Part 2 of the Epic Poem about a Los Angeles Private Eye

If you’ve already read Part 1, you’re probably eager to read Part 2. If you haven’t read Part 1, then you oughta. Then you’ll want to read Part 2, because before you can finish it, next week we’ll publish Part 3.

The Life of A Private Eye

a Noirvelette

by

Michael Larrain

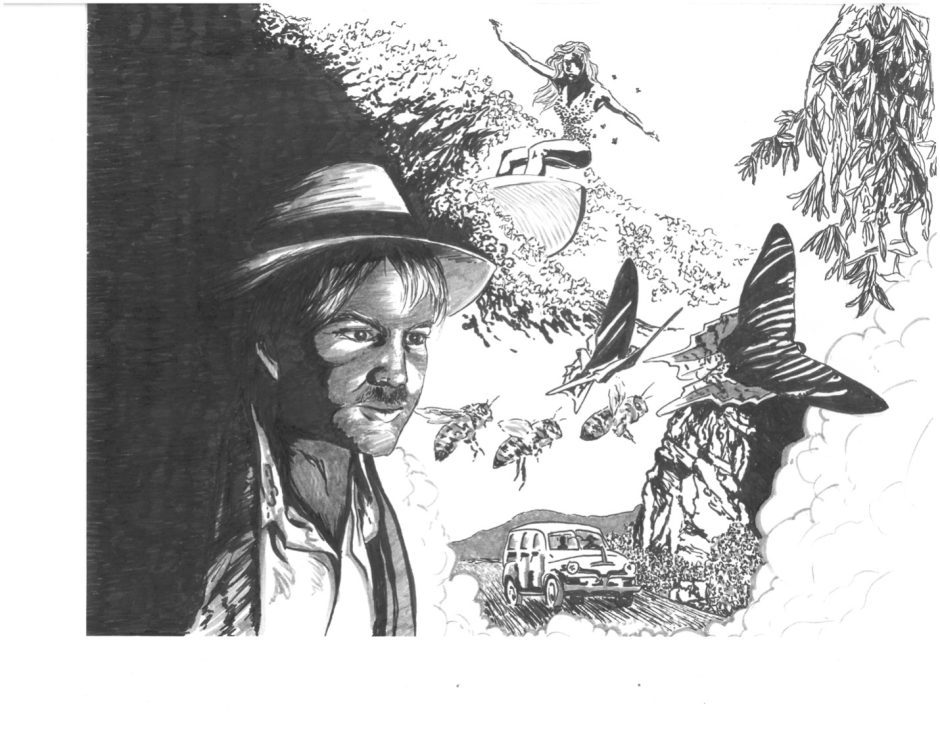

Original Artwork by

Katherine Willmore

for James Crumley, in memoriam

Part 2

How could I be dizzy

if I didn’t exist?

was my first question.

I was asleep one moment

and the next being carried on a sedan chair

through tall rustling cornstalks

by even taller women’s

beach volleyball players

whose legs went straight to the penthouse.

When their shoulders touched the corn,

it turned into salt water

and they were wading in tossing waves,

infinitesimal moths

pulling the sea this way and that.

For once I didn’t want to go back to bed.

I knew I wasn’t dreaming because all

the women in my dreams are women

I have known, or a composite of

features and qualities belonging

to women I have known. And I had never

seen any of these girls before. I don’t even

follow women’s beach volleyball.

The sedan chair changed

into one among many boxcars,

all rusting and salty

with rails curving off to the horizon,

the women’s beach volleyball players

lounging within, telling stories,

laughing and singing old songs,

warm and brown and

twirling the tassels of the corn

coyly around their fingers,

even as we traveled over the sea.

Their hair took the light

as cherrywood does oil

when they leaned over in unison,

pouring barrels of blood into the sea,

as if to revive it from a fainting spell.

The corn responded magnificently,

shooting through the roofs of the boxcars

and violating the sky, all green

and blue and yellow and blue again.

I didn’t mind that the women’s beach

volleyball players paid me no mind.

We were in separate tenses, that was all,

occupying the same space

in different regions of time.

But where were we headed?

Who was my client?

Would I ever be paid?

I needed answers and I needed them later.

When discussing time travel,

no one ever mentions

that while you may be lost,

your luggage never is.

Thus my trusty satchel was riding on my shoulder.

I rarely knew what was in there,

but I always needed whatever it turned out to be.

This time, I came up with a tangerine,

a magnifying glass and a fountain pen,

but not a clue as to my destination

or what awaited me there.

I felt a warm little buzz,

like the earth when a dog pees on it,

and realized it was the equivalent

in this form of transit

to the cord overhead on a bus

you would pull to say you

wanted to get off at the next stop.

Stepping down out of the boxcar,

I thought, If non-existence had

decided to take me out for a spin,

I certainly couldn’t complain

about the taxi service. I was

sitting in a sparsely furnished office

in some sort of corporate headquarters,

surrounded by a lot of glass and white-painted

metal beams, wooden desks and

color-splashed paintings on the walls,

a great many potted plants flourishing in the corners.

Two young men, one in jeans and t-shirt, the

other in t-shirt and biking shorts,

both in low, clunky-looking hiking

boots sitting across from me.

In the course of our conversation, neither of them ever

looked me in the eye, preferring to stay focused on

the screens of their phones and tablets. Occasionally

they would look at one another, their eyes passing

notes I could not decipher. “Have I been abducted?”

