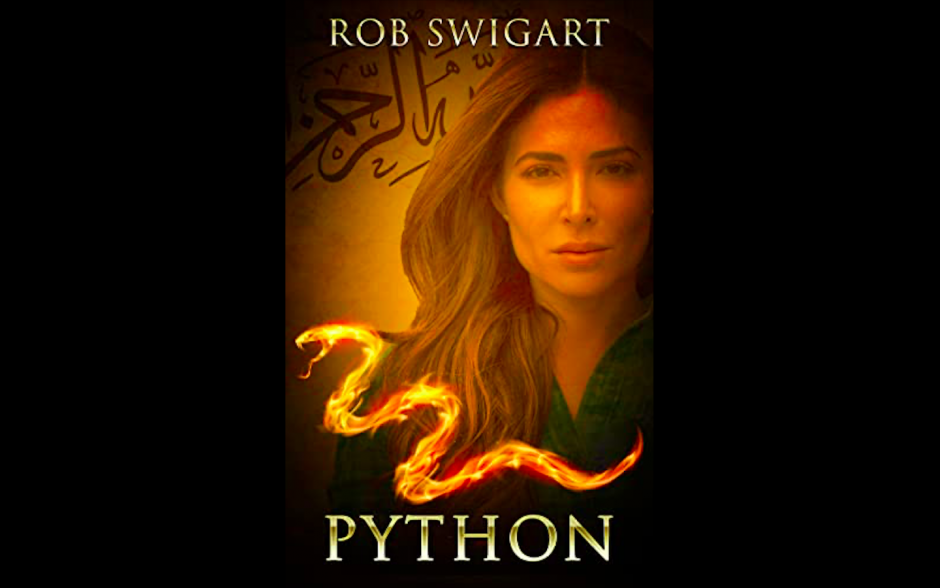

Rob Swigart brings Lisa Emmer back for Python, Book Three of his fascinating mystery series.

I met Rob Swigart on the afternoon of April 29, 1977, at the University of Oregon Bookstore, where he was autographing copies of his first novel, Little America. Although we lost touch with one another for many years, Rob published more novels, many of which I’ve read. One day, perusing my bookshelf, I picked up Little America again and read Rob’s inscription. I turned to my computer and quickly found an email address for him! I’m very happy to know Rob once again, today as a friend and fellow novelist. Rob shared “Water,” a short story with us on FC a few years ago, and today we’re helping bring attention to his latest work, Python, the third book in his series about Lisa Emmer—of whom there will be, at least, a fourth.

The Lisa Emmer books are all published by booksBnimble in Kindle editions. They are, in order:

The Delphi Agenda: Papyrologist Lisa Emmer’s world flips when the Surete meets her at a Paris Metro station with news of the savage murder of the esteemed historian Dr. Raimond Foix, her friend and mentor in the study of ancient documents. Horrified, Lisa finds clues at the crime scene left behind for her by her mentor—clues to a secret kept hidden for centuries. But these clues make her a prime suspect in the murder investigation, and also put her directly in the crosshairs of a deadly commando group that proves to be none other than a contemporary offshoot of the Inquisition.

![The Delphi Agenda: Lisa Emmer Historical Thriller #1 (The Lisa Emmer Series) by [Rob Swigart]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51CRmJ3r5BL.jpg)

Tablet of Destinies: A clay tablet turns up containing a prophecy of demons, a snake goddess, and the birth of a miraculous but possibly disruptive child. It is a prophecy so dangerous the tablet was smashed to bits, the shards scattered to every city in the ancient world to prevent reassembling, until a Jesuit scholar’s vision sets the prophecy in motion in Paris, where the pieces have lain for centuries. But half a world and three millennia away from the source, yet very close to her current home, Lisa Emmer has been chosen the Pythia, head of the Delphi Agenda. Because of her gift of sight and training in ancient world studies, it falls to Lisa to help solve the 3,000 year-old mystery.

