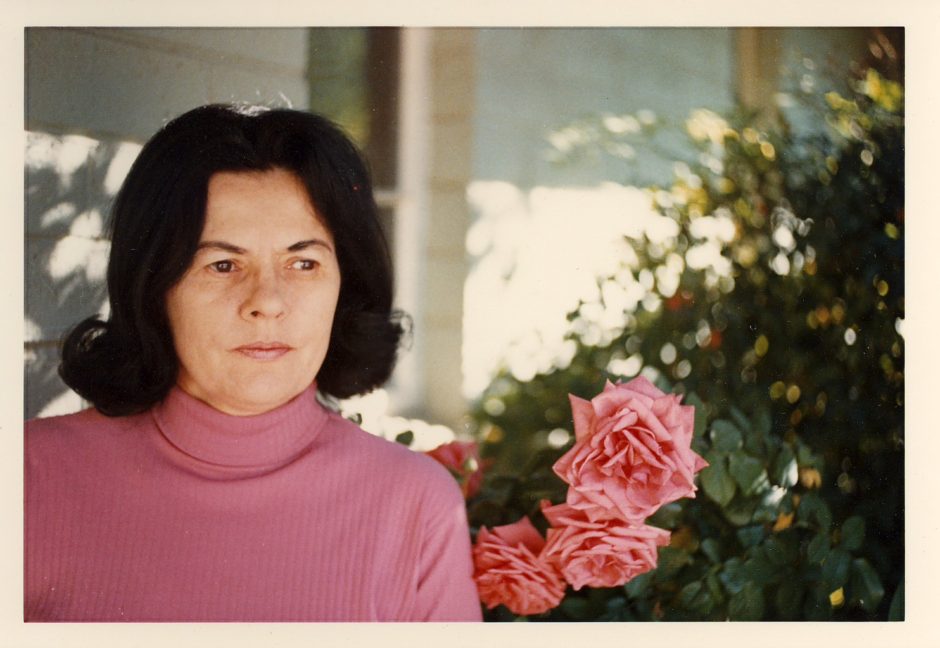

I was named for my mother, Jacqueline Rochester (1924-2010). I suppose in some way she hoped I would continue her legacy as an artist and while I did not paint – that legacy was passed on to my brother Gregg – I did become a writer. There are a number of legacy gifts my mother gave to me and her family, too many to recount here. But it is Mother’s Day, the day each and every one of us can invoke the truth that we have only one mother and she is deserving of our acknowledgement today.

I was named for my mother, Jacqueline Rochester (1924-2010). I suppose in some way she hoped I would continue her legacy as an artist and while I did not paint – that legacy was passed on to my brother Gregg – I did become a writer. There are a number of legacy gifts my mother gave to me and her family, too many to recount here. But it is Mother’s Day, the day each and every one of us can invoke the truth that we have only one mother and she is deserving of our acknowledgement today.

There is a well worn phrase I think of often when it comes to artists, whatever their medium: Many are called, but few are chosen. My mother was called and she chose, big time: she painted with vision and imagination and fervor. It was no hobby  for her, it was her raison d’etre and her entrepreneurial business. How she made her living. She was an artist and, without it being apparent, a businesswoman who sold every single canvas she painted. She always had gallery representation, usually several. She created a line of clothing, greeting cards; she sculpted and made bronze courtyard fountains. Even today you can see her art for sale across a number of websites on eBay. Click on the pix for a larger view.

for her, it was her raison d’etre and her entrepreneurial business. How she made her living. She was an artist and, without it being apparent, a businesswoman who sold every single canvas she painted. She always had gallery representation, usually several. She created a line of clothing, greeting cards; she sculpted and made bronze courtyard fountains. Even today you can see her art for sale across a number of websites on eBay. Click on the pix for a larger view.

