless—with lots of white teeth and dark wavy hair.

I felt I owed it to them. Hadn’t they, albeit unknowingly,

given me a sort of reunion with my father? Jade had promised

to make an appearance, though she hadn’t shown up yet.

I wasn’t altogether comfortable about telling her what I’d uncovered.

Though if no murder had been committed in 1957,

shouldn’t her belief in a remake convince

her she had nothing to fear? I didn’t mind

coming off the payroll so much as the thought that

this could be my last time in her company.

She made a man, any man, feel he had a chance with her,

that he alone had been granted a glimpse of her innermost self:

assistant directors, the gofers on her movie sets, delivery boys,

even screenwriters. She was so far from seeming unobtainable

that an aging shamus might believe for

a moment that she had set her sights on him.

In a career spanning fewer than ten years,

she had already portrayed a remarkably diverse array of characters—

a prim governess, a lascivious countess, an Irish barmaid,

a Russian peasant, a concert violinist,

a schizophrenic barrister, a Prime Minister,

lost souls and women who ran the world

(sometimes at the same time)—

yet invested in all an erotic charge so powerful that at the end of her performances,

most men and not a few women were unable

to rise and leave the theater until the

violent trembling of their knees had subsided.

In person, the effect was even stronger.

Stepping out of their limos, the Spider Pool girls,

looking not in the least like doddering old ladies

as they waved to the small crowd of fans who

had shown up in response to my internet posting,

stopped to sign autographs and pose for photos before

entering the dimness of the club. Deanna came first.

I made a fuss over her and positioned her so that she

could see the door. Maggie came second, and when

she set eyes on her old colleague, threw her arms into

the air and did a credible runway strut over to our table.

Next came Karina, then Deborah Eileen “Dangerous Curves” Donegan,

the greetings growing ever more boisterous.

The last time they’d all been around the pool together,

getting caressed by lenses individually or in duos,

I had just entered junior high school, oftentimes with their cards

smuggled into my schoolbooks.

I never did pass geometry.

Most of the cocktail waitresses in the place wore whatever

outré ensembles they’d been cruising the boardwalk in.

But ours, when she showed up to take our drink orders,

had on the hokey old fake Hawaiiana stand-by of

grass skirt and coconut bra to go with her purple hair.

She improved on the idea, though,

by handing me a pair of clippers and telling me to feel

free to trim her skirt if I heard that hemlines were going up.

The Spider Pool girls spread a colorful assortment of medications

out on the table and took them with sips of their froufrou drinks.

They’d all come armed with a bewildering assortment

of meds, so more than a few rounds were called for.

Suddenly, Deborah Eileen trained her

grey almond eyes on me and declared,

“You remind me of someone, someone from the old days.”

Sipping reflectively. “He was some sort of law.”

“Not a vice cop, I hope.”

The cocktail seemed to jog her memory. “No, a dick.”

“Most of the men we met in those days were dicks,” said Karina.

“Not that kind of dick, dearie,” said Deborah Eileen. “I meant a detective.

C’mon, Maggie, you remember that cute police detective

who came sniffing around the pool, don’t you?

We kidded him unmercifully when he refused

to strip down to his skivvies and take a swim with us.”

“Oh, yes! He said he wasn’t allowed to skinny-dip while on duty.”

Maggie was Maggie Amberson, not only a Spider Pool girl,

but a minor luminary of local 50s burlesque who had recently

auctioned off pairs of her old pasties and tassels on E-Bay for

enough to pay her way in the nursing home for the remainder of her days.

“But you told me you had no recollection of a murder inquiry,” I said,

and then remembered that she hadn’t said that, had in fact said nothing

at all when I queried her on the subject. Now that I recalled our chats,

none of them had done more than shake their heads and quietly demur.

“I must have taken a little nap during your visit,” she said, coquettishly.

“I should have taken one too,” I said. “Then I could

have bragged that I’d slept with Maggie Amberson.”

“You’re a sweet boy,” she said, patting the back of my hand.

“Not so sweet as all that,” I thought, recalling the fantasies

I’d once had of her becoming my “French tutor” in the tree-fort

and introducing me to the mysteries of love surrounded by birdsong.

Once the latches on their memories had been loosened by the drinks,

the prescription drugs, the fun of the reunion, and the Half-Cuban,

half-Hawaiian house band, Swing a Dead Cat, they began

trying to top each other in their recollections of my dad.

One recalled his suit (“squaresville”). The second,

who’d been naked at the time, had tried on his fedora.