![Tablet of Destinies: Lisa Emmer Historical Thriller #2 (The Lisa Emmer Series) by [Rob Swigart]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51s8Uj1uNAL.jpg)

Python: To his million young video followers, six-year-old Felix is their beloved science teacher. To the little-known-of Delphi Agenda, working, as always, for peace and harmony, he’s not only a prodigy; he’s a prophet with the potential to become even more powerful than Lisa Emmer, the current Delphic Oracle. Felix may even have the power to save the world from humanity’s dumpster fire. Yet to those few who understand the enormity of his powers, he’s a pawn they could put to their own use. So everyone wants a piece of him, and kidnapping is not off the table. In fact, it’s pretty likely. Felix and Lisa, his mentor, can see that coming a mile away.

![Python: A Lisa Emmer Historical Thriller (The Lisa Emmer Series Book 3) by [Rob Swigart]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41yz0bnw0rL.jpg)

Rob doesn’t insist you reading his Lisa Emmer series in order, and so herewith has provided the first chapter of Python with which to intrigue you.

Python is on sale on Amazon/Kindle at $2.99—discounted 25%. If you haven’t read the first two, the author recommends it and so do I. You can pick up The Delphi Agenda and Tablet of Destinies on Amazon/Kindle as a twofer, here.

I’m looking forward to the third volume of Rob Swigart’s Lisa Emmer series, and I hope you are as well!

All the best in 2022,

Jack B. Rochester, your Editor-in-Chief

Chapter 1

Candlemas: Channel Three

The boy on the video spoke English without a definable accent. “This is a pine wilt nematode,” he was saying in a high, clear voice, gesturing at a photograph on the left of the screen.

“Who is this?” David Re demanded, gesturing at the screen. His large hand was barely visible in the gloom.

The photo looked like little more than a loop of thread. The boy continued, “You can see the pine wilt nematode’s not much to look at. This picture was made a lot bigger with a microscope. The worm is actually skinnier than a piece of thread. Now, Pinewilt may be teeny-tiny, but kids have sharp eyes and see things grown-ups miss. So tell Pinewilt’s story to all the grown-ups you know, the ones who can’t see well. You’ll amaze them, and they might learn something, because today everything is changing, and everyone needs to know about. . . .”

The man next to Re muted the sound.

They were seated on a couch in a conference room with violet light strips outlining the ceiling. The one with the remote was Chrétien Labrunie. “He’s just a kid, Dr. Re, but he has nearly a million followers. He teaches science to other kids, for God’s sake, and they lap it up. Hard to believe from the way he talks that he’s only six.”

“Six? Really? So he’s a prodigy.”

“Yeah, a smart little bastard all right. I think he may have what you’re looking for.”

The clink when Re set his empty glass carefully on the coffee table sounded very loud in the silence. “And what would that be?” he asked, leaning back and clasping his hands behind his thick neck. They both knew the answer.

“The future,” Labrunie replied firmly.

David dropped his hands in feigned surprise. “Eh? May have what we want? So you’re not sure?”

“He makes predictions sometimes, small ones, but real. What he says comes to be.”

Re scoffed, “There are techniques to make answers to questions about the future seem pretty accurate. Don’t confuse research or misdirection with the supernatural, Chrétien.”

“Certainly not.” Labrunie paused the video.

“Mmm.” Re mulled his thoughts like Christmas wine, then changed the subject. “How long have you worked for us, for Python?”

“Five years, more or less.”

“And we got you installed in the Vatican, correct? As a cardinal.”

“Yes, of course.” Labrunie was subdued now; he knew what was coming. The boy’s face on the far wall remained frozen mid-word.

“And in that time, have you found us any prospects for Python, for the Omphalos project?”

“None certain yet. The Curia moves slowly, but I have a new contact in the Congregation for the Causes of Saints with some very promising leads. As you know, it takes years to investigate and prove a potential saint had the gift of prophecy, and while there are dozens under investigation now, most won’t pan out. Don’t worry, I’m keeping tabs . . .”

“Well, there, you see it,” Re interrupted. “You don’t have any. I remember you came highly recommended by your previous employer. A particularly imaginative covert operative. Isn’t that right?”

“Yes, that’s right.” Chrétien proffered this agreement with caution.