I asked. “No,” said the one in shorts, “We wanted to

talk to you about movies. We heard you like

movies. And we want to offer you a job. Coffee?”

“Sure. Black, with a splash of Irish.” God knows

I needed the work, so I decided to hear them out.

“I’m sure you’re familiar with the history of the movies,”

said the one in jeans, “but just to recapitulate:

Decades ago, people used to walk or drive

downtown, to the Bijou or the Pantages,

when, on Wednesday, the feature changed.

There was usually a second feature, a B-movie,

cranked out by the studios to accompany the A-feature;

a newsreel, a cartoon for the kids.

Then television came along.

Folks would lie on the sofa and

await the coming of The Late Show,

or the Late Late Show,

movies broadcast with commercial interruptions.

You looked them up in the TV Guide,

and waited for them to come on. Then came cable,

VCRs, DVDs, then HBO and its cousins, who,

for a price, would send you movies without commercials.

Then came streaming. You were no longer tied to your TV set.

You could watch movies on whatever device came to hand.

And then came endless variations on that theme.

And there the matter remained,

until the two of us developed the next step.”

“And I’ll bet you’re just dying to tell me about it,” I said.

“We wanted to make a quantum leap forward,” he explained,

“and devastate the competition. The technology we had in mind

was so advanced that it makes the current models

look like Victrolas or hand-cranked telephones.”

He took a deep breath. “In short, our plan was to enable

people to watch movies projected within their own minds.”

“What a nifty idea,” I said. “But we already watch

movies in our minds. It’s called “dreaming.”

“It’s funny you should say that,” he said. “Because

the dreaming process offered us a way to make it possible.

“We were having every kind of trouble imaginable,

Installing the software for the program we call

‘Head Trips.’ Our first idea was, using a half-dozen

volunteers, to place it in the tissue of the brain,

in the tracks, as it were, of the dreaming process,

following the synapses and limbic switches

and overlaying them with phantom duplicates.

We weren’t trying to interfere with the subject’s dreaming,

you understand, or to replace it, only to use

the neural pathways to create a sort of corollary, or

tributary to the nocturnal activity of the subconscious.”

“Hold on,” I said. “It occurs to me that you couldn’t watch movies

in your head while you were driving, to name one obvious problem.”

“Of course.” he replied. “We took such thing into account.

A subject, or client if you will, could only view movies,

or cable episodes, if his eyes were closed. And only if he

or she were awake. At no point was contact permitted

between the waking and sleeping states.”

“Is it possible that something went wrong?” I asked.

“I’m afraid so. We had to allow our first half-dozen

test subjects to go about their daily lives as usual.

Otherwise, the experiment would be hopelessly flawed.”

“Where do I come in?” I asked him, stalling

for time before I summoned the women’s

beach volleyball players to give me a lift home.

“I’m afraid there were some unintended

consequences resulting from the installations.”

“What happened?”

“What seems to have happened is that

the software and the dreaming process

began to coincide. And the built-in

fire walls separating movies and dreaming

began to disintegrate. The subjects started to grow

psychotic. And their dreams started manifesting

during their waking hours. One poor man, while

breakfasting with his family, didn’t even notice

that a steady stream of ants was emerging from

his mouth, ears, nostrils, eyes. He just kept

spooning in Honey Nut Cheerios and chatting merrily away.

The others were even worse. We had to pull the plug

and try to find out what had gone wrong.

But we were also obliged to remove the software.

And, as with many kinds of cranial surgery,

there were some post-operative side effects.”

“But the subjects lived through the surgeries?”

“Oh, yes. One is in a medically induced and supervised coma,

one is sailing around the world on a small raft, one

has been imprisoned after going on a shooting rampage,

one is in a Buddhist retreat and the fifth, oddly enough,

has just been named the new head of the CIA.”

“Wait. Didn’t you say there were a half-dozen

test subjects? What happened to the sixth?”

“The sixth was the only woman in the group. She

got wind of what was up, apparently didn’t want

to be brought in and made her escape. She’s at large.”

“And you want me to find her. But why me?”

“We also heard that you had worked what might be called

‘The Third Side of the Street,’ before,” he said. “And

we don’t know what she’s capable of. You must

understand. Until now, no one’s ever been in this state

of mind. No one on the loose, that is.”

“I can’t help wondering how I came to be here,”

I said. “The mode of transportation.”

“We thought you might enjoy being the first

person to try out our new “Limbic Limo App.” It’s

based entirely on the passenger’s own fantasy life.

A happy, if accidental, byproduct of our Head

Trips research and development. In truth, a car

service picked you up and delivered you here.

All the rest was provided by your own imagination.”

“What can you tell me about her?”

“Not much. She calls herself Nadja Akhmatova,

she’s in her mid-thirties, I think, and no man

who’s seen her will ever forget her, or want to.

She told us she was a theoretical physicist

and had recently undergone a brutal divorce.”

“Do you have a picture of her?”

“Only this one.” A Polaroid, taken in a

corporate cafeteria, her head thrown back, laughing.

I ventured a guess that she was Ukrainian,

with maybe an ancestor or two from Tahiti.

Seated, her lustrous black hair nearly touched the floor.

“I get a hundred and fifty dollars a day,” I said,

“plus expenses, which, in this case, I think

should include . . . unlimited taxi service.”

**

A generous advance and my signature

on a non-disclosure agreement later,

I was back on the street. Or rather,

back in my old sedan chair, the women’s

beach volleyball players sauntering me along.

