Seventeen-year-old Iza auditioned on a whim and got accepted (on a scholarship) to a creative arts prep school. Even with just a year left until she graduates, attending this school will give her the edge she needs to be a successful classical violinist and give her more options than what she currently has in the impoverished town where she grew up; but without the support of her mother getting there will be a challenge. After convincing her best friend to drive her to school, working extra shifts to save up money and having her granny forge her father’s signature on the application, Iza is finally ready to make the great escape to Everleigh. 1 She has pluck, they say, with optimism in spades, surely all her dreams will come true. “Iza Jones, are you scared?” Tiara quipped. I’m always nervous until I step out on to the stage, until I place the bow to violin, then the calm washes over me; a balm on those tight nerves. “Why couldn’t Renee drive you?” “Wouldn’t,” I correct. Rene was my mother; Who’d forbid me from auditioning. Tiara laughed, a trinket of a sound giving away how insincere she was. Tiara was that one friend: who grew up on your street, who played with you out of convenience, who you knew was an asshole but they were your asshole loyal till the end, dependable as fuck, and despite it all, you’d grown to love them, that was Tiara. We had things in common too, smutty books, being half-white without actually being white, jamocha shakes, celebrity crushes, and big dreams; but that’s where our similarities frayed and opposites began. Tiara was prep where I was inner city, I was kind when Tiara was sharp-tongued, Tiara was bored when I felt intrigued, and her white family rejoiced when mine had denounced. I didn’t feel any kind of way about it; these things were what they were, and despite it all, there’s always hope, this audition was tangible hope; a reminder of who I am —an indisputable fact— and I’m claiming what’s been ordained mine. No one could stop me, not even my mother, I wouldn’t allow it. 2 I grew up in the inner city, a midwest diamond in the rough that reverted back to coal once the automotive industry pulled out to pull in somewhere else; factory rats left scurrying to jobs that soon wouldn’t exist; my mom was one of those rats, always teetering on about how she should have relocated (to Hawaii) when they’d offered. Lucky for us, mom bought our beautiful craftsman before our financial instability took root, securing the perfect mask for how poor we were and how bad things would get; No one looks too closely at pretty things, they’re accepted as is. On the same block at the opposite end from my house lived Tiara. Her father was one of those inferior superior jerks who was less educated than he believed and only became bearable when he (or his company) was buzzed; my mother —cut from a similar cloth— thought he was great and Tiara’s mother must have too, because she flitted around him like a moth to a flame; enamored, but slowly burning up. Tiara’s mom was kind, with an empathetic generous spirit; she cooked for me when I visited, patting my cheek while calling me pretty, always gushing about what a good influence I was, what a good friend I was, and I ate it all alongside the delicious pancit she’d cook, beaming like a little sun because I never received praise like that. It’s a powerful thing to be good enough. So while, our moms bonded over spilled tea and hot coffee, sipping as they endearingly jabbered, Tiara and I bonded too; it was just that simple. 3 My father was a free spirit turned jaded by circumstances sprung from trauma. What I mean is, systematic racism and oppression shaped his parents, and his parents’ parents, backwards on and on, unto the very beginning when our ancestors first stepped foot on this soil. It’s not an excuse, it’s a reason, sometimes parents are the way they are ‘cause their parents were the way they were. That’s the generational curse: being unable to become something new, perpetually stuck being what our parents, intentionally or not, made us become. We’re like them because we are them. The good news is, being alike doesn’t mean identical, and sheer will can break the curse. My grandmother did the best she could for my father; I hate clichés, but this time it’s true. Granny was barely my age when she fell in love, got married, fell out of love, became a barber, flew north from Texas to Michigan and worked—eventually opening up the Ninth Cat. You see, she was the ninth child born and the barbershop her last life; it’s not an excuse, it’s a reason. I think of the child version of my father often. It makes my heart so full of sadness. If only the curse had been broken sooner, what a man he could have grown into. I’m young of course, not quite eighteen, and people will say I don’t understand the intricacies, of adult problems, but I know doing the right thing is ageless, being strong isn’t tied to brawn, and wisdom is afforded to all who seek it. My fate will be different, —I’m sure of it— music is my ticket out, my magic to finally break the curse.