The third asked to see his gun.

The fourth (so she claimed) had said,

“Are you sure you mean gun?”

Now I was having fun, too, getting a look at

my father from a hitherto inconceivable angle.

The waitress came around again. “I’m going off shift in a minute.

Can I get you all anything more before I head out into the night?”

I decided it had better be last call for the Spider Pool girls.

They already had enough tiny paper umbrellas in front

of them to keep the rain off a battalion of leprechauns.

Besides, my pride would be affronted by getting drunken

under the table by a quartet of octogenarian pin-up queens.

The waitress distributed the drinks and kneeled by my side.

“After I leave, I’ll be doing a set at the Cayabonga Club.

I’ll put you on the guest list if you like.” “You’re a singer?”

“Chick vocalist, please.” The Cayabonga Club, an after hours

hole-in-the-wall in Redondo Beach that catered to a mixture

of surfers and gangsters, was a little off my beat.

“I have to make sure these ladies get home safely.

Maybe I’ll see you again sometime.”

“Count on it,” she said, grabbing up her clippers and slipping away.

P.I.-client confidentiality forbade my discussing

the contemporary end of the case with the models,

but since it wouldn’t threaten them now,

I decided to share the story of the drowned girl way back when.

None of them had been friendly with the victim,

but all were intrigued by the same detail:

the moving of the body from Greenacres to the Spider Pool.

It gave them chills, even from a distance of sixty years. The man with the

blanket might have sat in his dark Town Car among the trees at the edge

of the grounds for hours, watching and waiting

for them to finish playing mermaids and satyrs.

I was ready to pull out their chairs and call it a night

when Jade walked in, her left arm loaded with exquisite plumeria

leis which she placed around the necks of the Spider Pool Girls in tribute.

She insisted on taking a series of selfies with them, some glamorous,

some hilarious, then sat and talked about her house and their careers

for a full ninety minutes until the club was about to close.

We walked them to their limos and returned for French Seventy-Fives.

Any nightspot in southern California will

always stay open late for a major movie star.

So we were permitted to sit side by side on the bar

while the working stiffs put the joint to bed.

I told her the story laid out in the case notes,

and shared the Spider Pool girls’ reaction to the tale.

“You know, it never occurred to me to wonder if she might have

drowned someplace else and her body been moved to my house,”

she said. “I naturally assumed it happened where I found her.

But if so many other elements match up, why not that one?

I want you to keep digging. Isn’t that what your father would have done?”

“I wouldn’t know. But something’s bothering me. If your theory is correct,

and you are this version’s version of Jack McDermott, don’t you also

have to be Harold Lloyd, since you’re the movie star in the movie?”

Instead of answering, she put her arms around my neck

and whispered, “It also raises the question:

Who’s the new superintendent, the man

with the blanket who moved the body?”

“Who says anyone moved the body? Are you sure

we aren’t just collaborating on a screenplay?”

“Maybe we are,” she said. “If so, it needs an ending.”

**

I had crashed on the couch in my office for a full year

before drunkenly stumbling one night into the switch that

lowered the Murphy bed out of the wall. Pushing it back

up in the morning was now my daily workout program.

Jade had walked me to my door the night before,

and draped one of the plumeria leis around my neck

before kissing me goodnight on the cheek.

Her breath smelled of apples, and in her eyes,

when she looked at me in close-up,

an irreconcilable cocktail of mischief and injury glimmered.

Who was she, I wondered, when she wasn’t busy being someone else?

**

My brother and I had put our mother’s house on the market.

Soon, I wouldn’t have the right to visit my old tree-fort.

So I climbed out of bed and into my ragtop woody

to make one more pilgrimage to Woodland Hills.

It wasn’t out of my way to stop at the “Made in the Shade”

nursing home in Sherman Oaks where Maggie Amberson

was playing out her string. My timing turned out to be good.

Carrying a box of profiteroles from John Kelly, a confectionary

in Santa Monica, I found her in a reasonably cozy room,

lying abed watching an early Jade Bellinger movie

streaming on Netflix. It had been her first starring role

and offered the pleasure of seeing a good actress

caught in the act of becoming great. She played

a high school teacher accused of having an affair

with one of her students. She could extricate and exonerate herself,

but only by revealing that she was having affairs with both

the boy’s father and mother, unbeknownst to either,

a delicate situation. Somehow, she made this piffle believable,

walking multiple tightropes without ever missing a step.