I noticed that a few improvements had been added.

A drink holder, for instance, along with a drink in it.

The imagination is a wonderful thing.

My chauffeurs were the same tall, blonde, long-legged,

small-breasted beauties I remembered from my maiden voyage,

products of Scandinavian and Californian upbringings,

with the exception of a lone brunette.

The others were in the scanty bikinis

common to their trade, and sneakers, but she wore

flimsy harem pajamas, woven, open-toed sandals, and a veil.

I knew the path we were on, about a third

of the way up the Kalalau Trail on the Napali coast

of Kauai, a few miles west of Hanalei,

above my favorite snorkeling spot at Ke’ei Beach.

A few hikers trudged by us, staring fixedly at their phones,

while surrounded by some of the most spectacular

scenery on earth. I felt as though I were taking

advantage of the light, not in the sense

a photographer would use the phrase,

but as though I were compromising

the light’s original innocence,

and lemon-flavored electricity

went tearing through my veins.

It bothered me a little that I hadn’t given

any instructions to my chauffeurs

and had no idea of where we were headed.

**

The women’s beach volleyball players had dispersed,

all but the brunette, who must have been a fellow traveler.

She had changed her clothes and now,

in startling contrast to our surroundings,

was wearing a navy blue business suit,

shaped to show that she meant business,

a faint white pinstripe guiding my eyes

from her shoulders to the hem of her short skirt.

Under the suit she wore nothing but an air of indolence.

Hardly the ideal outfit for island hiking.

But when I looked around, I noticed that we were seated in a booth at the Hamburger Hamlet on Little Santa Monica in Hollywood.

Her glossy black hair was piled up on her head,

and held in place by long jade pins.

Leaning forward, she said, “I’m Nadja,”

crossing her legs very slowly,

sharpening them as a weapon

against ennui, indifference, despair,

and paused, as though recording

the sensation of my eyes upon her.

I couldn’t stop looking, unless I stopped

breathing, couldn’t stop hoping

for the chance to keep looking.

Could barely breathe but couldn’t help hoping.

Couldn’t stop believing in what I was seeing.

All of her clefts and cleavages

were like dark little culverts

where shadow might change into flame.

I wanted to place the tip of my index finger

upon her philtrum, that soft groove

connecting the base of her nose

to the border of her upper lip,

which looked as though it had been cut by

many years of French-inhaled cigarette smoke.

“Since you’re looking for me, I thought we should talk.”

Her voice was low-slung and insinuating,

as though filtered through a silk stocking.

“You’re certainly making my job easy. I expect

my clients would appreciate it. They’re worried about you.”

“Heckle and Jeckle? Those two guys wouldn’t

add up to one non-entity,” she said. “It’s worse

than if they were brilliant but mad. They’re

brilliant but dull. They don’t have enough

imagination to see where their own work is leading.”

“Where might that be?”

“Beautiful psychosis, leaping from one mind to another.”

“But the software isn’t organic. If it’s implanted in your

brain, surely it can’t be contagious

and passed along like a virus,” I said.

“Only in an act of physical intimacy,” she replied,

“Not ‘sexually transmitted’ in the usual sense,

but by using the mental and emotional uniting of two individuals

to create a telepathic circuit as they are becoming one flesh.

It opens a channel, a conduit for emotional connection,

one of the ‘unintended consequences.’

Another is that the person possessing the powers

granted by the software becomes utterly irresistible.”

She already looked like god’s au pair to me.

“I think you had a head start.”

“Thank you. You believe your job is to find me and

bring me in?” she asked. I nodded. “But your real job is to

lead them to me.” She might be irresistible,

but I resisted the urge to look over my shoulder.

“OK. They want to collect you and divest you of the software.

Isn’t that what they did with your fellow test subjects?”

“All of those poor saps are dead,” she said. “With

the possible exception of the one at the CIA.

Unless they’re in a post-lobotomy vegetable bin,

serving as a sort of human salad bar.

The stories Heckle and Jeckle told you are true,

up to a point. What they didn’t mention is that they

hired five drifters without family or close friends,

including the ones in a coma and doing time,

to play the roles of the original fellows, now translated

into the past tense. They’re covering their asses.

They intend to put me down.” She sighed.

“Unless they plan on hooking a generator up to my

brain and using it to manipulate the stock

market and control political upheavals.”

I tried to catch the eye of a waiter, but he was busy

poking his cell. A busboy trudged by pushing a

a trolley of dirty dishes, but he was wearing a headset

and muttering into a little microphone.

If she was on the run from my clients,

and I had been sent to find her and bring her back,

what was she doing finding me? And how

had she smuggled herself into the

society of my sedan chair chauffeurs?

“I certainly didn’t imagine you,” I said, “so how did

you manage to infiltrate a phantasmagoric sorority?”

“There was nothing extraordinary about it, she explained,

“The Head Trips software and Limbic Limo app are interactive.”

“We weren’t really in Hawaii, were we?” I asked.

“I’m afraid not,” she said, “But my mother’s mother was born in the islands, and I’ve never been. I’d love to go there with you sometime.

You could help me pick out bathing suit bottoms for the trip.”

“But that means we’re not here either. So where are we?”

We had been sitting opposite one another

but now she got out and slid in beside me.

A single button held her suit jacket closed.

As she took a deep breath, I could feel

the threads straining for their lives,

taxed to the point of reckless endangerment.