***

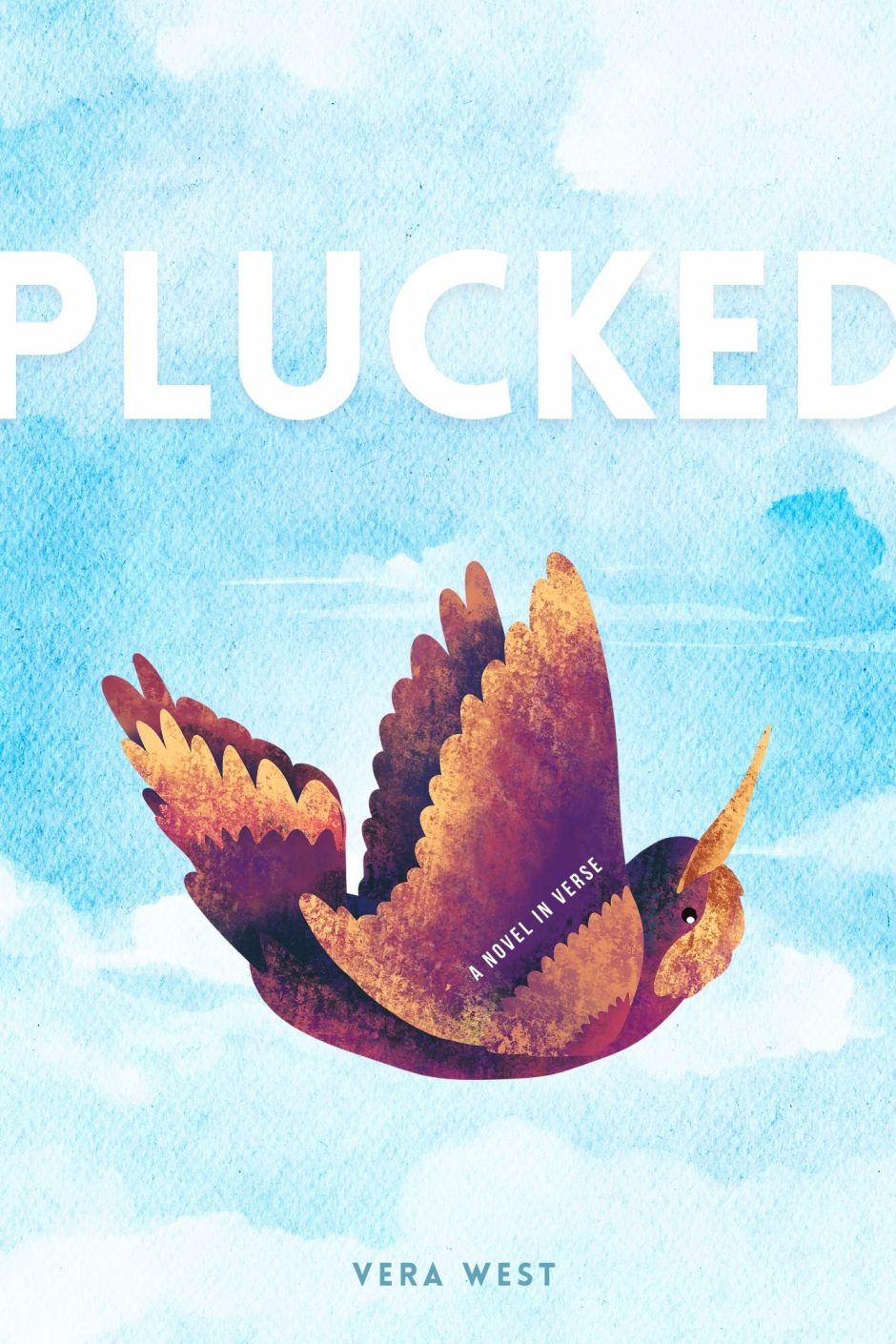

After a messy divorce from music, West fell into a torrid love affair with writing. They’ve been somewhat happily married since 2013 when her first novel was published in partnership with Schuler’s Books & Music Chapbook Press. West graduated from Grand Valley State University with a Bachelor’s of Art in Writing in 2011 with an emphasis on fiction and poetry. Since then, West has self-published a handful of novels and three collections of poems that tackle themes of love, redemption, cultural identity, social issues, and the afterlife. West resides in Michigan with her family and can often be found reheating the tea she forgot she made or reading a good book.