A nurse nearly Maggie’s age, her name tag identifying her as “Millicent,”

shuffled in balancing a tray of lime jello, a scoop of mashed potatoes

and what appeared to be a cube of meatloaf with carrots and

peas around it segregated into their own little compartments.

She paused on her way out to glance up at the screen and mutter,

“She ain’t no Kate Hepburn, but she’ll do.” I felt bad for her,

stuck in a deadly dull job where nothing new would ever

happen, unless you counted the patients passing away.

She didn’t even have the comfort of a glamorous past to look back on.

I handed the box of profiteroles to Maggie, and she

accepted them as her due. The gifts from adoring men

may have declined from jewelry and furs to

a quick sugar rush, but it perked her right up.

I sat on the bed and watched with her until the closing credits rolled.

“She was such a dear to us last night,” Maggie said. ” I wanted

to see some of her work while the memory of her was still fresh in my mind.”

I hardly knew why I was there. Because she had met my father?

What was I hoping to find traipsing around in his fossilized footsteps?

“I’m glad you came,” she said.

“Me, too. It was wonderful hearing you talk about my dad.

But there’s something else I’d like to go back to, if I may.” She nodded.

“The girl who drowned, in 1957, are you sure you didn’t know her?”

“I’d met her, I’d seen her. Both at the Spider Pool and at other photo shoots.

But I didn’t really know her, except by reputation.” She paused, as though

inching into deeper water. “What was her reputation?” I asked.

“I guess it doesn’t matter now,” she said. “Who could it harm? They said,

and maybe they were just being catty, that she wasn’t exclusive

to Harold Lloyd. That, in fact, she sometimes went with another girl.”

“Do you remember which girl?” “No, honey, I only know it wasn’t me.”

She sighed, rather theatrically. “Maybe I should have tried that side of the street.

I’ve gone through a half-dozen husbands in my life—

they had a habit of trading me in for the newer models—

and I have two children somewhere in this world.

I get a check or a money order from one of my exes every

once in a while, but after the kids were taken away from me,

I lost track of them completely. Last night, my old Spider Pool pals

promised they’d stop by. Or maybe I can get out to see them.

They’re the closest thing to family left to me now.”

Maggie excused herself. It was time for her nap.

When I got to the top of the ladder and opened the hatch,

(really just a crude door, but I had always thought of it as “the hatch”),

I found myself looking into the eyes of a boy about twelve,

a Tom Sawyer knockoff in a backwards baseball cap.

He froze for a moment, as a squirrel might just before lighting out.

He had the cigar box on his lap, open, and had been studying the cards.

“I was just… doing some homework,” he said, finally.

“Yeah, that’s what I used to do here, too, a long time ago. You live nearby?”

“Yeah, right up on Woodlake. I’ve been here plenty of times.”

When I didn’t say anything, I guess he figured he owed me an explanation.

“My parents fight a lot,” he said. “Sometimes I pretend that I’m stowing away on a ship.

I bring a bottle of water and some hard bread.

The branches moving in the wind are like the masts and sails of the ship.”

“Where are you bound for?” I asked. “Around the horn,” he said, grinning.

“And Parts Unknown. I’ve always wanted to go there.

I’ve never seen you here before, though. Do your parents fight a lot, too?”

“No, I don’t have any parents.” “That must be nice.”

“Not really. It’s kind of lonely. You know, I built this

fort when I was just about your age. Those are my cards

you were looking at. He ducked his head and mumbled something that sounded like,

“So I’m like something something, like, awesome, something something, like, something, like totally,

like, something, like, awesome, like, something something, like, whatever.”

I knew just what he meant.

“The house is for sale,” I said. “But until we sell it,

you can come here whenever you want. Maybe I’ll see you again.”

“I think you will,” he said, returning to his homework.

**

I found Jade stalking around with a script in her hand,

gesticulating and running lines, playing all the characters in a scene.

She invited me into the kitchen for a glass of wine.

When she opened the refrigerator door, I saw an

events calendar held to it by a magnet. I would

have liked to take a closer look at it, but when

she closed the door, she was standing in front of it.

“I checked the newspaper accounts of the girl’s death.

They didn’t have much to say about her. More about you.

Exactly where were you when your friend drowned?” I said.

“In Mazatlán, playing a Mexican whore. A very solid alibi.

I was gang-banged by an entire drug cartel.

You could ask them if you don’t believe me.”

“And where was she?”