She reached up and removed the jade pins

and her hair cascaded to her waist, a nocturnal

waterfall at midday. She re-crossed her legs,

cutting the ribbon to open a new dimension.

If the skirt rode any higher, I thought, I could

read the laundry instructions on her underwear.

Her breath smelled of rum and crushed maraschino cherries

and her tanned skin looked dusted

with hibiscus, carrying me back to Kauai.

Fiddling with the button, she said,

“Somewhere safe. For now.”

“Why did you want to talk?” She ignored my question.

“I call my breasts ‘The Other Moons of Jupiter,'”

she said. “Would you care to make their acquaintance?”

“Would you care to make their acquaintance?”

Finally, I had the advantage of her. She had no way

of knowing that I was already so in love

with a woman who had long ago ground

me under her heel that I could not lie with another.

I could admire Nadja, endlessly, could want to

want her, but I could never close the deal.

Now I sighed. Welcome to the world

of the well and truly hooked. Maybe it

would help me keep my head straight.

“I’m afraid I’m spoken for,” I said, feeling

hopelessly old-fashioned, even absurd.

“Well, there’s no need for, what’s the word,

consummation?” she said. “All it would take would be a

single kiss. You know, where I come from, they say that

the fate of the universe could hinge on a kiss, but

there’s no way of knowing which one it will be.”

Since I had nothing else to give her,

I reached into my satchel

and offered her the tangerine.

She peeled and ate it without taking her eyes off me,

slipping the individual sections into her mouth

and biting them delicately in half.

I couldn’t help wishing I were one of them.

“If we were to kiss,” she said, “it would be like

riding down a river on your back,

using your hands as tillers in the current,

out of your body, but fully inhabiting

your mind and mine at the same time.

The rapids would be the white braids of our blood

twisting together like liquid torchlight.

We’d be surfing on each other’s brainwaves.”

I didn’t suppose one kiss would blow my unrequited love cover.

I wouldn’t want the universe to come unhinged, after all.

She reached over, dug her nails into my neck

and pulled my mouth down to her own.

The kiss was all that she had promised, and more.

I felt harnessed to manta rays, pulled into the future

by my own roots, drawn to her origins.

And the strictures of time were suspended

as long as our mouths made a seal against the world.

I found myself moving from past to present to future,

as easily as treading tropical waters. Through the

rootlets of our kiss, I was able to escape into any

moment of my life, and to stay there as long as I desired

to, as it were, enjoy the view. I could return and

select another future when the choice was offered me.

But I realized that any alternate futures would

leave me elsewhere than this kiss, so why bother?

“Right now,” she explained,

after we had recovered our breath,

“they’re heroes of the techno-sphere,

but if word of this fiasco gets out,

they’ll become either felons or fugitives.

So they’ll never stop coming after me.

They have inexhaustible resources and all the exits covered.

But I have the software in me . . . and you, if you’ll help me.” I had already helped myself to her lips, I thought,

and gallantry has to count for something.

I couldn’t win back the love I had lost; it was gone for good.

I had been stumbling among my own

low-budget movies for a long time.

By now, even the better angels

of my nature were drunken bums.

But maybe by lending the lovely physicist

a hand, I could regain myself.

“We could consider the kiss a retainer,” I reckoned.

“Can you do that?” she said.

“Didn’t you already take their money?”

“After a fashion,” I replied. “I accepted their check.

But when I looked at it, all the zeros suggested

I was unsober and suffering from double, possibly

even quadruple vision. So I tucked it away until I

could take a second look. I haven’t cashed it yet.”

I drew it out of my inside coat pocket and studied

it again, the zeros turning into smoke rings

I might employ as vaporous leis and belly chains

for the women’s beach volleyball players.

While I deliberated, she slipped another

section of tangerine into her mouth.

I sent up a silent prayer of thanks to

my satchel and tore the check in two.

**

“So now that I’m, what’s the word, enabled?” I said. “How do I make the movies come on?

And how can I get some Raisinets?”

She entered into the complex business

of piling her hair back up and repositioning the jade pins.

“I’m afraid I made all that up,” she said,

“I just wanted you to kiss me. But if we get

out of this alive, we could go sit in a theater

balcony somewhere sometime and make out.”

“Right.” Maybe I would just forget about the Raisinets.

**

“But if we’re able to elude them, or remove them

from the equation, how do you plan

to get the software out of your head?”

“I don’t,” she said. “I’m sure that once

Heckle and Jeckle rid themselves of me,

they’d tweak Head Trips until it works the way

they intended. I’m the only living person who will

ever know what this first-generation rogue version is like,

what it allows you to see, to do, to know, to believe.”

“Such as?”

“As you’re aware,” she said, “I am a scientist.

So I’m familiar with physical laws.

But those laws only describe the mechanics of how things work.

For instance, the real reason for gravity

is to satisfy the longing of leaves.

Roots, I now realize, are mothers who never see their children.

Every pine needle on the planet

“is privy to the mind of the creator,

but aches to touch the earth instead.

Every star in the heavens hurts when we hurt.

You encounter a phrase like ‘icy interstellar winds’

and you think the universe a cold and hostile

place. But it’s not like that. It’s hard to be alive,

as hard for the inanimate as for the sentient.”

“And the software taught you that?”

“I think I’ve always known it. We all do.