“Imagination is why you suggested we arrange for your minor orders and then for the Holy Father to promote you to cardinal, which was not inexpensive. We did this because you promised as a cardinal you could move things along. A cardinal, you said, would have access, influence, power. When we hired you, Omphalos was just beginning. We had acquired some helpful DNA on our own. We now need real subjects. Our goal may be a long shot, yes, but the Vatican is by far the most target-rich environment.” He stood and paced slowly around the room, hands in his pockets. He seemed to be growling, very low in his throat.

Abandoned on the couch, Labrunie had to look up. “Yes, it is.”

“You were to find us individuals with a certifiable gift. A saint, if you will. This may seem a fool’s errand to some, but the goal emerged from our rapidly evolving genetic research, correct?”

“Correct.”

Re turned back to the vague shape hunched forward on the couch. “Now, I can’t see how we can do more to help you, unless of course you would like us to get you elected Pope?” The sarcasm cut like acid.

“No, no,” Chrétien held up a hand to ward off this assault. “That wouldn’t be necessary. In fact that would hinder my freedom.” He realized he was growing defensive and closed his mouth.

Re paused in front of the screen. “Yet now you bring me this video of a child prating on about worms?”

“Bear with me. This boy is unique.”

“Oh? So he’s a saint with the gift of prophecy, then? Because a saint with the gift of prophecy would be our target subject.”

“Of course not, he . . .” Chrétien caught his mistake and changed direction. “He once predicted a flash sale of microscopes at a small educational store in Neuilly-sur-Seine. A week in advance. I looked into it. The store had no sale planned, only decided at the last minute to shed excess inventory. But a group of parents was waiting when the store opened. They heard there was going to be a sale and bought his entire inventory. The patron hadn’t even made a sign. He had never heard of Channel Three. But yes, he said, of course, come in. Now he watches Channel Three and tells his customers about it. Science for kids taught by a kid. A miracle, he called it.”

“A miracle.” Re’s voice was flat. His close-cropped gray hair was haloed by light from the image of the boy looming behind him.

“Yes.” Labrunie covered his confusion by going to the mahogany table against the interior wall and refilling his drink. He held up the bottle, otherworldly in the faint violet light from the ceiling corners. “Refill?”

“No.”

Over the years Chrétien Labrunie had learned David Re could be irritable and unpredictable, but he hadn’t expected trouble with this find just because it wasn’t from the Vatican. Times like this he wished he could deal with Re’s brother Dario, but he seldom saw him. With a barely audible grunt he put the bottle down and half-emptied his glass. False courage, he knew, but it warmed him.

“It’s the pandemic,” he blurted.

Re cocked his head but remained silent.

“Like everyone, he’s been trapped inside. Now it’s almost over, he’ll be going out. Then we might be able to gain access to him, you see?”

Re wandered back to the couch. Instead of answering, he said, still in the sarcasm lane, “So this kid has so many followers because he gives shopping advice?”

Chrétien deflected it. “He’s the best and most immediate prospect. He’s young. I trust the source.”

“Source?”

“A former seminarian well connected to science education named Fabrice Mirabeau.”

“Like the bridge?”

“Yes, like the Pont Mirabeau.” He sat down again next to the much larger man. “Trust me, Dr. Re, this is your best prospect. I know he’s not Catholic, at least not practicing, and he’s young, but Fabrice knows what he’s talking about. The kid has talent.”

Re snorted. “All right, we can discuss him. So tell me, this isn’t YouTube, so what are channels one and two?”

Chrétien relaxed into a sigh of relief. “There are no others. Channel Three is a stand-alone site driven by word of mouth. Or word of little mouths, heh.”

“Why Channel Three?”

“Channel Three’s motto is, ‘We don’t pretend to be number one.’ It’s either a joke or false modesty, maybe. No sponsors, self-funded.”

“By a six-year-old?”

Labrunie shrugged. “Why not? It’s cheap to set up a video web site.”

“OK.”

The cardinal added hopefully, “Also, they live in Paris.”

“That’s convenient,” Re observed with a bit of snide in his voice. “All right, let’s see a little more.”

