No, you’re not seeing double. This is Part 5 of the poet’s extraordinary narrative poem about his fictional private eye. Each is told by our one and only gumshoe, each a separate adventure in the streets of Los Angeles, and in each a dame. Of course. If he can figure her out, he can solve the crime. Let’s see how he does in this episode. One more to go next week.

The Life of A Private Eye

A Noirvelette in Verse

By

Michael Larrain

Part 5: Quadruple Indemnity

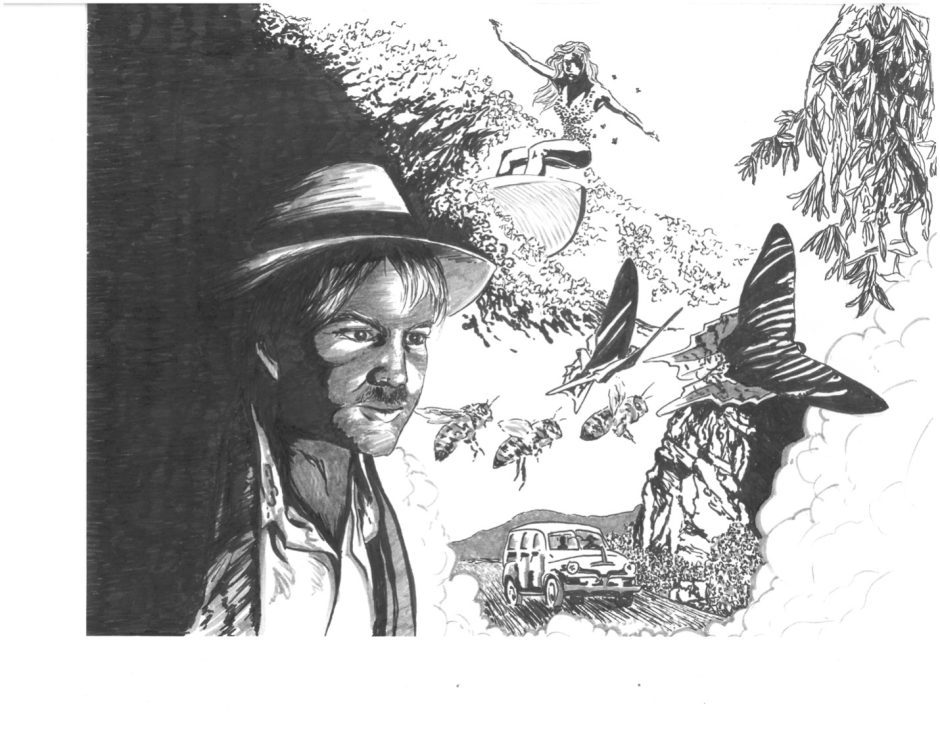

Original illustrations by Katherine Willmore

My doctors had been advising me to get more exercise,

so I learned how to put myself into a trance and slipped a

couple of useful ideas into my post-hypnotic suggestion-box.

The first was to take nightly sleepwalking perambulations.

The second tricked me into believing that while

conked out and about, I mistake water for vodka.

As result, I awaken both well-rested and rehydrated!

Of course, I’m unable to map out my route, but what matter?

I may not know where my nocturnal footsteps have led,

but judging by the newfound muscularity of my calves,

I’ve traveled a considerable distance and come to no harm.

These late night excursions had been going on

for quite a while when, one morning about a month ago,

a beautiful blonde woman sauntered through my office door.

No other verb would do. Only rare beauties can really saunter.

They are the sauciers of walking, with that exquisite,

almost floating equilibrium of hauteur and languor.

The rest of us just put one foot in front of the other.

I assumed she was a prospective client

until she referred to the tavern where we’d met the previous night

shortly before last call at two a.m. I had turned in at ten.

A few weeks before, after I awoke one night naked

on the sidewalk in front of the tiki bar I live above,

I had begun to wear silk pajamas to bed.

It’s a neighborhood where most anything goes,

but even in Venice Beach there are cops who might

object to a gent walking out in naught but his fedora.

I knew the dive she mentioned well enough

to know that in my jammies I might just have

been the best-dressed man in the joint.

She was in her mid-forties, about five-nine,

alluringly slender in a slinky red dress that clung to her

like a happy combination of salvation and molestation,

hair the color of Honey-Nut Cheerios,

legs as long as a tale of woe. And, bless me, freckles.

An abundance of freckles dusted across her face

and shoulders, her arms and the tops of her breasts.

I was doomed. Freckles in a woman’s cleavage

have always been my favorite flavor of French toast.

My first long look raised a question too undiplomatic to ask:

Had we slept together while I was asleep?

“I’m afraid my memory is a little cattywampus,” I said.

“I’d had rather a lot to drink.”

How was she to know I’d only knocked back water?

“Could you remind me of your name?”

“There’s no need to be embarrassed. We didn’t

get around to exchanging names. I’m Jenny. With a ‘y'”

And a why not? I thought, but wisely stayed quiet.

She rummaged around in a big straw beach bag

and came out with a business card. It read

“Jenny Rostand, Snap-Shooter”

The background was a black & white photo of a grizzled

old wino standing in the surf with his trousers rolled up,

his right hand resting on the neck of a goat.

“You’re a photographer?”

“I was. An art photographer, if you will. I showed in a few

galleries around town. I hadn’t really made a name for myself,

though, and when a lot of new money began moving in

and most of the painters and photographers I knew were driven out,

I was driven into the arms of a . . . speculator. In other words,

I married money. It wasn’t my sole motivation,

but I confess to having been nervous about being a single

woman art photographer in her forties with no prospects.

Now I guess I’m what my closest friend

called me the other day, a ‘cosseted chatelaine.’

My husband and I had fought that night.

It grew ugly, and I had to get out of the house.

“I was charmed when you looked right into my eyes

and said we should give dust motes the vote,

but only when they are swimming in shafts of sunlight.

We had one dance, just before the band packed it in,

then you wandered out the door.

“The bartender told me you were a local P.I. and where to find you.

“If you can deduce as well as you dance,”

she said, “You’re the sleuth for me.”

We had danced? Well, if you can walk in your sleep,

who’s to say you can’t dance? Dancing, after all, is only flirtatious walking.

I hadn’t been able to get around on a dance floor in years.

Apparently, my sleepwalking mind was unaware of my back trouble

and wrote better dialogue than I came up with when awake.

What had I been doing in a tavern? It’s tricky leading a double life

when one half is on the other side of a curtain rubbing against your dreams.

I introduced myself and invited her to sit.

“Or you can lie in the hammock, if you like.”

“A woman in a very short dress is especially careful.”

A home/office above a tiki bar demands a hammock,

along with my private emergency exit, a two-story stripper pole

next to the palm tree outside my window. As an original investor,

I had leveraged management into providing me with it,

along with a tab that never came due at the bar downstairs.

Women approach hammocks and their postures in them

differently than men. A guy just straddles the thing,

lies back and knits his fingers behind his head.

A woman studies the hammock and works out her strategy

for settling into it, usually side-saddle.

A woman in a very short dress is especially careful.

Jenny lowered and arrayed herself in a leisurely manner,

crossing her legs in slow-motion—I swear I could have

watched a tropical moonrise as she swung one over the other—

to signal her readiness to get down to business.

“I charge three hundred dollars a day,” I said, “Plus expenses.

What can I help you with?” I sat down behind my desk,

a handsome old hardwood door shipped from a crumbling chateau in Paris

and propped up by two mini-fridges I keep handy so that perishables such

as pimento olives, maraschino cherries, limes, mango puree, dry vermouth,

dark rum and Grey Goose don’t spoil in the southern California heat.

“I think I may be cheating on my husband,” she said.

Think? I thought. May? How good could it have been if she wasn’t sure?

I didn’t trust myself to speak, so I shot her an inquiring glance.

“You’re right,” she said, “I should explain.”

She wriggled around in the hammock,

getting comfortable and making me squirm a little myself.

“Lately, I’ve been waking up in the middle of the night

at critical points in a recurring series of very disturbing dreams.

The dreams are highly erotic, and charged with a sense

of both anticipation and foreboding. Just at the point

when the…. action is about to be consummated, I awaken.”