The malfunctioning of the software taught me how to savor it,

to linger there, and learn the world anew. And although

I can’t prove it, I have a feeling that it’s an ability

my children will inherit. An important step in human evolution.

After a time, you learn how to navigate the joins

where your conscious and subconscious minds meet

and merge, where definitions dissolve and re-form.

These overlaps allow you to place your lips

on the beating hearts of other worlds.”

“Well, that sounds like fun,” I said,

just to hold up my end of the conversation.

“Yes, it’s like being poised on the border of a seizure,”

she said, “a convulsion that will either kill you

or allow you to live with twice the intensity.

It’s all accidental. Heckle and Jeckle had no idea

of what would happen when the software was

actually in place. That the dreaming and waking states

could be superimposed. Now I dream with my eyes open

and watch movies continuously when they are closed. Sometimes the movies unreel when

I’m in the midst of waking dreams.

Watching a movie while you’re awake and dreaming

is like playing multi-dimensional baseball.

Which base do you throw to when one could

be a newborn planet and another a dying star?”

“So you want to go back at them?” I asked.

“Yes, and take them off the board.”

“I won’t be a party to cold-blooded murder.”

“That’s not what I have in mind,” she said. “I have a better idea.”

I looked around and noticed that the WBVPs had

deposited us in Griffith Park, near the carousel.

I could almost feel the weight of my daughter

riding on my shoulders. The go-round music,

instead of the traditional calliope piping,

was the Stones doing “Wild Horses.”

My companion was wearing a sand-colored muslin caftan,

embroidered with seed pearls. For a moment,

the word undulant was the only one I could remember.

We were doing the beginner’s version of holding hands,

with only our little fingers linked.

“The fellows you call Heckle and Jeckle, they

mentioned that you’d recently endured a divorce.

And a minute ago, your said something

about your children’s genetic inheritance.

So there were kids involved? A custody battle?”

“Yes and no,” she said. “The reason for the separation

was my hope of having a baby. My husband objected.

But as it happens, I am with child.” She looked as

though she could be about fifteen minutes pregnant.

“Did you trick him into knocking you up? I asked.

“No.” She grinned rather wickedly. “I tricked him into

being out of town. I wouldn’t have wanted his seed in me.”

I couldn’t help wondering who owned the honor of being the father.

Of course, it was none of my business.

“You’re wondering who the co-author of my child is.” she said.

“It was one of my fellow test subjects.

A rascally and very clever young criminal fifteen years my junior.

He could have been, or done, anything. He only turned

to crime because he enjoyed outwitting the law.

Now he’s dead, which is as about as law-abiding as you can get.”

She sat in front of me on a magnificent, hand-carved

Arabian stallion, my arms encircling her waist.

I was breathing the scent of her hair.

All the places we’d been, Hawaii and Hollywood

and the aromas of this rolling park were in it,

even though we hadn’t really been there.

A triple-trick of memory, like touching a spring in a library

filled with false books and being admitted

into one whose books were true,

wherein a second spring led you into

a cavern and an underground spring, but no books.

There had never been any books, only the three springs.

A few riders ahead of us, I noticed a pair of young men

who were ignoring the screaming kids with their ice-cream cones,

preferring the sight of their respective iPad screens.

I thought I knew who they were.

I hadn’t troubled to wonder about the hikers on Kauai

or the waiter and busboy at the Hamburger Hamlet.

“Can Heckle and Jeckle enter into this fantasy of mine?”

I asked Nadja. “Yes, as the designers of the software,

and the ones who planted it in your head, they can come and go as they please. But they’re just hoping to overhear some scrap of

conversation that will tell them where we really are.”

Well, since I had no idea of our actual location,

they weren’t about to hear it from me.

“How did they get it into my head?”

“Through your phone.”

“My phone? I don’t even know how to use my phone.”

“Oh, but they do. Trust me. They can rewrite your past,

get you into the Sorbonne, score you Dodgers’ season tickets,

land your ass in the stony lonesome for life and even

make sure you have terrific wi-fi after you’re dead.”

Well, here was another mortar round lobbed into my vichyssoise.

Suddenly, my skull was turning into a switchboard

in a forties movie, operators frantically pulling

out plugs and jamming them back into other sockets,

patching into party lines, keeping the war effort going.

“Maybe I should change carriers.”

A gang of kids were jumping off their horses,

switching rides and scrambling around in front of us.

I lost sight of Heckle, unless it was Jeckle,

and feared he might have dismounted,

crouched, and worked his way forward

until he was in back of us. Nadja turned

her head and whispered to me, “Have you noticed

anything about the sites we’ve been visiting?

Anything autobiographical?” I gave it a moment’s

thought. “Yes,” I said. “They’ve been in chronological order.”

I met Kauai when I was twenty, then the Hamburger Hamlet,

then Griffith Park, where I used to play softball on LSD

with a confederacy of wild and trustworthy friends.

“We’ve been safe-housing in an actual location,”

she said, “and it’s the next stop on the fantasy tour.

So, can you guess where our flesh and blood bodies are now?”

I tried to plumb the depths of my subconscious,

which of course you cannot do consciously,

but a provocative possibility came to me.

“It could be a place where I used to go—”

She shushed me with a finger to my lips,

pointing behind us. Then she slipped off the Arabian

and darted forward through the other horses. I heard

a commotion behind me, and turned in time to see,

or sense, a crouching figure scuttling clockwise

away from us. Nadja returned a moment later,

grinning her wicked grin. “Let’s mosey,” she said.