“House-sitting somewhere, I think. A lot of out of work

actors house-sit. It not only keeps your ass off the street,

but it’s a good acting exercise. You have to act like

you know what you’re doing and can take care of things.”

“If she was house-sitting, how did she end up dead in your back yard?”

“I gave her the code to the gate. I told her she was free to use the pool any time.

I need to go. My agent is taking me to lunch.”

I’d been diligently refilling her glass with chardonnay,

hoping it would send her to the bathroom and

give me a chance to look at the events calendar.

But she’d kept her body between me and the fridge,

almost aggressively, before ushering me to the door.

I needed to find the other end of her tunnel.

This time, saying goodbye, she kissed me on the lips.

It wasn’t a passionate attack, with her nails dug into my back.

Rather, it was soft and sweet and slow, almost thoughtful,

her nails tracing soft lines down my neck, her tongue seeking

gently for something in my mouth, as though trying not to wake me up.

My blood didn’t boil, but it simmered real hard.

Days afterwards, it occurred to me that it was how

Jade Bellinger always kissed in her movies.

“My blood didn’t boil, but it simmered real hard.”

**

It would need to go more or less laterally, and given the prankish

nature of Jack McDermott, its terminus was bound to be somewhere

the eccentric silent movie director could pop out and put a scare

into his cronies. A watering hole was my first guess.

So I bent to the task of examining old business licenses.

He had built the house in the hills in 1923.

So the gin-mill, or roadhouse, would need

to have been extant shortly thereafter.

When I realized there was only one barely usable road back then,

it became easier still. There were a great many other streets and

developments now, but the original road, the one the donkeys

had hauled the movie sets on, was still there, though in far better condition.

But I couldn’t find any business licenses before 1940.

So I did what my dad would have done and hit the streets.

I drove around, and asked around, and then did it all over again.

After three days of wearing out shoe leather, I chanced upon a curio shop

down on the flats called “Madeleines” and there found what I was

looking for: a wheel of poker chips that came with a partial set of

shot glasses from a card room and dive bar called “Jack’s or Better.”

I figured McDermott for a partner in the place.

Each glass bore the year 1926, and on each there was a street address.

**

I had hoped to find some kind of old-timey mercantile operation on the spot.

A general store with gingham dresses, barrels of nails and all the latest catalogues,

from Montgomery Ward to the Farmer’s Almanac.

Maybe the case had made me a little goofy.

But when I found the address where I’d determined the tunnel must end

and eased into the little pull-out, barely large enough for a compact car,

there was no business and no residence.

I was parked in front of a open field.

The donkey traffic may have been heavier in 1923,

but there was still one complete ass on the road.

I climbed out cursing myself, my father and my luck.

My lot in life had turned out to be vacant.

I stomped around the field looking for I knew not what.

A hollow tree? A ski lift? Climbing wearily back in,

I dropped my phone on the ground. Trying to pick it up,

I accidentally kicked it under the car.

Getting down onto hands and knees to retrieve it,

I couldn’t help noticing that I had parked directly over a manhole.

Not a real manhole. It was made of wood, with some astroturf

and artificial leaves and twigs permanently attached,

like a sniper’s helmet with branches stuck to it.

Pretty clever, really, when you thought about it.

If you drove here looking for the entrance to

Jade’s tunnel, you were obliged to park over it,

removing it from sight. I motored about a half-mile uphill

to a more spacious turnout, left the woody and walked back down.

**

As I’d anticipated, the grade wasn’t steep

and there were handrails all the way,

good ventilation, even a few benches for taking a rest.

If the homeless community ever tumbled to this tunnel,

an underground city would grow up here overnight.

I knew she was scheduled to be on set all day.

I only needed a few minutes, but breaking and entering makes me nervous,

so I didn’t even pause to peruse the labels in the wine cellar

but headed straight for the kitchen. Relieved not to run into

workmen or a cleaning woman, I looked intently at the events calendar.

I didn’t know why it was so important to me.

But I felt like people who needed my help

were yelling at me from behind thick glass.

And why was an image of Jades’s mouth messing with my head?

Probably because of the lipstick encircling a date on the calendar,

a deep red heart around it with a

notation saying “Back from Mazatlán.”

I wondered why she would need to circle the date of her

own return, and almost voluptuously, in lipstick, at that.

**

I kept poking around, but there was really no reason

to believe the girl’s body had been moved to Jade’s pool.

Why, I wondered, did Jade herself

keep insisting on these parallels to 1957?