She paused, uncertain of how to continue. Fortunately,

I found my voice. “Well, I said, “Everyone has such dreams.

You can’t be held responsible for the workings of your subconscious.

And it’s hardly something I could investigate in any case.”

She had ended up lying on one hip, facing me, her dress hitched up

far enough to display a rusty splash of freckles across a pale thigh.

“There’s more,” she said. “When I awaken, my husband is

sleeping soundly at my side, and I try to snuggle back down,

but I become aware of certain . . . evidence of actual adultery having occurred.”

She looked down, shaking her head in bewilderment.

“We’ve haven’t even celebrated our first anniversary,” she said.

“I haven’t had time to be unfaithful.

I’m a very light sleeper, so I know that I

would wake up if he had taken to . . .

tampering with me while I was unconscious.

I don’t know what’s going on. But I’m scared.”

“I assume this ‘evidence’ is physical,” I said,

“but we can keep it on a need-to-know basis.

I don’t need to know unless you think it’s relevant.”

“Let’s just say I’m considering buying a bidet,” she said.

Before a long pause could grow into a yawning silence,

I offered her a drink. She assented and I built her a big mai tai,

my usual cocktail for anyone kicking back in the hammock.

“I still don’t know what you’d like me to do,” I said,

after she’d taken a few sips and smiled.

“Perhaps you need a therapist rather than a private investigator.”

“This is going to sound crazier than anything you could

tell to a therapist,” she said, “but I believe I’ve been sleepwalking.”

“And committing adultery in your sleep?” “That’s right.”

“And you’re certain your husband hasn’t been trifling with you?”

“Absolutely. It’s happened on a few nights when he was out of town.”

“Do you want me to follow him?”

“No,” she said, “I want you to follow me.”

**

I certainly needed the money.

You can only live for so long on

pimento olives and maraschino cherries.

But wasn’t I ethically obligated to mention

that I too had been going out on sleepwalking forays?

For all I knew, I could have been her illicit lover,

neither of us with the slightest recollection of our trysts.

Would that count as dating? Would it even count

as sex if you didn’t know you’d had it or with whom?

But if I was careful to stay awake while staking her out,

why couldn’t I follow her at a discrete distance

to see if she was indulging in unconscious indiscretion?

If she left her home and met someone, I could intercede,

take him aside and fill him in on her situation.

He might not even know he was taking advantage.

Of course, she might have had encounters with any number of men,

none of them too fussy about how or where they satisfied their lust.

I decided to dummy up about my exercise program for the time being.

She needed help. Maybe my own expeditions under the moon,

exempt from care and the concerns of this world,

would give me an edge in helping her.

Anyway, I accepted her more than generous retainer.

**

A few years ago, a concerted effort to gentrify Venice

drove out many of the longtime residents: artists of every sort

suddenly found the Black Rock desert of Nevada more congenial.

Or they drifted up to Oregon. Or down to Costa Rica.

But at my end of the boardwalk, not far from the Santa Monica Pier,

street performers and buzz cut skate-queens with cockatoos on their shoulders

still ruled the scene, tattooed lady wrestlers, body builders at Muscle Beach,

leather-vested bikers, shirtless bleached blond surfer boys, pushers and puppeteers.

Even the zoot-suited three-card monte dealers who had emigrated

from the sidewalks of New York sported multiple ear and body piercings.

It was hard to believe that only a few miles away along the canals,

some of the wealthiest people in Los Angeles lived in houses so

expensive I could get arrested for parking in their neighborhood.

Though that’s exactly what I found myself doing the next night.

My old woody—a 1941 Ford Super Deluxe

with a 221 flathead V8, a three-speed manual transmission,

bird’s-eye maple and mahogany paneling, and covered

with classic shredder stickers—was rather out of place

so close to her husband’s new black Range Rover,

on the side of their two-story corner lot home on Grand Canal,

next door to the vacation manse of a Saudi prince.

I’d been crouching on a charming little bridge that led over the canal

for about an hour, sipping from a thermos of doctored coffee to stay awake.

I couldn’t stop thinking about those freckles on her thigh.

Was it wrong of me to be dreaming up names for them?

Even my limited math skills had been equal

to noticing they were three in number.

Maybe I should demand a recount at close range.

It would have been easy when she sauntered out her

door in an aquamarine chiffon baby-doll nightgown.

How could she saunter in her sleep?

How could anyone maintain such unearthly equipoise

when their awareness of their own body was missing in action?

I had been ready for her to walk off in one direction or the other

but she ambled with her usual nonchalance to the canal’s edge.

Was she going to do a swan dive in her nightie?

No, she went directly to a small private dock

where a one-woman kayak was tied up.

I’d been prepared to follow her,

as slowly as necessary,

as long as she was on foot,

but now it appeared I might need a zodiac or submersible.

I hurried back up to the woody, pulled out the Rick Noë longboard

a cash-strapped client from Santa Cruz had given me in lieu of payment

and ran—well, hobbled real fast, in flip-flops—back down to the dock,

slipped into the water and paddled out on the

strangest tail job of my long peculiar career.

Letting her get a head start, I sat up,

pulled out the Swiss Army knife I always carry when on a case,

cut off the legs of my Levi’s and consigned them to the deep.

My biggest problem now was staying awake.

If sleep overtook me, I too would be somnambulizing.

Wishing to keep my wits about me, I had tried and failed

to cancel my post-hypnotic suggestions. I’d be sleep-stalking her.

When I was close enough to see her craft moving through the calm water,

I tried to synch my own strokes to those of her double-bladed paddle,

hoping to maintain a consistent distance between us.

I wanted to stay close enough that I could keep her in sight but hang far

enough back that I wouldn’t spook any waterborne would-be paramours.

Did she even know where she was going?

Or was some nefarious aquatic Svengali drawing her to him?

I remembered the old “Use Hypnotism to Have Your Way with Women!”

ads in the comic books of my youth. An intense young man

with zig-zaggy lines emanating from his fingertips

now owned tremendous power over tranced-out beauties

who were helpless to do other than his bidding.

You sent away for it and afterwards

you wouldn’t have to worry about how to talk to girls.

Was this a nightly ritual, I wondered, or a one-time-only deal?

Did she set out for a different destination each time?

She hadn’t told me because she had no idea.

It was my job to find out and tell her what she’d been up to.

I didn’t need to know celestial navigation,

to determine our position with near precision.

We were heading west on the Grand Canal.

If we went much farther, we would end up

against the sea gate just southeast of Washington Avenue.

It’s one of two, the other being at the Marina Del Rey breakwater.

The gates provide the means of refreshing the canals of Venice,

opening at low tide to let most of the water drain out,

and closing at high tide, trapping the water for about three days.

We were close enough to the Pacific that I could hear

some late-night revelers on the beach, partying

to the slack-key strains of Peter Rowan’s “My Aloha.”

Then I heard a sound somewhere between a crack and a crunch.

If she was sleep-paddling, it didn’t really matter if I intercepted her,

so I stroked harder, thankful for a night of bountiful moonlight.

When I got next to her, I could see that the nose

of her kayak was wedged up against the grill, or grid

of the sluice gate at the end of the canal. The actual sea gate

which admitted the saltwater and allowed it to depart,

was on the marina side and operated automatically.

I reached down into the water to see if I could free the thing

and swing it around to point it back at where we’d begun.

Before my hand could grasp the kayak, however, it landed on

a large solid object, giving me a start. There shouldn’t have

been anything there. The remains of a harbor seal? Surely not.

It might have drifted down the lagoon, but would then

have been trapped on the other side of the gate.

I forced my hand to explore up and down in the dark water

until it found rough fabric. When I pushed against the fabric,

it gave a little, but only a little because beneath it was flesh and blood.

A drowned swimmer? There was little or no tidal ebb and flow within the canals,

Why wouldn’t a body just sink?

My hand kept moving and found a necktie.

Why would anyone wear a necktie to go for a swim?

No self-respecting surfer would dream

of wearing a tie unless they were in court.

This departed soul was fully dressed.

Not surprisingly, above the necktie was a neck, above that a face,

that of a male human being, judging by the stubble.

I slid off my board and dove down a few feet to see if I could

find a way to pull him loose and haul him to shore.