Climbing off, I saw Heckle and Jeckle

glancing around as they meandered toward

the brow of a hill, doubtless looking for Nadja.

But a protective ring of my chauffeurs had encircled her,

doing one of those “Let’s go team!” cheers

where everyone throws their hands into the air at the end,

so the techno-merchant-kings walked on.

Then we were in the dark, heading east in a 1941

Ford Super Deluxe V8 woody in Washingtonia blue,

hugging the starletty curves of Topanga Canyon.

I was at the wheel. I couldn’t have Nadja dreaming and driving.

I wondered what had become of the

women’s beach volleyball players and

how I could send them Christmas cards.

The car was certainly my fantasy car,

and a joint in the Canyon the place I had been about to guess.

So how was I to distinguish between the Limbic Limo,

allowing me to cruise my own past, and the world of actuality?

Especially in Topanga, where nothing ever changes, thanks

to the ever-present threat of fires and mudslides

keeping developers at bay. I tried to see in the side-view

mirror whether I was twenty-one or, well, a generation or so older. The windows were open, the

midnight river of her hair

blowing back, her eyes shining with anticipation.

“What were you doing, back on the merry-go-round?”

I asked. “Counting coup on Heckle, unless it was Jeckle?”

“No,” she said. “I was employing a talent my baby’s father

taught me. He was a gifted second-story man, car thief,

con artist and forger, but he was also what in that world

is known as a ‘dip.’ In other words, a pickpocket. I lifted

the murderous little bastard’s phone.” “Wait,” I said, “Can you

do that? Take a device into a fantasy?” “That’s how it works,”

she explained. “Whatever you have on your person when the

app is activated stays with you. Your satchel, for instance.”

It was true. I remembered the weight of it on my shoulder,

even as we rode in circles on the Arabian.

“Of course,” she went on, “you can’t place a call from the fantasy. There’s no signal.”

She was dressed now in the height

of late sixties’ hippie-chick chic, faded Levi cutoffs,

a chiffon scarf converted into a halter top, and gloriously barefoot.

She dug into the pocket of the cutoffs and pulled out a phone.

I felt the one in my own jeans vibrate. “Hold on. Didn’t

you just say you couldn’t place a call from the Limbic Limo.”

“You can’t. We’re in Topanga Canyon, your old stomping grounds.”

“But this is my fantasy car.” “I know,” she said.

“I went out and found one, on the Santa Cruz Boardwalk.”

“But how could you know that?”

“I’ve been voyeuraging, as it were, through your fantasy life.”

“Wait a minute. You can see my fantasies,

even when you’re not in one with me?”

“Sure. Who knows? I might see myself in one someday.”

Pull in here.” We skidded into the parking lot of The Corral,

a dope, sex and cheap thrills hippie nightclub and bar.

Inside, I saw that it hadn’t changed at all either. The

bouncers still looked like oilfield roughnecks who had been

dosed with mescaline and mellowed about halfway out,

their hair long but greasy. The girls pirouetting on the dance floor

were out of Dante Gabriel Rossetti by way of the Grateful Dead.

But when I elbowed my way to the bar and learned that the

execrable white wine was still a dollar a glass,

I knew we must have flipped back into Limbic Limbo.

My head was going around faster than the Arabian.

The crowd parted for Nadja, who appeared at my side.

“So we’re back in the fantasy now, is that right?”

“Yes, the Corral burned to the ground years ago.”

“Are Heckle and Jeckle here, if here is the word I’m looking for?”

“Probably.” “So my dream date is with me, courtesy of the software,

and the boys are expected to slide in via their own side door.

They must be aware that we’ve put our heads together, as it were.”

“Doubtless,” she said, “but they have no way of knowing

whether I’ve turned you or you’re trying to take me back.

They can’t even tell if we’re together in the flesh,

only that I, as they, have invaded your fantasy.”

“Are they out there, in . . ..” I kept losing track of my tenses.

“Contemporary time?” “Not yet. But they will be.”

I scanned the crowd and the staff, and didn’t see

anyone who looked out of place. But on the bandstand,

among the traditional line-up of guitar, bass, drums and

piano, were two cats on bagpipes and a hurdy-gurdy.

Listening closely, I thought I could tell that the music issuing therefrom was prerecorded.

And, despite their efforts to simulate

funkiness, they couldn’t help giving off a kind of preppie vibe.

“So we are out there in the actual parking lot?”

“Well, no one has parked there for years.”

“Why did you take his phone?”

“Because his partner’s phone is able to locate his. And I

let Heckle (unless it was Jeckle) overhear just enough

as he crouched behind us on the merry-go-round to help

them pinpoint our location. So they should know

where we are, and be setting a trap for us right now.”

“And our advantage is that we know we’re walking into a trap?”

Instead of answering, she pulled me out the door, and I experienced

a feeling far beyond jet lag as I went from the territory of my

deepest subconscious to standing on the ground in the

same spot where I had just been in my head forty years earlier.

As we crossed the threshold, midnight turned to noon, and the

crowded lot became the blackened site of a disastrous fire,

the woody parked alone in the last of the morning fog

burning off like so many hippie girls

slipping out of your bedroom at dawn.

Nadja and I were in the front seat of the woody when

A black Lincoln Continental pulled slowly into the lot.

I knew it must belong to Heckle and Jeckle because

they had somehow managed to make it look nondescript.