Could my client have revealed part of the truth to me, and concealed the rest? For instance: she told me the girl had

been house-sitting, but hadn’t mentioned where. But if she had

been house-sitting for Jade, there had never been any need

to move her body. When I got through to an assistant

producer on the picture Jade had been filming in Mexico,

he told me production had been shut down for a week

due to the director suffering from “flu-like symptoms.”

It hardly mattered since Ms. Bellinger’s only

remaining scene had been cut from the script.

I checked flight manifests, talked with ticket agents,

security personnel, pilots, air traffic controllers

and then with cabbies, a lot of cabbies, until I was able

to sketch a picture of Jade’s return home that rang true.

Something Maggie Amberson had said about the first drowned girl,

that she’d been rumored to enjoy the company of other girls,

combined in my mind with that mark on the calendar.

Might it have been not a heart drawn in lipstick

but an actual kiss, planted there by a lovestruck

girl, awaiting the coming of her own true love?

**

I needed footage from security cameras,

but my client was creeped out

by having them on the premises.

Perhaps it was too much like being at work.

But now I had no way see if anyone

had driven in or out on the night of

Jade’s return before she herself was dropped off. Let’s see:

If she’d entrusted her friend with the key-code for her front gate,

what else might she have shared? When I’d gone back to look

at the calendar, I’d taken a quick peek into the fridge

where a half-empty bottle of champagne sat beside

an untasted chocolate soufflé, two big ahi fillets

and several small produce department bags of vegetables.

The champagne was top shelf, the soufflé looked

homemade, the ahi and veggies were marked “Erewhon.”

**

“I’ve solved the case.”

In the name of showmanship, I had come through

the tunnel and into the house from the wine cellar,

though without any wine. Jade barely lost her composure,

greeting me as though I’d been expected. “I was wondering

how long it would take you to find the other end,”

she said. “Have you made any progress?”

She sounded genuinely hopeful.

“Yes. I even know who moved the body.

We should have champagne to celebrate.”

I went to the fridge, lifted the metal cap off the half-filled

bottle of Taittinger, made a point of noticing that

that no pressure was released, and said,

“What do you know? It’s flat. Those things usually work so well.”

“Well, tell me. That’s what I’m paying you for, isn’t it?

It wasn’t a superintendent of police, was it?

That would be too much to ask for.”

“No,” I said, taking a hit off the bottle. Only

private eyes can enjoy flat champagne. “It was you.”

“Me?” Her eyes opened, but only by a fraction, with mild

indignation mingled with anticipation. “Why would I

move her, and where would I move her from?

Are you saying I killed her?” “Oh, no. That wouldn’t

line up with 1957. In fact, symmetry with the events

at the Spider Pool may be the only reason you took

the trouble to move her at all, since you only

moved her from the jacuzzi to the pool.”

She smiled, indulgently. “Our screenplay

appears to have gone off the rails,” she said.

“There’s no record of you ever taking a commercial flight from Mazatlán.

That’s because you chartered a plane, and returned a day

early to surprise someone. Your cast mates and crew in Mexico

thought you were still there, in your bungalow with a Do Not Disturb

sign on the door. Ordinarily, you would have had your

on-call car service pick you up at LAX. But when you called

them, you found out they’d already dispatched a car

to pick you up, not at the airport but at your house,

formerly known as the “Spider Pool.” You ended up cabbing

home, but when you got there, the place was empty.

Your house-sitter was nowhere to be found.

“This is fun,” she said. “It’s like a kid being told

a story all about herself. What happened next?”

“Your surprise had gone flatter than this not-so fizzy wine.

So you slipped out of your clothes, and took the bottle of champagne

you’d brought home in the cab out to the jacuzzi to wait for her.”

“To wait for who? Who was I trying to surprise?”

“Your house-sitter, your friend, your lovely new young lover.

I knew the date circled on that event calendar—

pointing to the refrigerator—”had a hidden meaning,

but it wasn’t hidden very deeply. Someone was anxiously

awaiting your homecoming, someone who loved

you and wanted to welcome you with a fancy dinner.

But it wasn’t the dinner of a grateful house-sitter.

The old-vine zin, the organic vegetables from Erewhon,

the ahi fillets, the homemade desert, everything about it was romantic.

But it wasn’t until I spent a lot of your money

greasing the palms of a pilot and a cabbie

that I knew the meanings were actually two in number.

The date was a day later than you actually returned.

When you came home a day early to surprise your darling,

it ended up accidentally spoiling both of your surprises.