It wasn’t until I’d worked my way from his arm to his wrist

that I realized he was manacled to the metal grill.

At low tide, his face would have been visible.

Just now he was entirely submerged and all I

could tell about him was that he needed a shave.

Sitting up straight in the kayak beside me,

Jenny might have been staring into the next dimension

for all the attention she paid to me and my discovery.

I wouldn’t have been able to pick a lock underwater

and I hadn’t come equipped with bolt-cutters,

so getting the body to land would have to wait.

I used the leash of my board to lash it to the kayak

and slowly towed her back to her dock.

She disembarked and walked straight to her front door.

Did she know to go in? I wasn’t about to ring the bell.

Suddenly, she woke up, looking around at the water and the sky.

“I know who you are, “she said, “and I know where we are

but I have no idea what’s going on,” she said,

“What happened? Did I sleepwalk?”

I gestured at her outfit. “You did.” “

She smiled coyly. And did I . . . ?”

“No. I’m happy to report than no incidents of canal-going adultery

were committed during the making of this picture.”

I decided it was best not to mention finding a body.

She hadn’t really been there in the usual sense of the term,

and it might save her a world of aggravation later.

She draped her arms around my neck, gave me a chaste kiss on the cheek and said,

“I’d invite you in for a drink, but . . ..”

She pointed upstairs, grinned and shrugged her lovely, nearly

bare shoulders, remarkably composed for a woman who had just awakened

under late summer stars in a blue-green baby-doll nightgown.

“It’s just as well,” I said.

“I have some things to do before I can lay down my weary tune.”

I’ll be here tomorrow night. Sleep tight.”

“Sweet dreams to you, too,” she said, and slipped through her front door.

After I left her, I gave a homeless gentleman a five-spot to use his cell phone.

The desk sergeant listened politely, asked all the right questions

and told me I’d need to come in and sign a sworn statement.

When I got to the station, it turned out that I knew both of the

detectives assigned to the case. Our paths had crossed occasionally

over the years. I’d even been able to help them out a time or two.

So, though relations weren’t exactly chummy,

neither were they adversarial. Semi-collegial, you might say.

They’d already brought the body in and examined it.

“What the fuck were you doing floatin’ around the

canal on a surfboard in the middle of the night?”

I had kept it simple by leaving my client out of it.

“Couldn’t sleep.”

They must have known me because they bought this.

“You calling it murder?”

“Fuckin’ a. Could be some kind of interrogation that ended in murder.

You cuff him to the gate and question him while the tide is rising.

The water does half your work for you.

You keep asking questions and showing him the key to the cuffs.

But whether or not you get what you want, you never use it.”

“You i.d. him yet?” “Yeah, he hadn’t been in the water that long.

“He was a local, one of those yuppie financiers.

“Name’s Green, Andrew Green. A guy who sits at

“a computer all the doo-dah day moving money around.”

“He must have moved some in the wrong direction.”

“Hard to say. We’ll know more in a day or two.

Right now we need to go notify the widow. Care to ride along?”

“Sure.” I couldn’t get back to work until the Rostand woman’s bedtime.

And a man in my income bracket can’t be

acquainted with too many wealthy widows.

Even though I was riding in the squad car of two plain-clothes

detectives as a guest, I wasn’t entirely comfortable.

Imagine how much less comfortable I grew as we motored out to

Grand Canal and the driver pulled in behind 2218, my client’s house.

On the way up the walk, I fingered the still soggy business card

in the pocket of my cut-offs. There hadn’t been time to go back

to the office and change. It’s possible that my outfit

was a bit too casual for a condolence call.

At least my Rolling Stones t-shirt was clean.

“Good morning, gentlemen, if it is still morning.

What can I do for you?” If she recognized me, she didn’t let on.

The lead investigator—his name was Hannigan, but he was known

around town as “Irish Mike”—showed her his badge and

asked if we might come in. She ushered the three of us into

a spacious and tastefully decorated living room. We all declined

her offer of coffee and she asked again how she might be of service.

“Mrs. Green—it is Mrs. Green, Jenny Green, is that right?—

Or do you prefer Ms.?” “Either way is fine,” she said,

fixing her blue-grey eyes on him. “What’s going on?”

“I’m afraid we’ve brought bad news. Your husband is dead.”

“Dead?” she said, looking blankly from one detective to the other.

I stood back and tried to match the wallpaper.

“Yes. And it gets worse. We have reason to believe he was murdered.”

“Murdered? ” She lingered over the contours of the word,

as though it belonged to no terrestrial language.

“There must be some mistake. My husband is an investment counselor . . ..

He’s . . . why would anyone want to kill him . . . he’s . . ..”

She held fast to the present tense, as though it were her only hope.

“Is this your husband?” Hannigan showed her a Polaroid photo.

It wasn’t a very flattering picture. He had shown it to me in the car.

Taken after the tide had receded, he needed resurrection even more than a shave.

She bobbed her chin about a quarter of an inch, her eyes puzzled and blurred.

“We’ll be calling you in to make a formal identification of the body,

and we can sit down for an interview then,” he said.

“Right now, the most important thing is that you not be alone.

Is there a family member or a friend nearby who can stay with you?

Someone you trust?” She nodded again.

I don’t think he noticed the furtive glance she gave me,

but I did, and it spoke volumes.

I would be happy to lend comfort to the widow.

I had some questions of my own.

**

“You weren’t really sleepwalking . . . were you . . .?

I don’t know what to call you.

Jenny? Mrs. Green, Ms. Rostand?”

Her business card had come apart in my pocket.

I tossed the two halves of it at her and snarled,

“Whoever the hell you are, I believe you owe me an explanation.”

I’d taken the hammock down for the duration of this meeting.

If I saw her thighs, righteous indignation

might take a turn toward the concupiscent.

She was sitting in a straight-backed chair,

more modestly dressed than I’d grown used to seeing her,

her hands folded in her lap, looking at me imploringly.

“Rostand is my maiden name.

Since I use it professionally, I kept it when I married.

I use Green when I sign documents.”

“You didn’t answer my question.”

“Why would I hire you to see if I was sleepwalking

unless I didn’t know whether I was sleepwalking or not?”

“Maybe you wanted to have a fall guy on hand.

What I don’t understand is why you’d hire me and lead me to a body

when you knew I’d have to notify the authorities,

whose first suspect would be the spouse. They eliminated me

right away since why would I knock him off and then call it in?

But they’ll be taking a long hard look at you.” I waited her out.

“No,” she admitted, “I’ve never sleepwalked a step in my life.

Unless I have and don’t know it. But you’re right, I was fully awake last night.”

“Then it can’t have been a coincidence that you hired a sleepwalking P.I.

and fed him a story about your own after-hours walkabouts,

a rather prurient story, one that had you engaged in sexual congress

with unknown men, and a wardrobe department that dressed you in a baby-doll.

You must have known that I was a sleepwalker, but how?

And why would that fact make you choose me to be your patsy?”

“I wouldn’t say patsy,” she said. “I knew they wouldn’t charge you.”

“You seem awfully blasé about the possibility of going away for murder one.”

“I didn’t kill him,” she said. “Nobody did. My husband took his own life.

“If the law tries to lean on me, I can prove it.

He left a note. A note which not only announces his intention

to end his life but explains why he felt driven to such extremity.

But if our efforts are successful,

you and I are the only people in the world who’ll ever see it.”

Efforts? What efforts?

“I really am a photographer, but for a few years a few decades ago,

when my first marriage ended in divorce,

I became a licensed hypnotherapist.

That’s how I could tell you were sleepwalking.

But how did you know I wasn’t? What tipped you off?”

“You sauntered.” “I sauntered? And you knew I was awake?”

“Yes. You have a memorable way of walking. It struck me

that it would have been different if you’d been unconscious.

When you’re awake, your walk suggests that you know all eyes are upon you.

How could you know that if you were in the Land of Nod?”

“Damn. I never thought of that. When I worked as a therapist,

my clients were always seated. I put them under and fed them

suggestions to help them quit smoking, or stop fucking

total strangers or give up online gambling or something.

But they stayed seated until I brought them out.