When they climbed out, one was still in tennis shoes and

the other in hiking boots, but they might have swapped

footwear for all I could tell. Neither brandished weapons,

unless you counted their usual tablets, but they were all

the scarier for their lack of armaments.

Who needed firepower

when you could get so easily into the heads of your enemies?

They walked toward the woody, declining as always to make

eye contact, except with one another. Nadja had her ankles

casually crossed on the dashboard, her eyes closed. This might

have been her version of a drive-in. She could be watching McCabe & Mrs. Miller in her head right now. H (unless

it was J) walked to the driver’s side window and said to me,

“Congratulations. I think you’ve earned a considerable bonus.”

“I wouldn’t turn it down. Where are you taking her?”

“To a very comfortable treatment facility in Santa Barbara.”

He went around to the passenger side and bent his

head to the window. Only then did Nadja open her eyes.

“I’d like my phone back,” he said, almost smiling.

“Sorry,” she said. “I’m afraid I tossed it in the rubble,”

pointing to the remains of the night club. “Kind of petty of me.”

“Would you mind retrieving it?” he asked. “Not if you don’t

mind my using the . . . ladies’ room as long as I’m over there?”

she asked, gesturing to the battered port-a-potty that must

have been brought in for the clean-up crew in the wake of the fire.

She glanced at me, cutting her eyes to the scorched ground

by way of asking me to join her. “I’d better give her an escort,”

I said, “She might try to take a runner.” There wasn’t

really anywhere for her to go. Behind the toilet was a steep

hillside that would make for a suicidal tumble toward Ventura Boulevard.

Apart from that, her only exit strategy would have

been to hitchhike out. “Sure. You can stand guard.” We strolled

over, Nadja pretending to study the terrain. When we were about

where the bar would have been, she leaned over and picked up

a cell phone. With her back to H&J, and her bottom

in the skimpy cut-offs providing a distraction, she took a second

to push a few buttons on the phone, then stood and waved it at him.

When we got to the port-a-potty, she opened the creaking door,

and grabbed my wrist, pulling me in after her.

This could be even more awkward than trying to please

your squeeze in the lavatory of a commercial airliner,

I thought, misconstruing her intention. “Hurry,” she whispered.

“We only have a few seconds.” Instead of sitting, she tilted the toilet

to the side to reveal an ancient-looking trap door. She motioned

me down a ladder and followed, pulling the toilet into its original position to cover our escape, locking

it in place with a deadbolt.

“Where are we?” We had shuffled down a narrow passageway

into not quite a basement but more than a crawl space,

a small bunker or bomb shelter where we were

both obliged to crouch. Cinder block walls,

benches all around and sconces for lanterns.

“It’s an old hideout where my mother and her accomplices

waited for the Corral to close one night many years ago.

The trapdoor was just outside the rear wall and

this chamber is under the former site of the bar.”

When I gave her a look, she said,

“You’re not the only sojourner through your

own past in these parts. I was here in my infancy.”

“But the ‘ladies room’ wouldn’t have been here then.”

“It wasn’t,” she confessed. “I did a little reconnoitering and

reconnaissance here recently and moved it a few feet.

I also customized the john and the floor to accommodate

the lock. Now Heckle and Jeckle will be obliged to think we

either vanished or flushed ourselves into the Pacific.

More importantly, they’ll be forced

to use the Limbic Limo to look for us.”

I glanced up at the underside of the trap door,

only to realize that we were back in the nightclub,

and had the place to ourselves.

The lights had been doused, the stools were upside down on

the bar and you could still smell the sweat from the dancers.

It was shortly after closing. Then we were cowering in the

dark in a late model Oldsmobile. I had no idea of what was

was going on, but I knew it was no fantasy of mine. I could

almost hear Nadja’s heartbeat over my own. Then we were

back in the Corral but no longer alone. Heckle and Jeckle,

looking puzzled, were tilting their heads up and down and

turning them from side to side just like people who smell smoke.

I knew because I could smell it myself,

could see newly inspired flames beginning to curl up around

the bar, could feel bottles of hard liquor about to explode.

A jump cut later we were in the Oldsmobile again,

My eyes were Nadja’s eyes, opening wide with terror and exhilaration.

My fingers found the dampness where her bladder

had emptied on the seat and then we were back in the woody,

out of the fantasy, holding to the planet we are pleased to call home.

I wondered if I had ever met her mother.

“What was the story with your mom and her band of outlaws?”

“They arranged with the owners to torch the joint

for an even split of the insurance payout.”

“Were they radicals?” I asked. “SLA? Weathermen?”

“No,” she sighed. “They were junkies. Canyon rats. What began

as blissful truth-seeking on psychedelics had declined into

the hard truth of coke, speed and smack. It was a score.

Nothing more.” I remembered it all too well. I had lived here

during those years, in this green and golden fracture in the earth, the low laughter of water running alongside the road

like thoughts of old sweethearts half-forgotten.

There came a day when I couldn’t help noticing

that formerly euphoric friends were

turning into wasted specters with rotting teeth.

This was my first time back.

“I was about two and a half when they went up into the empty club

and my mom carried me out to her car, an Oldsmobile.”

“I believe I know the one.”

“I soon grew lonely, and scared. So I climbed out of the car

and toddled up to the door of the Corral in my giraffe jammies.

I had just stepped onto the dance floor when my mother

raced up, grabbed me from behind and ran out toward

her friends just as the first lick of flame began doing its work.