Yeah, I’m proud of my mother and her work. She went through many different stylistic periods, but always seemed to be in sync with the times – and herself. I remember her as inspiration: to be the best you can be, and never to rest on your creative laurels. We had a memorial service for her in 2013 at the Dahl Arts Center in Rapid City, South Dakota, and I was pleased to learn how many people remembered her and told me an illuminating story about her. I told the story about the time I’d gotten a henna tattoo for her birthday.

in sync with the times – and herself. I remember her as inspiration: to be the best you can be, and never to rest on your creative laurels. We had a memorial service for her in 2013 at the Dahl Arts Center in Rapid City, South Dakota, and I was pleased to learn how many people remembered her and told me an illuminating story about her. I told the story about the time I’d gotten a henna tattoo for her birthday.

I said she was a painter and I a writer, but she wrote, too, although just for a few years and mostly articles for newspapers and magazines. She set her typewriter to fiction a few times, and what follows is the result with a few more of her artworks inserted here and there.

THE CONFORMISTS

“However many bad men did my gun-slinger wipe out today?” he asked, throwing his middle child aloft.

He had just eased himself from his suburban automobile in the drive, and shed his suburban coat in the entry of his suburban home. Greg Alan conformed exactly, knowingly, and quite willingly to a million other fathers returning from the day’s walnut-paneled jungle. He raised his voice to his capri-trousered Susan in the kitchen, “What sort of creatures are the new neighbors? And make mine very rare!”

They were completely out of very rare tuna-fish. “The people next door drive a middle-priced car, have the customary type of children, and she’d wear a standard size twelve mink, although I doubt if hers has materialized yet either. They’ll fit Dover Drive very nicely, Greg. More of the clan.”

Greg and Susan gathered their young about them, closed the drapes to the world outside, and wrapped themselves in the warmth of each other and their Monday tuna casserole.

“I’ll have a little neighborhood coffee for her when’s pulled ends together,” Susan mentioned later. She had an unusual feeling about the new family’s arrival. The Cape Cod house next door had been empty; a realtor had shown it from time to time, and then suddenly one morning they were there; children playing on the walk, draperies being hung, family sounds and movements. New occupants usually arrive with the solid assistance of the orange moving van, in daylight hours.

Greg had mentioned at breakfast that morning that his sleep had been disturbed. “Nothing earth-shattering,” he had said. “Just a dull thump outside and flash of reflected light across the bedroom ceiling,” and then he had drifted off to a busy junior executive’s dreamless sleep. A row of celery-stalk poplars divided their yards, discouraging any investigating by a man too tired to bother anyway.

Susan performed all the little welcoming niceties not yet out of style on Dover Drive. A pan of hot rolls, directions to the shopping center, a list of the best cleaners and dentists, a later dinner invitation.

Susan liked Margaret Shaw. She found her stimulating, refreshing, and only in the hidden recesses of her mind did she file the tentative thought, “Unique, not completely one of us.” It takes time to know another woman, another family, by heart.

Knowing Margaret and Sam Shaw kindled the Alans’ interests, for a family is bounded to its habitat, no matter how active and diversified their individual lives. The homefront remains the hub of activity, and in these new neighbors the children found friendly, eager combat, and Susan and Greg could call an instantaneous “as-you-are” bridge game. Greg and Sam occasionally abandoned their power mowers and safaried themselves to the golf course.

“He shoots a solid game; consistent,” Greg reported at home. “Can’t quite get next to him, but it must be my nine-to-five mental block. He talks solidly of business, the market. Has an amazing grasp of the world’s crises. Bright fellow. Doing genetic research at the university, I understand.”

The two men’s leisure hours again became mutually engrossing when they discovered a common interest in the versatilities of their hobby tape recorders. Greg noted with eager interest the vast library of tape cans in the Shaws’ collection. The sounds of living surrounding them became fair game for their “little-boy” competitive game of recording the newest, most imaginative sounds. Who before them had caught the rhythmic grinding of the kitchen disposal, the uninhibited, scrambled words of a child’s sleep-talk, the jungle of sounds of the Siamese cat. It was an entertaining game, leaving little time for fireside chats and soul-searching. Sam and Greg grew no nearer to knowing each other, but who did in their commuter existence.