When I ran into you in The Salty Dame that night,

I was in a rather confused state of mind, angry and

anxious and despairing all at once,

not to mention half-shit-faced thanks to straight shots of tequila.

But I was still sober enough to notice that

your eyes were unfocused and inner-directed.

I had seen that look many times in my clients’ eyes.

And your facial muscles were slack. I knew right away.

But I never saw you walk. I saw you leaning against the bar,

then we were dancing and then you disappeared into the crowd.

It never occurred to me to alter my walk.

I hired you on impulse after I noticed that you were out on

the town without knowing you were there. Nice P.J.s by the way.”

“Thanks. Go on.”

“I made up the story the night before I first showed up here,

after I had returned home from the saloon and found the note.

I couldn’t know for certain, but I thought it likely

that you knew you’d been sleepwalking,

and that it would make you sympathetic to my plight.

I threw in the sexy parts because, well, because

you’re a man, and that meant you’d find it intriguing.”

She should have blushed, but instead she grinned.

The grin went well with her freckles. She looked like

a uncommonly attractive woman whose picture had

appeared on a carton of corn flakes when she was a kid.

Men have a habit of attributing a variety of virtues

to women who just happen to be beautiful: nobility

of character, kindness, compassion, forgiveness.

In a word, understanding. We think they’ll be understanding.

Was I one of those poor deluded bastards? I sure hoped so.

“Don’t tell me you’re in it for the insurance money?”

Was the ghost of Billy Wilder hovering over my case?

She laughed. “Hardly. There won’t be a payout.

“He’d been borrowing against his policy.

“He also took out a second mortgage on the house.

“The bank will own it before the month is out.

“His Range Rover is leased and the lease is about to expire.

“When I told you I married money, I should have said

“that I married a man whose money was nearly gone.

“He spent the last of it on me and a shyster.

He made very sound investments for others,

but quite reckless ones on his own. When we first met,

he had enough left to put on a convincing show,

and to court me in a ‘sweep her off her feet’ kind of way.

We had a fine honeymoon and a few good months together

and less than a year later he left me with nothing.”

“Then why go to the trouble to make it look like murder?”

“I didn’t make it look like murder,” she said. “I let it look like that.

Do you know much about the canals?”

“Exactly as much as you can learn from getting blotto and falling into one.”

“I’ll tell you a story that almost no one remembers. In the late 1960s,

one of many proposed projects to restore the canals of Venice,

which had fallen into ruin, was known as the ‘deep water plan.’

It had received approval from the city, assessments had been sent

to property owners, Mayor Bradley was on board. It was to include

access by large boats from Marina Del Rey into the Venice canals.

But a lawsuit by a Howard Hughes company, the Summa Corporation,

and a man known only as Mr. Green stopped the project.

They were able to do so because the water

flowing from Marina Del Rey to the canals in Venice

passed through the section known as ‘Ballona Lagoon.’

The property under the water was owned by the Summa Corporation.

When Hughes died in 1976, the corporation

was dissolved, removing any serious opposition.”

“Who owns the land now?”

“The city of Venice, in perpetuity. Supposedly.”

“And Mr. Green? A relation, by any chance?”

“Not of mine. But yes, he was my late husband’s grandfather.

He remains a minor, obscure figure in the historical record.

Until you begin to dig around. Mr. Green was a low-level

functionary of the Summa Corporation, really nothing more

than a flunky for Howard Hughes. As part of a complicated

corporate tax dodge, Hughes had made Mr. Green the paper

owner of the Ballona Lagoon land. It was supposed to

be temporary. But, as you know, Hughes had his fingers in

a great many pies—as well as a number of actresses—and was distracted for a time.

When the new tax year commenced, he neglected to switch

the ownership back to the corporation. Then he died and

the corporation was dissolved and everyone forgot about it.

Everyone, that is, except Mr. Green.

He hired a lawyer and spent the last two years of his life trying to

prove that he was the legal owner of the Ballona Lagoon property,

which would have given him the rights to the water flowing into the canals.

In other words, he would have controlled the housing market in Venice,

whose real estate became some of the most coveted in Southern California.

But its value evaporates if the homes are not

along the banks of properly operating canals.”

“This lawyer Mr. Green hired, would you characterize him as a ‘shyster’?

Was your husband’s grandfather swindled?”

“On the contrary, as far as I can tell, the lawyer ended up dropping all his

other clients and devoting his entire practice to Mr. Green’s case.

But the legal team of the late Howard Hughes overwhelmed him with writs and challenges

and countersuits that ended up bankrupting Mr. Green and his lawyer.

They both died penniless and embittered. But right up until the end,

they vowed to have their day in court. It was not to be.

You could say the lawyer swindled himself, but not entirely out of greed.

It’s true that if they had triumphed,

his piece of the action would have added up to a substantial fortune.

But the two of them had also convinced themselves that they were

fierce and righteous underdogs whose flaming sword could bring down the mighty.

The case became their mutual obsession. They spent their last years

together in shabby offices bent over stacks of court documents

which grew taller as their bank accounts dwindled.

They had no time for their families. I doubt whether either even noticed

when their wives filed for divorce. My husband’s grandfather

took to drink and in short order it made an end of him. His body was found

in what I believe is referred to as ‘a state of advanced decomposition.’

Shortly thereafter, his lawyer, a teetotaler, following him into oblivion,

after being struck down by a streetcar.

Since their deaths, no one else has ever pursued their claim.”

“I can’t help feeling that the word ‘until’ is about to make an entrance.”

“You’re right. Until my husband, who had never so much as met his grandfather

and cared not a whit about his doings climbed into our attic to look for

a cameo brooch which had belonged to his grandmother—he wanted me to have it—

and instead found a cardboard box full of old papers

which is how he inherited his grandfather’s obsession.”

“I’m just playing a hunch here, but I’d wager that wasn’t all he inherited.”

“No. Everything his grandfather owned, which amounted to a gold pocket watch

and the box of papers, came down through my husband’s father to him.

You can probably guess why he hired a lawyer.”

“Yes, if your dear departed could have won the case that the earlier

late Mr. Green had initiated, then he would own the land beneath Ballona

Lagoon and become one of the wealthiest men in southern California.

As matters now stand, it would belong to his wife.”

I gave her a hard, questioning look, which she did a fine job of ignoring.

“What has become of your husband’s now-clientless lawyer?”

“There’s a funny story about the lawyer. My husband had done

an internet search and learned that the first Mr. Green’s lawyer’s son

had passed on, but the grandson was still with us.

So my husband went out looking for his grandfather’s lawyer’s grandson.”

“Did he find him?”

“He did. And it turned out that his grandfather’s lawyer’s grandson had

also become a lawyer, with a lucrative practice in Century City, no less.

His firm has their choice of the choicest clients in the Southland.

Unlike my husband, he knew about the old case.

Family legend had left him with the legacy

of the two mad old men and their sad ends.

But until my husband laid the papers in front of him,

he was ignorant of the legal particulars.

He grew instantly enthralled. So my husband hired him.

And then, in the hope of making a grand score that would more than

make up for the losses he had suffered, he abandoned his other endeavors.

As you can guess, history repeated itself. The two became inseparable.

Their every waking hour was devoted to this preposterous project

and the last of my husband’s funds drained away.

Eventually, I found myself married to a pauper.

He couldn’t even continue to pay the lawyer.”

“I don’t suppose the lawyer offered to work pro bono at that point?”

“No, he allowed as how he had a living to make. He wished my

husband good luck, and departed for greener pastures.”

“Then what became of him? The shyster?”

This time she did blush, rather becomingly.

“I only used that term because it seemed like something

you should say in the office of a private eye.

“But what I believe is this: His lawyer, without mentioning it,

unearthed some new evidence confirming that the land

indeed had belonged to the first Mr. Green. Indisputable proof.

He kept the new evidence to himself, and when my husband

ran out of money, he might even have suggested

he do the honorable thing and fall on his sword.

He was, after all, facing both public and private disgrace.

I knew something was going on

when wouldn’t look me in the eye for the last week of his life.

He couldn’t meet his debts. In his mind,

he must have felt he had nothing left to live for.”

“But why? It makes no sense. If they had won their suit,

your husband would have been a rich man again, the lawyer

would line his pockets and his reputation would skyrocket.