Ordinarily, I can’t remember the scene. But it comes to me

sometimes in dreams which translate into a fantasy I can

visit with the Limbic Limo. I guess you were allowed

to accompany me because we had kissed.”

No wonder, she was a very good kisser.

**

“Let me see if I have this straight. At first, Heckle and Jeckle

were controlling the Limbic Limo when they summoned me

to their headquarters, and then you took over after I set out to

find you. The fantasies were mine, but you decided when we

would move in and out of the Limo, right?”

“Yes, sorry for the confusion.”

“So what happened to them? Where are they?”

“Their bodies are in the Lincoln, though they’re no

livelier than your average rutabaga.

What’s become of their minds is a little harder to explain.” I waited.

“Well, they, their minds, are trapped in the last fantasy

they stowed away in, mine.”

“But they’re alive?”

“Oh, sure. I told you I wouldn’t involve you in a homicide.

But they’re in the same vegetative state they were planning

to leave me in when they dropped me off at the treatment center.

Only I would never have come out of it.”

“Will you release them?”

“Yes, as soon as I’ve put a continent or two between us,

and gathered enough evidence to prosecute them

for manslaughter and various other misadventures.”

“How did you do it?”

“This is going to sound preposterous, but there are occasions,

mere instants, really, when Head Trips, the Limbic Limo

app and the dreaming process, fuse in my head.

As I became more familiar with the software,

I realized I could, at these instants—at least I believed I could—

orchestrate psychic events, traumas, if you will,

in the subconscious of other individuals who were

using the same software to trespass in the same

psychic domain where I had taken up temporary residence,

a total mind-fuck, if you like. But it was all theoretical

until the moment when I bent over to pick up Heckle’s phone,

unless it was Jeckle’s. I deleted the app from his head,

so they’d have no way to get out. They’re stuck for the duration, at the edge of my mother’s arson,

unable to travel anywhere but on the path between her car and the fire.

I considered stranding one in your Topanga

Canyon flashback/fantasy and the other in mine,

but I decided you were entitled to your privacy

and deleted it from your head too.”

A few miles before we struck the Coast Highway

I pulled off, got out and threw my phone into Topanga Creek.

**

We dawdled north along the coast, the two in the back

looking like they were napping. She had called the facility

from the stolen phone and changed the reservation from one comatose woman

to a pair of comatose men. Since

the call was from the same number that made the

original arrangements, it aroused no suspicions.

“Those men killed your lover, the father of your child.

Won’t you be tempted, since you have them at

your mercy, to subtract them from existence?”

“Tempted, perhaps. But I will stay my hand,

if only because I’d like to look good in your eyes.”

Her smile had two futures in it and I felt paid in full.

**

God knows she looked good in my eyes now.

She had discarded her hippie-chick rags

in favor of a pleated white ice-skating skirt

and a cashmere sweater in forest green

that fit her as though fashioned of moss.

She’d changed in the car as I struggled

to keep my eyes on the road, a discipline

for which I will never forgive myself.

We had dropped off our cargo and she had handed me the key

to the woody in Pismo Beach, saying I should think of it

as the bonus I hadn’t received from Heckle and Jeckle.

It was time for goodbyes.

“I believe I can eventually control these powers,” she said,

“using my own mind as the steering mechanism.

One day, I will be able to extend my sympathies

into the heart of all matter. And my child

will be born knowing all that I have learned,

and soon will outdistance me. One day, we’ll be able

to enter one another’s dreams, effortlessly and at will.”

“Do you know the baby’s gender?”

“No. I want to be surprised.”

She was rather old-fashioned herself.

“Have you decided on names?”

“D’Artagnan if it’s a boy. Tatiana if it’s a girl.”

“How will I get in touch with you, should the need arise?”

My voice faltered and failed me.

“If you have a writing implement,” she said,

“I’ll give you my contact info.”

I reached into my satchel and drew out the fountain pen.

She took it from me, uncapped it, unfolded my fingers,

and wrote five minuscule letters in Cyrillic on my palm.

I reached in again and brought out the magnifying glass.

Now I could focus but I still didn’t understand the word.

“It means ‘Nadja,'” she said, “and it will never wear off.

If you want to see me, stare at your open hand for ten seconds,

then close it hard and think about me with all your might.

I will make my way to you.” Was she teasing me?

I must have looked dubious, because she kissed

me primly on the lips and said, “A minor super-power,

granted by the software. Call me.”

**

I never have, though I would like to meet her child,

and learn what kind of movies D’Artagnan or Tatiana likes.

Whenever I watch a movie now, with my eyes open,

I wonder if she is watching the same one, at the same time,

with her eyes closed, a funny kind of movie date,

Raisinets or not. There was so much I should have asked her.

For instance, if we were in my fantasy during our ride on

the Arabian, why wasn’t she wearing spurs instead of sandals?

I guess it was because she had a private entrance.

For a time, my libido was not entirely my own.

When people ask about the meaning of the strange

markings on my palm, sometimes I allow as how

they are in a long-forgotten language and refer to

The Other Moons of Jupiter. And sometimes I just

say they mean “Head Trips,” and let it go at that.

Such is the life of a private eye.

Next week: Part 3

Michael Larrain is the author of 20 books of poetry, prose fiction and children’s storybooks. He was born in Hollywood, California in 1947 and currently makes his home in Sonoma County. His writing has appeared often here at The Fictional Café.