“Water? What do I think about water? I’ll tell you what I think about water.”

Lyman was angry.

The silence went on.

“Well?” Alford prompted. “What do you think about water?” He tried to keep his question flat, so as not to acknowledge Lyman’s fit of pique.

“I try not to,” Lyman said, at last, deflated. He put his head back and closed his eyes.

Alford did not see how this was possible. Lyman sat in it. Or rather, he lay in it. Was lying. He was lying too. Alford knew that as well.

Lyman did not try not to think about water. To try to not think about water would have meant humming meaningless jingles or reciting nursery rhymes or doing advanced algebra in his head or most likely doing nothing but think about not thinking about water, which Lyman, for one, was unprepared to do since he was lying in a large body of the stuff, a bathtub to be specific. Was surrounded and to some extent supported by it. Was made up of it to the extent of some sixty-five percent. Drank it when thirsty. Was carried to term in a sack of the stuff, along with some salts and other substances. (Babies, by the way, Lyman almost said aloud, are made up of a higher percentage of water than adults. He did not know why this should be.)

Lyman was watching crimson ribbons unravel from his wrists into the water, which was hot. It was wonderful, he did think then, how water maintained its transparency. Even when it was a gas or a vapor, it allowed sunlight to come through in just the necessary frequencies for human vision. And it was a gas, or vapor, well within the normal temperature range for life on Earth. A wonder.

The crimson ribbons were blood, of course. Lyman was probably a Roman Senator today, disgraced and dying of a surfeit of good taste. Falling on one’s sword was messy, not to mention the scarcity of swords, hard to come by in this day and age.

Water also contracted when it cooled. Then, as the temperature fell towards zero degrees centigrade, it expanded again, which accounted for the extraordinary phenomenon of ice, the solid of water, actually floating. Which meant that fish could live safely through the winter beneath the frozen surface.

Nothing else did that. No, it was very difficult not to think about water. The crimson ribbons were only crimson because they contained rusty iron atoms in the hemoglobin. Mostly though, his blood was water, too. Eighty-three percent.

He stirred himself. “I’ll tell you what I think, Alford.”

“What do you think, Lyman?” Alford was now seated on the lid of the toilet, watching Lyman bleed to death in the tub. Steam, or condensed water vapor, hovered over the bath. Water was very good at holding heat, which is why it was so important for regulating the planet’s weather.

Lyman seemed less angry now. A certain fatigue was entering his voice, perhaps because he was leaking blood. “I think,” Lyman sighed. “Because I am.”

“I’m not sure that’s quite right, Lyman.”

“Perhaps not, Alford. I won’t debate the point. I will only say that if I am not, it is not likely that I will continue to think, so you could say that if I do not think, I am probably not.”

“Whatever.” Alford was not going to press too hard at this stage. Lyman only got to be a Roman Senator once, after all. If he was a Roman Senator. Alford couldn’t remember the name of one who had actually slit his wrists and bled to death in a hot bath. Something about it seemed unlikely. All those tendons.

“There’s another thing you ought to know,” Lyman went on. He stopped watching the crimson ribbons and looked instead through the vapors at the ceiling. Small drops had condensed on the ceiling. One hung in a strange puckered sack for a moment before falling into the tub. When it hit the surface of the water, it created a small stalk of liquid that settled into rings. Surface tension, Lyman thought he said or said he thought, does that. Water again. And he was trying so hard.

“Another thing?”

“Peanut butter.”

“Peanut butter.”

“Only two percent water. Food with lowest water content. As opposed, say to diet colas, which are one hundred percent water. Another thing you may not know…”

Alford was growing uncomfortable. The bathroom was hot, and Lyman seemed unable to concentrate. That could be serious. The water was now a uniform crimson, or rather a watery pink. This, even Alford knew, was because of Brownian motion that jostled all the little hemoglobin molecules equally throughout. Only Lyman’s head, hands, and knees rose into the mist, islands of flesh (still sixty-five percent water, though).

Alford stood at the sink, washing his hands. Water running over them, taking away millions of cells of dead skin. He didn’t like to think that. “Something else.”