The midnight supper supplies I saw in the fridge weren’t there when you arrived.

They weren’t there yet because your friend had summoned the

car service—whose driver mistook her for you—

and gone way down to Erewhon on Beverly Drive

in the Fairfax district to do the dinner shopping.

That’s why you’d been obliged to take a taxicab.”

“OK. Then what did I do?” Again, she sounded

like a little girl reliving her origin story.

The color of her eyes could shift, within minutes and

without the help of contacts, from her namesake stone

to aquamarine, and thence to the hazel of an enchanted wood,

and her portable patch of shade—as if an invisible handmaiden

held an equally invisible parasol over her at all times—

became dappled for a moment, illumined by

shafts of sunlight that lay along her hair.

It happened at that moment.

“You took off your clothes and carried the bottle of champagne

out to the jacuzzi. You had intended to open it in front of her,

but since you had to wait, you popped into the whirlpool and

started to hit on it by yourself. You’d had a number of drinks

already on the plane, and a few more in the cab. So you were

rather plastered when you slid into the warm water with

the cold champagne. Half a bottle later, you passed out.

When the car service returned from the store, you were quite dead.”

**

She laughed. Like her surprise and her sense of anticipation,

her laughter seemed quite real. It was real. Everything she did in character

was as true as me or you. And she was always in character.

“Wait. I thought I moved her from the jacuzzi to the pool.”

“And so you did. For a long time, you’d been seeing yourself as Jade Bellinger,

in the way that lovers have of identifying with one another.

Now you began to see yourself as the writer-director

of a movie that wouldn’t need a distributor

because it was made to be seen by only one man, myself.

You had to wait for a day. A day during which she would stay

face down in the pool and you could prepare for the part

you would play for the rest of your life.

What do you say we make a couple of real drinks, and go

sit in the jacuzzi where the whole mess started and have a

sort of script conference? You can tell me why you hired me

and maybe we can decide how to put our screenplay to bed.”

“Do you like my suit?” It was a fifties one-piece, not

at all daring but maddeningly attractive nonetheless.

“It belonged to Mildred Davis. I bought it on eBay.”

“In that case, I’ll be your Harold Lloyd and stay silent

while you pick up the story and tell me how it all went down.”

“She was my dearest friend,” she said, “who became my greatest love.

When I couldn’t locate a pulse, I tried to breathe life back

into her, but our last kiss was entirely one-sided.

I think she was gone before I got back.

While I sat there, weeping and nearly paralyzed with shock and grief,

I found myself remembering everything she had

told me about the history of her house, about the Spider Pool.

The story of the movie star, the drowned girl, and the detective.

What part could be harder to play, I thought,

than an actress greater than oneself? At first I was terrified.

I expected I’d be caught out within minutes.

But no one called me on it. When the police responded

to my distress call, they assumed I was her.

I answered her door, after all. I was wearing her clothes,

which fit me perfectly, since we’d always been the same size.

My clothes and purse, with I.D. in it, were slung over a

pool chair to give the impression that she’d

decided to take a swim and stripped off.

She had been in the pool long enough when the

law arrived that her face was a bit bloated.

And I spent the twenty-four hours before calling a response team

making sure my hair and make-up duplicated her own style.

“If they’d thought Jade Bellinger had drowned,

the police and the press would have been all over it for weeks.

Declarations of war, famine, pandemic and plague

would be pushed off the front page.

A celebrity coroner would be put in charge of the autopsy.

But if a nobody, some wanna-be from Podunk

(and I really am from Podunk, by the way)

got liquored up and gargled too much chlorine, who would care?

The answer, sadly, is nobody. I knew from our long talks

that she had cut her ties with her family years ago. And I

have no family. So, as her closest friend, I was, ironically enough,

asked to identify the body. I also knew she wanted to be cremated,

so I was obeying her wishes when I had her earthly remains

quickly translated into ashes, which also meant no one

could disinter the body to be autopsied afterwards.

Then, day after day, I waited for someone to challenge me.

No one ever did. It was Jade herself who gave me the idea.

She snuck me in one time through the tunnel,

so she could dress me and send me back out

through the front door, wearing a headscarf

the tabloid photographers had seen her in before.

I took a long walk down the road to the convenience

store on the flats. They all followed me, slavishly.

It gave Jade a chance to slip out undetected to meet her sweetie.

I wasn’t ever sure of what laws I might be breaking.