With your husband dead, the property would go to you.

Where’s the percentage?”

“Buried in the phrase, ‘power of attorney.’

I think the lawyer formed a small corporation

with the two of them as the only officers.

They were to enjoy joint ownership of the Ballona Lagoon property.

If one died, the other would retain title to all of it.”

“You’re telling me that the lawyer, hell, the shyster,

kept vital information from your husband,

drove him to self-slaughter,

and now intends to become a one-man land-grab

that will leave him rolling in unspeakable wealth?”

“Yes.”

“And of course you can’t prove any of it, but you’d like me to . . . what?

Avenge your husband’s death? Reclaim his good name?

Help you to lay your own hands on unspeakable wealth?”

“I give you my word that if we can prove that my late husband’s

grandfather had clear title to the Ballona Lagoon land,

which my husband rightfully inherited, and which would now be mine,

I have every intention of donating it to the City of Venice,

with only one condition, that they name a canal after him.

I’m prepared to swear an oath on it.” She was dead serious.

There was a look in her blue-grey eyes that made me realize,

for the first time, that she had truly loved her husband,

that she missed him and wanted to carry on his crackpot mission.

You don’t often meet anyone who really

doesn’t give a damn about the money.

“What would you have me swear by?”

I didn’t have to think about it for long.

“By the three freckles on your left thigh,” I said.

“I believe that will make it a binding agreement.”

I may not know much about the law,

but when it comes to freckles,

I am a veritable chief justice.

**

“So: the efforts you spoke of earlier. What do you have in mind?”

“The problem,” she said, “is that we can’t make a case

against him for all the legal finagling that left my husband

cuffed to a gate in Grand Canal at high tide.

“But the police, once they’ve interviewed me and cut me loose,

will be hungry for a suspect.

I intend to give them one,

tied up with a pretty pink ribbon.

I mean to take the shyster down for murder in the first degree.”

Could I allow myself to be a party to framing a crooked lawyer

who had caused an innocent man’s death but not committed murder?

Even if we brought him to justice for the crimes he was guilty of,

he wouldn’t serve much time. White collar criminals rarely do.

He would play ping-pong for a year or two and walk.

“What makes you think I’d go along with this scheme?

It doesn’t sound as if it would add much to my own worldly estate.”

“I didn’t need to study your . . .. ” She cut her eyes around my crib,

“surroundings,”—I’d stashed the empty bottles in the mini-fridges and

cleared away all the dirty sox and underwear that had been piling up,

but the place still wasn’t what you would call tidy:

I had meant to push the Murphy bed back into the wall

but it was stuck halfway up and looked like one of

those bridges that rise to let a tugboat pass under—

“to figure out you’re not in it for the money.

My decision to hire you wasn’t based entirely on impulse.

I read up on some of your old cases.

I wouldn’t call you a champion of lost causes exactly, but you do

have a history of helping people who have nowhere else to turn.”

“Well, they paid me.”

“And I can afford to keep paying you three hundred dollars a day,

plus expenses, for one more week,” she said, “Then it’s Tap City, Daddy.”

“Well, it could be a busy week.”

**

“I have one and only one shirt with French cuffs.

I call it my drinking shirt, because I figure if I can take

the cufflinks out at the end of the night, I haven’t overindulged.”

I didn’t mention that my personal best

was getting one out before tipping over.

“I’ll be wearing it tonight. The Salty Dame,

where we met without my knowing it,

is my cop associate Irish Mike’s watering-hole of choice.

I think I’ll wander down there and hoist a few with him.”

“Try not to fall into any canals.”

“Good plan. It would be hell trying to get cufflinks off underwater.

What about you? Are you ready?”

“I think so. Do you remember the little red dress I was

wearing the first, well, the second time we met?” she said.

I nodded, secure in the knowledge that it would be time

for those in attendance to pull the sheet up over my head

when I forgot the sight of her in the red dress.

“Well, ” she said, “I have the same dress in black.

I think it’s time for the grieving widow to pay a call on the shyster.”

**

“Hey! It’s the shamus! You busted out of the tiki bar!

If they’re going to start allowing low-rent gumshoes into this place,

who knows what might happen next?

I guess I can’t hope for hat-check girls, though,

you’re about the only guy I know who wears a hat anymore.

Nice links. Buy you a drink?” “Thanks. They were a gift from

my Irish grandmother.” And while they did feature matched

miniature portraits of W.B. Yeats, I had found them in a thrift store.

I hadn’t ever met my father’s mother any more than Jenny’s husband

had had the chance to know his grandfather,

but I love making up stories about her to enliven conversations.

Irish Mike, though he adopted a hard-boiled Dash Hammett-style patois,

was an unusual kind of cop. A compulsive reader, in fact,

who had lost track of a few suspects over the years on stakeouts

when he he’d gotten engrossed in Flaubert or Flannery O’Connor.

When our drinks arrived, I said, “You having any luck with . . ..”

I jerked my head at the door to indicate the death at the sea gate.

The local press was having a field day with the story.

One inquiring reporter had picked up on Mike’s word

and the ensuing headline ran:

Financier Fished Out of Canal!

“No. The local matrons are all a flutter.

The gentry prefers it when homicides are committed in the Valley.

But so far we’re just going through the motions.”

“You don’t like the widow for it?”

“Ordinarily, she’d be in lock-up already and

need a better lawyer than she can afford.

But we know the time of death—

call it an hour one way or the other—

and at the time, she was seen by

a lot of people dancing the

night away in this very dive.”

I had to hope they’d all been too sloshed

to notice her dancing with me.

“Why do you say ‘better lawyer than she can afford’?

I thought the deceased was rolling in it.”

“Was is the operative word here. He had

recently suffered some serious setbacks.

We pulled her in and she knew all about

her husband’s misfortunes. It would have been

exactly the wrong time to make a move on his holdings.

So, solid alibi, no real motive, nothing to gain.

And, although it’s not very scientific of me to say so,

I don’t think that dame has a deceitful bone in her body,

her rather spectacular body, if I may be permitted

such liberties of language now that I’m off-duty.”

He threw back his drink and raised the

glass in the air, waving his arm around.

It might not have been his first of the evening.

“You liked her?” “I did. I wish I had something

on her so I could haul her back in. He tipped his chair

back a little and tapped his empty glass on the table.

“She’s a real woman, you know? Not one of these Instagram

bimbos you see everywhere now, with their implants and

newly chiseled noses and puffy collagen lips. And those chirpy voices!

They all sound like cartoon characters doing the nightly news.

Whatever happened to real women’s voices? Lauren Bacall? Jean Arthur?

Betsy Drake? You remember her? And that singer, Timi Yuro?

You ever hear her speaking voice? This Jenny Green, she looked right

at me and her voice was, whatayacallit? Rueful, that’s it.

A rueful contralto. A rueful contralto with a wry grin.

And all the time she was talking, she never once pulled out her phone.

That alone makes her one in a million. Her hair was loose

and she wasn’t wearing any makeup. Don’t you just

love it when a woman doesn’t wear makeup?”

The waitress, in a cowboy hat and boots

and no more than half a pound of makeup

brought us a fresh round.

He tossed half of his back in a gulp.

“You should see her legs. They’re longer than

baseball season when your team is in the cellar.”

The thought carried him a long way off, and rather

than intrude upon such a pleasant occupation,

I sat silently by his side while we each downed a

half dozen or so drinks. I threw some of Jenny’s

money on the table and made my way out.

**

The shyster’s office was in Constellation Place at the heart of Century City,

where the streets had names like

“Billable Hours Boulevard.”

I suspect the window cleaners

in these glass and chrome towers

take home more money than I will ever see.

I had never done business there, only been blinded

by the sun flashing off the skyscrapers as I drove by.

I envied whoever might have seen Jenny stepping

in the black dress out of the black Range Rover,

but it was important that we not be seen together.

I waited impatiently at my desk for her report,

flipping playing cards into a turned-over fedora.

Already, I was able to recognize her footsteps

coming up the stairs from the tiki bar.

The hammock was up and waiting for her,

a mai tai sitting on a coaster on the floor.

**

“How did you . . . put him under?”

“I started talking to him and then slowed my voice down,

speaking to him in the low soothing tones I’d been trained to use

when placing someone in a trance.