The boy’s white shirt and red bow tie suggested a genuine remote science teacher with neatly combed straight dark hair and dark liquid eyes. Highlights helped animate his presentation.

Labrunie pressed the remote and the image came back to life. “Pinewilt munches away happily until the host pine tree wilts and dies, then he moves to a new tree. How does this tiny worm kill a tree? How does it move to another tree? It can’t fly and it’s too far to crawl, or worm, its way. Well, it gets a ride in the breathing holes of a pine sawyer beetle, which eats sick or dying pine trees from the inside. The trees are sick thanks to Pinewilt, and Pinewilt moves around with the help of the beetle.”

A spotted beetle with long inward-curling antennae like a handlebar mustache replaced the worm.

“See, the beetle depends on Pinewilt, so he says thanks, Pinewilt, carrying you to another tree also helps me.”

He grinned broadly at the camera.

“Here’s the fun part. Pinewilt can only catch his ride at the very exact moment the beetle turns into an adult to start munching his way through the bark back to the surface. If he gets his timing right, they fly off together to the next picnic. Pinewilt waits patiently while the sawyer beetle eats a hole into the new tree before getting off. The beetle’s sort of a flying bus.”

A pine tree dropping brown needles replaced the beetle.

“My question is, how does Pinewilt know what time it is without a watch or a calendar? Interesting question, right? He’s a worm you can’t see without a microscope. He’s got no brain, no nerves, yet knows and acts in perfect timing with a completely different creature! They help each other. He climbs on and off at the right time, and the beetle doesn’t mind. The thing is, the beetles have what is called non-synchronized emergence, which means they’re like people, and don’t all change into adults at the same time.” He shook his head, grinning. “It’s magic, like Harry Potter, but that’s how nature works. Is it just chemistry and physics? How does Pinewilt know a beetle is about to change? How does this tiny worm decide when and how to act without a single nerve cell? And that’s just the beginning of the story, because the pine trees have a role to play, and bacteria in the gut of the worm, and the mushrooms around the pine tree’s roots, and so on.”

The boy was shaking his head in wonder. Re growled, “All right, that’s enough.”

The image froze again with a friendly smile. Grudgingly, Re could see his appeal: to a kid, he had a face you could trust.

But a child? Re preferred the saints they had, with certified, proven records, even if their samples weren’t the best.

A wall slowly became transparent and for a moment the boy’s face appeared reflected in the glass. The lights came up, the face faded away, and a deep blue winter sky dancing with particles of ice amid tall glass buildings remained. There was a slight chance of snow later, but Re thought it unlikely. Paris hadn’t seen snow in years.

Chrétien got up to pour himself another drink. “So, what do you think?”

“Mmm.” Re gnawed on a knuckle, looking out. He turned. “I don’t care for it, but all right, who is he?”

“Félix Emmer, born in Spain to a Spanish mother. Brought to Paris as an infant by Lisa Emmer, an American resident of Paris who adopted the mother. They all live in the same building on the Rue du Dragon.”

“Mmm. I’m not entirely convinced, but he might be interesting. Predicting a flash sale could be a lucky guess or the owner decided on the spot when parents showed up demanding microscopes. Maybe the kid created the future by making this prediction.”

“There are others . . .”

“Fine, we’ll look at them. If real, this could be helpful. Question is, how do we prove his gift? There’s no point wasting time if we can’t prove he has it. The Vatican’s methods are time proven and effective. They would do the work for us.”

“But so slow, Dr. Re. We would need a test to make sure. I don’t know.”

“Don’t ever tell me you don’t know!” Re snapped. “Never. Are you working against us? Who’s paying you?”

“No, no, not at all. What if we create an event in advance, something random that would trigger a prophecy specifically by the boy?”

“Pah. Saints and cranks often predict the end of the world. No one pays attention, so if it came true it would be quite useless now, wouldn’t it? So far, thankfully, they’ve all been wrong. Listen, it’s already February. Omphalos launches right after Easter. Whatever we do to determine if this boy really has the gift of prophecy, it will have to happen soon. Prove it, and we’ll need a way to acquire samples. As you know, this gift is rare, despite the hundreds of saints supposed to have had it. I imagine it’s like UFOs, most sightings are easy to explain, but a few remain a mystery. So not as rare as a genetic disease that has only one diagnosed case in the world, but certainly less common than green eyes. It’s a gift, not something you just pick up off the street.”