Fraud? Identity theft? Does it still count if the identity

belongs to someone who’s dead? Elvis impersonators

make a perfectly good living, after all, pretending to be

someone who looms large in the public consciousness.

I broke up with her boyfriend over the phone

(something she’d been considering doing anyway).

I had to assume he would know something was wrong

when I behaved differently in bed. I had no idea what,

well, you know, what kind of things they did together.

I considered telling him that I was trying out new ways

of kissing and talking and fucking and stuff

as a kind of method actor’s means of preparing to

play a new role, Catherine the Great maybe.

Instead, I just phoned him and broke it off.

He took it surprisingly well.

The love interests of high profile actors are always ready

for the chop. Too much temptation, especially on location.”

“But you . . . she . . . are . . . were . . . one of the most recognizable people on earth.”

“Did you recognize me?” No, I had recognized who I thought she was.

What is it that they say in the old movies? The mind can play strange tricks.

“I had no future as myself. My only speaking role had been left on the

same cutting room floor where I’d gone all the way with the director

in order to get the part in the first place. I couldn’t bring her back,

but maybe, in a way, I could. I could give up my life to keep her alive.”

“And to become a fabulously wealthy, world renowned

movie star,” I said. “Let’s not forget about that.”

“I don’t expect you to understand,” she said.

“We were the sisters neither of us had ever had.

We were very close, closer than close, if you know what I mean.”

“I believe I do.”

“You know that movie where she plays the falsely accused teacher?”

“Yes. In fact, I saw a few scenes from it the other day in a nursing home.”

“Well, that’s how it started. She wanted to do research for playing

a bisexual. She had never been with a woman. Neither of us had.

At first, it was merely exciting. Since we might almost have been twins,

it was sort of like masturbating in front of a mirror. And it was

convenient for her. She didn’t need to go on the prowl, as it were.

Her steady beau was off making a movie in Singapore,

giving her plenty of time to concentrate her ‘research’ on myself.

We already slept together sometimes,” she said,

“in a sisterly way. So it was only a matter of scooting

a few inches closer to begin our . . . studies.”

She blushed, and I wondered if you could fake a blush.

“So you were the movie star’s girlfriend, which makes you

the girlfriend, and are now the movie star herself.

As her, you are-were the director Jack McDermott, and you were,

as you, the superintendent because you moved the body. You only

failed to be the movie star’s wife.”

“But I do have her old swimsuit, so I can still

get an Oscar for best wardrobe,” she said.

I’d been asking myself the wrong question.

The question wasn’t who she was. The question was who she wasn’t.

**

“So why hire me? It makes no sense.”

“I’ve been playing her for about two months now,”

she said, “but only in real life.

I haven’t yet given a performance as Jade Bellinger.

You were my warm-up. If I could fool you, I mean royally,

I felt I’d be ready for the big screen. But I always intended to tell you.

I needed to know that you knew. Yours is the only review I’ll ever get.”

Now, I’m as naive as the next guy, especially when it comes to

beautiful women, but I’d never thought of myself as a gull or an easy mark.

“You’ll forgive me if I’m finding all this a little hard to believe.”

“Will you excuse me?” she said. “I need to use

the powder room, as they call it in the old movies,”

Just as my patience was wearing thin and I’d wandered

into the living room in search of my client, the purple-haired

cocktail waitress/chick vocalist who had served our

table at the reunion walked in from the back of the house.

“What a pleasant surprise,” I said, pleasantly surprised.

“You told me I could count on seeing you again,

but I never would have guessed it would be here.

Are you a friend of… of Jade’s?”

“Yeah. I thought she was here. Listen, I need to

use the facilities. You wanna do some coke?”

“No, I’m kind of in the middle of something.

You go ahead.” A minute later, the nurse named Millicent

walked in the front door. In the same careworn

dustbowl monotone I’d first heard at Made in the Shade,

she said, “Miss Bellinger sent a car for Maggie Amberson.

She’s out there now at the curb, taking a little nap. And I gotta pee.

You know where the lavatory is in this pile of bricks?”

I waved a hand and pointed west. “Over that way, I think.

Just hang a right at the solarium.” It was going to get

awfully crowded in the powder room, I thought, wishing

for greater privacy. Finally, I heard Jade coming back.

But it turned out to be the twelve-year-old boy from my tree-fort.

“I brought you some water and hard bread,” he said,

holding out a canteen and a stale baguette. Apparently,

this was the scene where I pulled all the suspects together

and told them who was who and what was what,

except that I hadn’t called anyone.