When I saw that his eyes were beginning to glaze,

I crossed my legs. Then I crossed them again.”

“Ah, the old double-cross!”

“Slowly and repeatedly, I continued to cross my legs.”

She demonstrated and then re-demonstrated the technique.

“When his limbs relaxed and his face went slack,

I was certain he had entered a deep trance.

Then I just let him talk. Would you like me to play it back for you?”

Someone snapped their fingers. “What? What did you say?

I’m afraid I dozed off for a second.”

“You were going under.” she said.

“I asked if you’d like me to play it back for you.”

“You were wearing a wire?”

“Sure. In fact, since I had it clipped to my bra,

you could even say I was wearing an underwire.

I thought you had a right to know what you were getting into.”

“Where was the receiver?”

“Right here.” She reached under the wooden island that divided

her kitchen where we were sitting and sipping dark French roast,

pulling out a mini-recorder. It must have had a super-sensitive mic.

During playback, I thought I could detect the whispered promises

of her stockings as she was crossing and recrossing her legs.

But then, I am a detective. Their voices were muted,

measured, each word spoken distinctly

in the cut-glass-decanter atmosphere of his luxurious office.

His voice declared him a self-appointed paragon of suavity.

But listening to him I felt like a seabird trapped in an oil spill.

I knew somehow that he had kept his full head of hair but secretly dyed it,

that in a drawer of his vast Brazilian rosewood desk

was a was a candy jar filled with Viagra,

and that the picture of his wife, their kids and grandkids had moved

from the desk to the drawer before this meeting began.

“I’m so terribly sorry for your loss. If there’s anything I can do to help,

anything at all, don’t hesitate to call on me. Your husband had become more

than an important client to me, more than a friend, really. A beloved

nephew might be closer to the point. Can I get you anything to drink?”

I knew it would be cognac born years before I had come into the world.

It sounded expensive just being poured in the background.

“Please tell me how I can be of service?”

“Well, to be honest, I didn’t know where else to turn. My husband always

took care of the finances. It was his area of expertise, after all. I’m a

photographer—”

“You might also have been a model,” he oozed.

“Why, thank you. It’s been a long time since a man, well,

any man other than my husband, has spoken to me that way.

But, as I was saying, I need an advisor, someone with a strong

and a steady hand who can guide me, someone I can lean on.”

She paused the recorder. “This is where I went into my hypno-spiel,”

she said. “I told him how much I admired his skill as an attorney

and how clever he must be to have reached a station of such eminence.

Then I let him run with it.” When the tape came back on,

his voice was nearly neutral in tone, no longer trying to make an impression.

It was as though he was speaking in the privacy of his own mind.

“Yes,” he said. “I’ve done well for myself, but it’s only the beginning.

You see, once I had my hands on the memo,

I knew instantly what it could mean to me.

Venice would become my personal fiefdom. By denying them the water from the lagoon,

I can shut the canals down. They’ll be bone-dry ditches and the fancy houses

on their banks will seem like so many sharecroppers’ shacks.

Then I can snap up those properties for a song.

After the escrows close, I will turn the tap back on and sell

the same houses to rich techno-ninnies who will stumble over

Hollywood royalty to own such homes. I’ll be the real estate

King, no, the real estate Doge of Venice.”

She turned the recorder off again.

“I tried to coax him into telling me some more about this ‘memo,’

but he had it locked away too tightly in his mind. He chortled over

his grand plans, and muttered about the memo. Over and over, he

repeated the word with tremendous satisfaction, but I

was unable to get anything more out of him on the subject.

I wasn’t about to snoop around his office, so I brought him

out and told him how much his ‘friendship’ would mean to me.

Then I got out of there with my virtue still more or less intact.”

“Let me turn this over to Irish Mike. We can nail the shyster for real

estate fraud, or malfeasance or at least for malpractice. It’s a confession.”

“It would be ruled inadmissible. They’d claim coercion.”

I had to admit that if she were to cross her legs in front of me

a time or two, she could coerce me into pretty much anything,

conscious or otherwise. “So, it’s murder one or nothing?”

“Damn straight.”

**

“Your husband looked all through his grandfather’s old papers, right?”

“Yes. He and his lawyer pored over them night after night for months.”

“Then whatever the ‘memo’ is, it wasn’t among those papers.

He would have been aware of it. So the shyster didn’t happen upon

it here when they were staying up nights going over that material.”

“Which suggests,” she said, “that the memo was among his own grandfather’s papers.

Although it may be there no longer.

But wherever it is, we need to find it.”

**

The neighborhood, on the seedier end of San Vicente Boulevard in L.A.,

just outside of Beverly Hills, no more than three or

four miles from the corporate Versailles of Century City,

was only a few death certificates from qualifying as a ghost town.

History and prosperity had long since passed it by.

The four-story building, constructed in the style known,

when it was new in the early thirties, as “moderne,”

had devolved over time from faux Art Deco to genuine Art Dreck-o.

Now, still in the shyster’s name, it was dated and lackluster,

nondescript and all but ready for demolition.

The elevators might not have worked for a generation.

And I doubted whether any of its offices had ever housed a computer.

But since it had stayed in the family, the shyster had held onto it.

It hadn’t cost him anything and the rents would come in regularly

from subsistence businesses: He obviously spent almost nothing on upkeep.

But, by virtue of its very facelessness, mightn’t it

be the ideal place to sequester an item of great value?

The third story door was locked but the lock

was no match for my Swiss Army knife.

Inside, the furniture wore duvets of dust.

It might once have been fashionable,

now it looked laughable, with the exception of an antique

partner’s desk which spoke of better times and higher expectations.

The wooden file cabinets were jammed with folders going back

to the forties. I went through them painstakingly and was rewarded

with lower back spasms. And it makes me nervous being

that far from the Pacific. I need sea air, my sinuses crave salt.

I was about to call it quits, when, sitting at the partner’s desk,

going through the drawers for the third time,

no longer in search of the memo

so much as some post-war hooch,

my eye was arrested by a framed movie poster on the wall opposite me

advertising The Outlaw, “The Picture that Couldn’t Be Stopped!“

“1943’s Most Exciting New Screen Star” Jane Russell,

whose bosom, thrust into celebrity by relentless publicity,

seemed to be heaving even in a still photo.

She was reclining voluptuously in a haystack,

holding a pistol in her right hand,

but her deadliest weapon was clearly her décolletage.

She might have led many a gunslinger astray

but she pulled me out of the creaky old swivel chair

and directly over to the poster. I took it down from

its picture hangers and propped it against the desk.

Taped to the plaster wall was a plain brown envelope.

And while it showed signs of puckering with age, the tape

was neither wrinkled nor cracked nor curling at its edges or ends.

It was new. Finally, I had some idea of what was going on.

**

“It’s a handwritten memo from Howard Hughes himself,”

I said to Jenny, once we’d settled down before the fire pit

on her rooftop deck overlooking Grand Canal.

She had raided her refrigerator and freezer

and provided a shaker of cold vodka martinis

and a platter of little caviar canapés, my first.

“It’s signed and dated, and shouldn’t be

hard to authenticate. It cedes the Ballona Lagoon property

to Mr. Green in exchange for ‘services rendered.’

The services aren’t specified. He was probably

the Vice-President in Charge of Procuring Starlets.

It’s possible that only Hughes and Mr. Green’s lawyer knew of it.

Mr. Green must never have seen it. I was able to dig up what

I think is called a ‘letter of intent,’ hammered out by some

mid-level exec of the Summa Corporation, stating the imminent

changeover of ownership to Mr. Green. I expect it was all the lawyer

ever shared with his client. He saved the memo for himself.

It was his hole card. Hughes was quite addlepated

in the later years of his life, and probably just forgot to take back

the ownership. When he died, the lawyer saw his main chance.

He would have been getting on in years himself.

I think he hid it behind a poster for Hughes’ most notorious venture

in the movies just to remind himself of where it was.”

“And you think the shyster found it there?”

“He must have. The poster was one of the original run, from the early 40s,

and the envelope was all but falling apart. The glue on the flap was useless.

But the tape holding the envelope to the wall was fresh.