“What if we create a disaster of some kind? We can’t really conjure up a storm or volcano in Paris. Nor can we flood the Seine, but . . .”

“No,” Re agreed. “Can’t threaten some random individual, either. No one would pay attention to an announcement that a bus was going to kill a homeless person. Happens all the time and wouldn’t be taken seriously, even after the fact.”

“So, the President? Pop star? Mass terror?”

“Normal targets, too common. Any warning of terrorists or prominent targets would sometimes end up being true. To be effective, we would have to know in advance, in which case it wouldn’t be a prophecy.”

Labrunie tugged on his lower lip, hiding the panic that his mind was empty of ideas. Where was his vaunted imagination when he needed it?

“Besides,” Re continued, “finding a willing terrorist or potential murderer could prove difficult. Half the time such people post their plans on social media and make a mess of it. This operation requires trust.”

Labrunie threw up his hands. “All right, what do we do?”

Re went to the vast window and looked down on the street far below. The figures were so tiny, barely moving, each a human. The little cars going to and fro.

Re thought out loud, his back to Labrunie. “We’d have to threaten the boy directly with something imminent, not leave too much time between inevitability of the threat and delivery. Avoid giving his family time to think it over. It would be best if we can include the mother and this Emmer woman. They might not notice if we did something minor or couldn’t deliver it. Lives must be at stake; the more lives, the better. If they don’t foresee it and die, well, collateral damage is inevitable. To make it stick we’d have to trap them somewhere. To survive they would have to know it was coming.”

Chrétien was skeptical. “How would we do all that?”

“Let me think.”

Traffic was jammed up at the intersection to the left just before the esplanade of La Défense. This was exactly the kind of place terrorists threatened with a bomb in the movies. Vast, crowded spaces like stadiums, train stations, high rise buildings, department stores . . .

Department stores.

“La Samaritaine,” Re said softly.

“Eh? What about it?”

“One of the most iconic buildings in Paris, recently renovated. The stores are open, the offices occupied. But there is still some major infrastructure work out of the public eye. A Python construction subsidiary has a contract with access to the sub-basements.” Re smiled, and though he was built like a bull, the smile belonged to a wolf. “You get an office in the building and lure them to it.”

“Lure how?”

“Jesus, Chrétien, I don’t know,” Re said dismissively. “That’s your job, you’re the one with the covert imagination. Figure it out.”

Labrunie was warmed by Re’s confidence, but a concern his plan might lead to something unpleasant still nagged at him. Re, he thought for the hundredth time, was… erratic, unsettling. “All right,” he said at last, tone subdued. “Then what?”

“And then!” Re almost bounced with delight, like a sadistic child about to pull wings off a butterfly. “Then the building comes down. It’s a trap, Chrétien, that’s all. Division of labor: I’ll take care of the trap. If the boy is to survive, he will have to know in advance what will happen and take appropriate action. The bait is your job, Chrétien. It’s what we pay you for. Do it right, spring the trap, and it should pay off well for you.”

“Yeah,” Labrunie said softly. “It should.”

***

Rob Swigart has worked as a technology journalist and technical writer, scripted computer games such as the famous Portal novel that became a game, written for television, published many novels (Little America, The Time Trip and the “Thriller in Paradise” trilogy) and a hundred or so poems. Rob did story, scenario and report writing for the Institute for the Future in Palo Alto, CA, and was for several years a Visiting Scholar at the Stanford Archaeology Center (during which time he published two archaeology textbook-novels). Besides his Lisa Emmer trilogy, his most recent novel has been Mixed Harvest: Stories from the Human Past, narratives of daily life in the deep past and those who lived through millennia of exploration, hardship, and uncertainty, during the evolution of farming to the arrival of modern humans in Europe. Of his own life he remarks, “It’s generally been a very good time.”