“Herring.”

“OK, herring.”

“Atlantic herring, 69 percent. Pacific herring, 79 percent. Why do you think that should be?”

“How should I know?” Alford complained, drying his hands. He sat on the toilet again.

“Water,” Lyman suddenly exclaimed, throwing his hands into the air. Reddish droplets sprayed around the room. “To hell with it.”

He got out of the tub and began to towel himself off. “Universal damn solvent,” he said, rubbing his rather prominent belly vigorously with the towel, which was aqua. “Medicines dissolve in it. Diseases dissolve in it. The stuff is everywhere. There are, Alford, some 326 million cubic miles of the stuff on this planet.”

“What about your Roman Senator?”

“Not a Senator, Alford. Not a Senator. Seneca the Younger, I believe, advisor to Nero, who condemned him to death. Probably unfairly.”

“He died in the bath?”

“Perhaps, perhaps. The truth here is… cloudy.”

“ But you were going out in style, Lyman. With a real flare, I have to say.”

“Changed my mind.”

Lyman taped his wrists and shrugged into his bathrobe. “Another day, perhaps. Plenty of time. To continue, the Antarctic ice cap contains around seven million cubic miles of fresh water. Since the world’s entire supply of fresh water is 9 million 68 thousand cubic miles, you can see that most of our fresh water is frozen at the South Pole, where it won’t do any of us any good. Of course, now that the ice caps are melting… “

He tied his belt and faced his companion. “Well, compared to the Antarctic ice cap, Alford, you and I are mere drops in the bucket.”

He opened the door. “Come on, let’s go get a drink. I’ve worked up a terrific thirst.”

***

Rob Swigart has a doctorate in comparative literature. Since then he’s worked as a technical writer, computer journalist, designer and scriptwriter for computer games. With Portal for Activision, he pioneered computer narrative and later served as secretary of the board of the Electronic Literature Organization. For a dozen years, he was a Research Affiliate at the Institute for the Future.

Because of his lifelong interest in the deep past, he described this work as a kind of future archaeology. In the first decade of the 21st century, he turned his attention full time to archaeology, and wrote two textbook-novels, Xibalba Gate: A Novel of the Ancient Maya and Stone Mirror: A Novel of the Neolithic, while a visiting scholar at the Stanford Archaeology Center. Due in December 2019, from Berghahn Books, is a collection of short fiction that chronicles mankind’s mistaken adoption of agriculture called Mixed Harvest. He is also the author of The Lisa Emmer series on Kindle.

Photo: Rob at the site of Henry David Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond, Concord, Massachusetts.

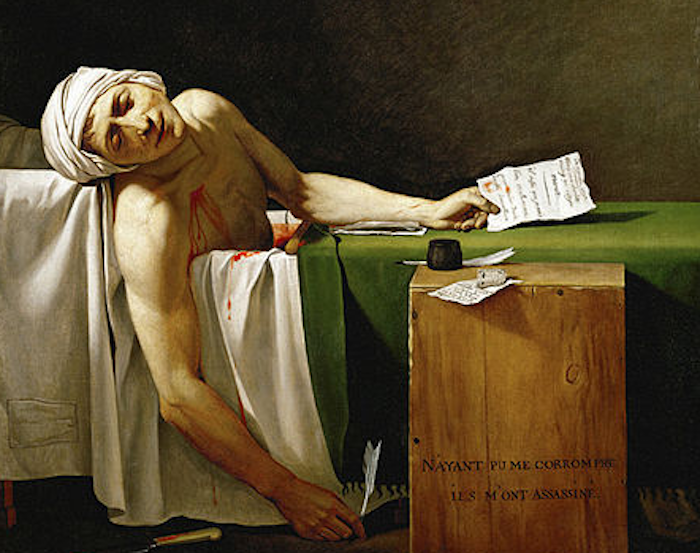

Featured image: “The Death of Marat” by David (1793). Marat, an anarchist, was stabbed to death in his bathtub by Charlotte Corday, who was guillotined for his murder.