Your shyster must have found it quite recently, read it,

understood the upturn in his fortunes it might represent

if he played his own cards cagily, and put it back where he found it.

Then he went to work on your husband’s conscience.

I think his grandfather—had not a streetcar with impeccable timing intervened—intended to do

to the first Mr. Green what the grandson planned to do to your husband,

to rob him of the rights to the Ballona Lagoon land.”

In the great cases, there is always a dark secret seeping out of the past

like tainted blood too long dammed up.

When you discover it, you’ve got the Key to the Kingdom.

Hell, you’ve got the key to the goddam highway.

**

“Okay. I’m in. I told you I would help you put the shyster away

if we found real evidence, and the memo clinches it for me.

But how, I ask myself, are we to go about it? We don’t have proof,

so we need to come up with something that looks and feels like proof.

And it must be something the shyster cannot circumvent.

Foolproof, as it were. And I have an idea that might work.

Well, half an idea, anyway.”

“Do tell.” She leaned in. She could lean in for a living.

“When I found the memo down on San Vicente,

the phrase ‘key to the highway,’ occurred to me.

It must have stayed with me because I keep

seeing keys and thinking about them.

When I’m holding the key to my woody,

it seems to be trying to tell me something.

Just this moment, I’ve realized what.

When I was drinking with Hannigan, he spoke of the case

and he was thoroughly discouraged. He told me the department

had no leads, had come up with nothing. I think he would

have mentioned it if they had found the key to the cuffs,

the ones your husband used to . . . to dispatch himself.”

“So,” she said, “You believe that if we could come up

with a convincing enough key, and somehow plant it

on the shyster and have him searched while it’s in his pocket . . .?

“Yeah. Well, I said it was only half an idea.”

“I like it,” she said, and grinned the grin that always did me in.

“I like the hell out of it. But we can’t try to fake it.

It has to be real. Otherwise, he’ll get off on appeal.”

**

“But if the cops already conducted a search for the key

both in the canal and along the banks

and came up empty, how do you propose we find it?”

“We don’t have to find it,” she said.

“Hell, we don’t even have to look for it. I have it.”

I remembered how, at her door that night,

she had grinned and shrugged and pointed upstairs,

as though she hadn’t a care in the world

rather than a husband with lungs full of water

in a canal a fathom and a half deep and only a few knots

from where we now sat sipping martinis.

She had played me so artfully

I couldn’t help but admire it.

To some, it might seem cold and calculating.

But I knew she had steeled herself to do

whatever it took to bring the shyster to justice,

though the justice would be of her own devising.

“He left it on top of the note,” she said.

“Maybe the time has come for you to read it”

**

“It is not without deep regret,” I read, written out in flowing

longhand with a fountain pen. “that I have come to this decision.

But the fates have ruled against me. I find myself utterly impoverished,

and unable to further pursue what I believe to be my rightful inheritance.

I am determined to excuse myself from this world before I can cause

even greater sorrow to those I hold dear. I am going out into the beautiful autumn night

to cuff myself to the sea gate and there await the rising tide. Toward that end,

but fearful of losing my resolve in the eleventh hour, I am closing one of the

cuffs over my left wrist even as I write this. The other I intend to clamp to

the gate. But I am leaving the key to the cuffs here with this note.

Once the second cuff closes, there will be no turning back. My beloved

wife, who has done her utmost to dissuade me from actions she finds

foolhardy and deplorable, is still young and beautiful.

I hope that she can find happiness with a man less unbalanced and,

as I shall soon prove, self-destructive.

I have chosen the spot where I will subtract myself from existence for

symbolic reasons. It was at the sea gate that I had hoped to reverse my

fortunes. Instead, I will say farewell from there to this life with a heart

which, though troubled, has never stopped loving my dearest Jenny.”

It was signed simply, “Andrew Green.”

It may have been a tad melodramatic, but from where I was sitting,

there was no doubting its sincerity.

**

I had been stumbling through my days, terrified of falling asleep.

After my midnight encounter with my client, who knew

what kind of lunacy might ensue were I to sleepwalk again?

I could go out and play Lithuanian hopscotch with those derelicts

I’d seen down on San Vicente hauling enormous trash bags filled

with empty cans over their shoulders like so many Santas from Hell.

There were ex-wives out there, gangbangers, Amway distributors!

But I was growing desperate for heavy rest.

I, too, had begun muttering aloud about the memo, laughing at nothing,

talking to people who had been dead for years.

Maybe if I put myself down, with extreme prejudice, my body

would know better than to lurch up

and go traipsing out into the underworld.

I found a gigantic mason jar in a cupboard,

and mixed the world’s biggest knockout concoction:

A full bottle of Nyquil, one of Stoli, an old and

probably expired Quaalude, a cruet of laudanum, and just

a pinch of Ecstasy in case things got bumpy. Goodnight, Irene.

**

I awoke at dawn, my hands jammed in the pockets

of my pajamas against the cold, completely alert,

standing on the bank of Grand Canal, a soft toss

away from my client’s house. My clothes were dry,

so I hadn’t gone into the water. I felt distinctly . . . happy.

It took me a minute to recognize the sensation,

which I attributed it to the lingering effects of the Ecstasy.

I tried trailing my fingers back and forth in front of my face

to see if they left little vapor trails, an old trick of psychedelic adherents.

Results inconclusive. It might have been the dispersing of mist from the canal.

My head was a cineplex of strange images and what I took to be dream-fragments.

Did I dream when I sleepwalked? How could you tell? At least,

I seemed to have sleepwalked. I was pretty sure I hadn’t leapt out of bed

and gone bopping out for a latte. By raising my eyes, I could see that I was

wearing a forest green brushed velour fedora from the Shlock Shop in North Beach.

In my crib, I keep double-ranks of mannequin halves in two long curving rows,

half are the lower halves, set upside-down with legs waving in the air,

the others upper torsos which stand on low pedestals.

Together, they constitute my hat-rack.

All the hats are fedoras, with the exception of a couple of Dodger caps

which I wear when my team is on a winning streak.

I had gotten out of bed, walked to the mannequin halves, selected

my hat for the day and departed. I wiggled my fingers in the pockets.

No key, either for my woody or for the downstairs

door of Paradisacs, the current name of the tiki bar.

The left pocket held a Skee-Ball ball.

So I must have slid down the stripper pole. It was far easier to climb up

the palm tree but exit via the pole. Occasionally, passing beach babes

would perform spontaneous routines on it. Once in a while one would

actually strip as the sun was rising and they were returning home from a long night.

If I was up early, I might drop down a mango by way of an ovation and a tip.

Very slowly, as if a movie were assembling itself inside my head,

scenes returned, but in a jumbled order: a man out walking in one of

those absurdly expensive outfits that people now buy to walk in. It was

confusing because he looked like I had pictured the shyster looking

when in fact I had only been hearing his voice on Jenny’s recorder.

I didn’t know if I had ever met this man before, or even if I had met him now.

But he had greeted me jovially, a fellow morning pedestrian on the pier.

I wiggled my fingers in the right-hand pocket and touched a sharp edge of paper.

When I pulled it out, I found a business card. It read:

“Beaumont, Craven, Gillespie & Strunk, Attorneys at Law.”

Beneath that, in raised lettering was the name Brian Halpern.

Bonny had told me the shyster’s name. I couldn’t recall it at the moment,

could barely remember my own. But it wasn’t Brian or any of these others.

After this semi-recollection, things got even blurrier. I may have bumped into

some of the usual, which is to say highly unusual, street folks of the boardwalk:

A flamenco guitarist with his pet iguana, a very old woman looking

for the Russian Tea Room—had I told her she was on the wrong coast?—

a few hookers who must have thought that since I was in my pajamas,

I must be ready for bed, so . . . In other words the irregular miscellany

of the footloose, the fugitive and the only slightly

deranged citizens of the patch I call home.

Had any of what I thought I remembered ever happened?

Or was it all composed by one of Morpheus’ trusted lieutenants,

the thoughts of other walkers impinging upon my consciousness

and the resurfacing of older memories from my earliest days?

For that matter, was the world in front of me—the one verified by my senses—

the world we all know, was it really there?

Or was that world, our world, itself asleep and awaiting an awakening?