Susan drew Margaret into her circle of friends and activities. Margaret’s eager interest sparked when Susan suggested they attend an evening child psychology class at the university together. Her thirst for knowledge beyond the call of domestic duty was apparent. Still she glowed in the functions of domesticity.

“She is so flawless, Greg, so typical. Her clothes, her attitudes, her children, all so, – – Americana. She’s really, well, perfect. I suppose I should instinctively hate her, but I can’t. With all this darned perfection she is so eagerly childlike in her interest in us, our family. She seems aware of everything I do.”

She had decided not to tell Greg that she felt like a test tube in the Shaws’ laboratory.

Summer cottons wilted and the bright woolens and fall suits looked chic again. Margaret Shaw’s first luncheon was a lovely affair. Naples yellow bouquets of mums gave her chintz living room a van Gogh look, the silver caught soft golden lights, the food was properly gourmet. As guests departed Susan felt comfortable enough in her relationship with Margaret to help herself to her wrap and bag in the guest bedroom. As she checked her makeup, a minute object on the dressing table caught her attention. Intricate beyond belief, it appeared to be some sort of timepiece. The many facets of its construction, and the force which propelled it were beyond Susan’s comprehension. She stood transfixed, lost in time and space for an undetermined moment. Somehow she sensed that this tiny machine regressed to a time before time, and reached out to a span beyond space. A fear of the unknown webbed about her, the object seemed to have too much to tell, and its intricate perfections suddenly grew grotesque. Then Margaret was in the doorway, a trapped look beneath her composure, and Susan hastened to a safe subject.

Routine ran over the Alans, and the timepiece affair dropped into the oblivion of forgotten incidents. The two wives again sought each other out for momentary recesses from their worlds of children and office-bound husbands. They exchanged small talk and minor crises.

Margaret’s face was colorless the morning she rushed into her colleague’s kitchen, asking Susan to examine Janet, her eleven-year-old. Susan hurried between the houses, with empathy for Margaret’s maternal panic.

“Relax, Meg,” she breathed, unleashing her own tension. “It’s only measles. She has simply been blessed with the sixth grade’s best attention-getting status symbol.”

Margaret Shaw still stood, white and frozen. Dazed, she couldn’t seem to accept this error of nature. “Yes, I knew, I knew. They said ‘disease,’” she whispered softly. “But not my Tia, Janet, my Janet.”

Susan tried hopelessly to reassure this friend, who until now could never quite let her look within. “It will only be for a short time,” she soothed. “They disappear fast.” But Margaret’s child had suffered an ugly blight, an imperfection. She couldn’t seem to reach her, make her understand. She dialed the pediatrician.

It was ten days later, the end of Janet Shaw’s confinement period when the bakery’s delivery man announced, “They’re gone, Mrs. Alan. Mrs. Shaw didn’t tell me to cancel her regular order….”

The house was empty, the furniture gone, no forgotten cycles. They had gone as quietly and nocturnally as they had come to Dover Drive.

The bakery man was retracing his steps up the walk. “I nearly forgot, Mrs. Alan. Found this by the poplar trees on the back patio. Maybe Mr. Alan can make something of it.”

Susan placed the sliver of brown recording tape near their own machine. She had to digest their absence; she had to try to press the pieces together. She couldn’t take this final chapter of the Shaw family without Greg. This was too unreal for their substantial niche in suburbia.

Greg rewound the length of tape onto a spare reel, slipping the disk on the spindle of his machine. He adjusted the volume…

“Leader ORB, Project G reporting. We have completed assignment Raoul, research area 74NR, on Earth species, suburban dwelling area. Our team, simulating a standard planet Earth family as infused in three-year preliminary laboratory study, reports the follow data: There appears to be a definite pattern of conformity….”

Here’s to your mom and mine today. Once a mother always a mother, and we only get one.