I eyed him warily while taking a big swig on the

canteen and almost choking to death on straight vodka.

“It’s the water my dad drinks when my parents are fighting,” he said,

slowly transforming himself into one of the most famous women on earth.

The backwards baseball cap was skimmed toward a hat rack

in the corner and her long auburn hair tossed around as it tumbled down.

The dirty gray hoodie was pulled off and the equally filthy camouflage

cargo pants followed to reveal a white, rhinestone-encrusted bustier

and bell-bottomed silver velvet trousers. Under the clunky

sneakers were delicately beaded Italian silver sandals.

“I feel like my head just sailed around the horn,” I said.

“And, hey, how about those parts unknown?” she said, giving a little tug to the bustier.

Was there anyone she wasn’t?

For a moment I feared that she was going

to walk into the powder room and I was going to walk back out.

“The one thing,” said Jade/Waitress/Millicent/Backwards Baseball

Cap Boy/God knows who, “that she didn’t know and I found out

is that the son of the Spider Pool detective is a private dick

working more or less the same beat as his dad.

He lives above a tiki bar out in Venice Beach.”

Now I knew how my father had felt.

I had found the truth, but could do nothing with it.

“Jade was one of the greats, but she wasn’t half the actor that you are,

you tomboy bombshell. I have just one question

for you. Well, two, really. But only one for now.”

“Yes?” She cocked one hip, put her hand on it and threw back her hair.

“How did you manage the business with the butterflies?”

“Well,” she said, teasing and taunting, flirting and flaunting.

“You start with caterpillars on your nipples.”

Since I had seen all of Jade Bellinger’s movies,

I had glimpsed this almost unendurably desirable

girl in the altogether, feigning the final proofs of love.

Standing before me, her body was stillness italicized and she

smelled like desert wildflowers that had bloomed upon the sea.

She was, as ever, attended by her personal patch of shade,

but now it was accompanied by a

little pocket of the Santa Ana Wind,

alluringly warm and more than a little disturbing.

“I’ve never slept in a Murphy bed,” she said.

“But I suppose it would be kind of off the wall.”

Deanna, Karina, Maggie and Deborah Eileen were

the first four residents of “Model Home,”

a retirement mansion more like a sorority house with turrets,

a butler, an indoor pool, 24-hour massage service, fireplaces

(kind of foolish in L.A., but the Spider Pool girls would crank

the air conditioner until they were cold enough to require a fire),

a good library, an enormous kitchen (and a roundelay of guest chefs),

a sewing room, a rumpus room where they read aloud together,

a projection room, a greenhouse, four-poster beds,

every amenity a burlycue queen could ask for,

set on a bluff overlooking the ocean in Pacific Palisades

so the girls could walk to the beach for their daily exercise.

They had even included a helicopter pad so Jade could fall by

out of the sky. Movie stars shouldn’t have to deal with traffic.

Occasionally, I would drop in myself for what we called

“cordials,” meaning shakers of icy vodka martinis.

Well, a girl needs to wash down her meds with something, after all.

Though well received, I wasn’t the most welcome of their visitors.

Maggie’s children had finally returned to her life,

with their children, their children’s children,

their children’s children’s children and their kids in tow.

They’d spent years finding each other—different fathers,

different cities, divorces, foster homes, feuds, fallings out—

then even longer tracking down their mother.

They’d known her by different names, neither one her own.

On the verge of giving up, they’d hired a low-rent gumshoe

who lived above a tiki bar on the outskirts of Venice Beach.

That may have accounted for all the free drinks.

The place had been bankrolled, all expenses paid in

perpetuity, by my former client, in answer to my second question:

Would she, in exchange for my silence—

almost as funny as that of Harold Lloyd himself—

in the matter of the echo of an accidental death which

had occurred in 1957, underwrite this hostel for old

glamor girls? The pool boasted a wicked-looking

tile tarantula on its bottom, itself an echo of

the site of the first unfortunate girl’s passing,

which once was known as the “Spider Pool.”

These days, it’s the address of Jade Bellinger,

an extraordinarily gifted actress whom I have never met.

Such is the life of a private eye

Next week: Part 4

Michael Larrain was born in Hollywood, California, in 1947. He is the author of nineteen books of poems, children’s stories and prose fiction. His novels Movies on the Sails, As the Case May Be and Fair Winds & a Happy Landfall are available in both paperback and Kindle editions on Amazon. He makes his home in Sonoma County, California.