None of these questions made any sense,

at least they made no sense to me when I was awake.

A touch on my shoulder almost prompted my second tumble into a canal.

“Hey,” said Jenny, softly. “I saw you out here and figured

you could use some coffee. I added a tot of Irish.”

This time it was she who gestured at my outfit.

“You were sleepwalking?”

“I must have been. It’s too early for Pilates.”

“I’m glad your subconscious knew to steer you here.”

“Me, too. I like your coffee.”

“You wanna come in?”

“Sure. I’ve only seen your kitchen and the rooftop deck.

You can give me the entire tour.”

It was on a corner lot (if you can call a bend in a canal a corner),

at the confluence of Grand Canal and Coral Canal.

There were three bedrooms, each with its own bathroom and fireplace,

each with enough closet space to shelter a small family.

Each bathroom had en-suite baths, Japanese lounging pools,

rainfall showers and marble counter-tops, as well as its own private deck.

There was a junior Olympic-length indoor pool, with jacuzzi.

And there were, of course, spectacular views from every

conceivable vantage point, as though the world had been

built to accommodate the house rather than the other way around.

Since her husband was dead, there was no point in envying him,

and the same went for her since she was about to be put on the street.

So I was free to enjoy it for its own sake, as a set, so to speak.

We walked around, she pointed out architectural features and

paused in front of a handful of her photographs. I know nothing

of photography, but she unquestionably had a good eye,

and the born snap-shooter’s instinct to press the button

an instant before something happens. Otherwise, you miss it.

We had ascended the custom wood stairs and

were sitting at the indoor wet bar on the third level.

She had made a Bloody Mary for me and a mimosa for herself.

It was about eight a.m. The sky looked like it had grown

out of the palm trees on her property,

a tingling blue with earth and sand and chlorophyll mixed in.

I handed her the business card.

“This isn’t the shyster, right?”

“No,” she said, “that’s another member of his firm.

Where did you get this? Did you meet him?”

“I don’t really know and can’t really say,” I said.

“I think we crossed paths this morning on the pier.”

If I’d been a cop, I could also have been my own suspect.

“Well, if you did, it qualifies as a rather bizarre coincidence,” she said.

“This Halpern fellow is in competition with the shyster

for a partner’s position that’s opening up over there.”

“Don’t tell me you met him in the elevator in Century City,

stopped the car between floors and started crossing your legs?”

“No, I overheard the story when Andrew

and the shyster were working on their case.

Making partner is, as you know, a big deal in those firms.

It’s the attorney’s equivalent to being granted tenure in academic circles,

only, of course, you make a lot more money.”

“Why on earth would he have given me his card?”

“Good question. But I can’t think of anyone who’d

be more eager to pin a murder rap on the shyster.

Maybe you were talking out of turn while sleepwalking?”

“Is there any other way to talk when you’re sleepwalking?”

“In his note,” I said, your husband mentioned

something about ‘those I have caused sorrow.’

You, obviously, were one. I was wondering who else.”

“That’s kind of a sad story. I have a daughter named Lilette

by my first husband. Lilette was living with Andrew and I

and there was a terrible quarrel between the two of them.

She decamped and moved to Florida to live with her dad.

Just took off. Andrew never forgave himself.

And Lilette still won’t talk to me.”

“May I ask what the quarrel was about?”

“I don’t see why not. Andrew wanted to adopt her,

and she is fiercely loyal to her father.

The thought of having anyone else take his place

repulsed her. She thought her dad should have

joint custody, and she should spend half the year with him.

I tried to take both sides, but I failed miserably. She got it

into her head that Andrew meant more to me than my own child.”

“How old is she?” “She just turned sixteen. If I were to pursue the matter

through the courts, I’m sure I could have her escorted

back to California, but she would never forgive me.

She’d end up spending nights on the boardwalk or

under the pier. Then, when she turned eighteen, she’d

say goodbye to the Golden State and go back to the Gulf coast.

Andrew made himself out to be more of a villain

than he deserved. But that’s what he was referring to.”

**

After we parted, I took a long walk, just to see

what it would be like to walk when I was awake.

I felt as though I’d been living in a brochure for the past half an hour.

I went down to the Beach, rolled up my pajama pants and waded into the surf.

It put me in mind of the old wino in Jenny’s photograph

and made me feel like I should have a walking stick and a goat for a sidekick.

I sank to my knees and scrubbed my face with sea water.

**

I had known a few public defenders over the years,

upstanding men and women for the most part,

but never a lawyer for a prestigious law firm.

I knew that I didn’t belong in Century City,

where security cameras outnumber the birds and martinis cost fifteen bucks.

I clung stubbornly to the conviction that I needed to stay on my own ground.

So I kept walking, forgetting to eat, I even forgot to drink,

wearing my pajamas in case they would trigger memories in anyone I ran into.

I spent a whole day asking people if they’d seen me the night before,

tailing myself while talking to myself, trading some of my client’s money

for pitiful scraps of information.

Plenty of people had seen me, some were even pleased to see me again.

Not a one could tell me as much as the Skee-Ball ball in my right-hand pocket.

The kid at the arcade, kicking a hacky sack around in front of the counter,

said I looked familiar but couldn’t place me from the previous day.

I ended up back at same spot along the railing on the pier.

“Say, I haven’t seen you since early this morning. How have you been?”

“Good evening, Mr. Halpern, is it? A long strange day, I must say.

I’m afraid my personal fog didn’t burn off until about noon,” I said.

“Would you be kind enough to remind me of why I have your business card?”

“Certainly. We met right here. I often take coffee here of a morning

and watch the sea. Then I make the same stop on my way home.

This morning, we hadn’t spoken for about fifteen minutes when you

launched into a rambling, somewhat incoherent story.

As a member of the local bar, I was able to recognize after a while

that you were talking about about the alleged murder

at the canal a few days back. Then I gave you my card.”

“It’s not so alleged if you happen to be the murder victim,” I said.

“No,” he said, shaking his head and laughing. To his credit,

it wasn’t a country club chuckle which would have signified

his station above such sordid affairs, but a laugh of genuine sympathy.

“Indeed not. Did you know the deceased?”

“Never met the man,” I said, more or less truthfully. “I tell you

what. You won’t be surprised, given my ensemble, to hear

that I’m out of pocket at the moment. But if you could

loan me a dollar, I will give you, as security, this Skee-Ball ball,

which was left to me by my Irish grandmother on her death bed,

and meet you here tomorrow morning to return the money.”

He looked both bemused and intrigued, but reached into his

back pocket, hauled out his wallet, plucked out a single,

and handed it to me. “Thanks. I’d like to hire you.

Here’s a dollar to seal the agreement. See you tomorrow.”

**

At our next meeting, the following morning, I was

somewhat more respectably dressed: black woven trousers,

a long-sleeved pale blue Irish linen shirt, good sandals,

silk socks and one of my favorite fedoras. In my pocket

was the key to the cuffs. Lawyer Halpern and I now enjoyed

attorney-client confidentiality. No such guarantee

extended to Jenny. It was important that I step

carefully here. “Though the late Mr. Green and I

weren’t known to one another, I do have an interest in the . . .

disposition of the matter. I believe one of your

colleagues represented him, is that right?”

“Yes, I think so.” He mentioned the shyster’s name.

“Did you bring the Skee-Ball ball?”

“Of course. Otherwise, how could you know

whether I was operating in good faith?

However, I must say that your grandmother,

may she rest in peace, must have been a trifle daft.”

“She was struck by lightning. She lived,

but was ever a little haywire from that moment on.

I have something to offer you in exchange

for the ball. I think you’ll find it a fair trade.”

I handed him the key to the cuffs, which he

accepted without a word, only nodded, handed me

the ball and went back to blowing on his coffee.

I returned the dollar I owed him,

wished him well of the sea

and never set eyes on him again.

**

Back at 2218 Grand Canal, Jenny and

I were going over my expense account.

Lawyer Halpern had behaved in

accordance with our hopes and expectations.

Nothing fancy: all it took was a high-end

escort service, an obliging call girl, and an

anonymous tip to the cops. Simple really.

She had even left the door open

to make it easy for them. The shyster

had protested mightily and thundered

about the repercussions after the

key to the cuffs was found in his jacket.