I

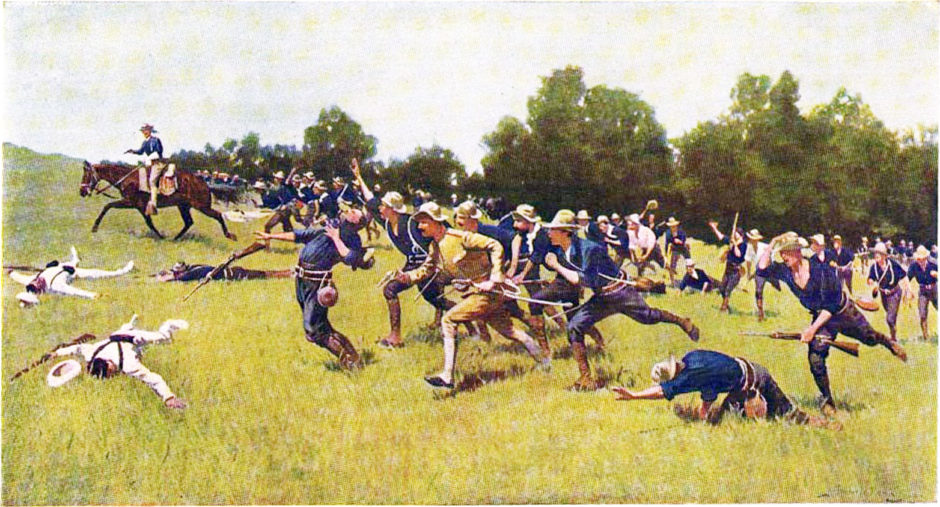

The Cuban sun baked through Pat’s sweat and blood-soaked uniform. He lay in the tall grass halfway up the first hill, surrounded by dead and dying soldiers, patiently waiting for a litter-bearer that would never come. The hole in his side oozed, the flies already crawling on his hand, biting his flesh. He had swatted at them at first, but now he had no strength to shoo them away.

He could not decide where to put his hat. The sun burned through the felt regardless where he laid it. He settled on putting it over his face, the stink of his own sweat tickling his nose as he closed his eyes. His head swam and he felt the urge to be sick.

Echoes of gunshots came to his ears, less numerous now than they had been an hour ago. The occasional gruff report of an American Krag, followed by the sharp replies of a Spanish Mauser, tickled his memories. Something about the single thwack of the .30-40 seemed familiar, almost comforting. Something reminding him of his childhood in Texas. There was a pattern to it. A rhythm. One shot—thwack. Pause. Another shot—thwack! Pause. Thwack! Pause….

II

Thwack!

The axe swung in an arc over his father’s head, parting the air in a low whooshing hum, before splitting the mesquite log with a gruff cough-thwack!-that echoed off the barn. The two pieces of the log fell to either side of the block and the man reached towards the piece on the right, tucking the axe underneath the useless left arm to retrieve the wood. He set the partial log on the block, took the axe in his right hand, and swung again in a powerful stroke, splitting the piece further in two.

Pat had always been awed, and secretly afraid, of his father’s ability to do everything one-handed. Whether splitting the stone-tough mesquite wood or putting the mules in their traces and guiding the plow, the man never gave the hint of annoyance or inconvenience. Pat had once seen his father scare off a pack of coyotes with the Winchester, using the stump of his left to balance the rifle and levering with his right.

Pat had seen his father without a shirt only once in his life. Rebel had been spooked by a rattler and bucked hard, sending the man into a prickly pear. Pat had helped his mother tend to the wounds and Pat had been distracted by the broad, tree-root scars that stretched the length of his father’s left side. Pat had asked about the scars and his mother had shushed him. His father, however, gave him a long look with his steely blue eyes.

“How old are you now, boy?”

“Eight.”

“Ask me again when you’re nine.”

Pat had waited. On his ninth birthday he asked again. Again, his father paused for a minute before answering.

“Ask me again when you’re ten,” he said.

Pat had asked again when he turned ten. And again when he turned eleven. And again when he turned twelve. Each time, his father had told him to ask later.

Now fifteen, Pat found himself wondering if his father was embarrassed about his injuries.

“Woolgathering, boy?” His father standing over the block, leaning on the axe.

“No, sir,” Pat said, his face burning. He rushed to the block to gather the split wood into his arms. When his arms were loaded with the mesquite, his father turned and walked to the woodshed. He opened the door with a quick flip of the axe head. Pat stacked the wood neatly inside. The woodshed was almost completely filled, the pungent aroma of mesquite thick in the air.

“Keep four for the house,” his father said.

Pat took the logs and turned, watching his father place the axe onto the hooks inside the shed. The man picked up three logs, put them beneath the stump of his left arm, and took a fourth into his right hand. He turned and found Pat looking at him.

“What happened to your arm, Pa?”

His father looked at him for a long time, steely blue eyes considering. Then, he closed the woodshed door, latched it, and walked to the front of the house. Pat followed, his ears burning and his heart pounding. His father did not say a word as he walked inside and stacked the logs he was carrying next to the potbellied stove. Pat followed suit, rubbing his gummy hands against his trousers.

“Go and wash up for supper,” his father said.

Pat went back outside, stripped his shirt off, and pumped the handle of the well spout until a stream of cold water flowed into the barrel. He dipped his hands and face into the water, scrubbing quickly to try to remove the mesquite sap from his hands. He got most of it and put his shirt back on, shivering in the chill of the late autumn evening.

When he returned to the house, his father was sitting at the dinner table. Pat sat and kept his eyes on his plate as his mother put the rabbit and turnips in front of him. He ate silently as his parents discussed the day, the weather, and the upcoming winter planting.

“I think Pat and I’ll go to town tomorrow,” his father said. “I need to get some seed and lye.”

“We need sugar,” his mother said. “And flour if you want bread this month.”

His father looked at Pat. “Get yourself a good night’s sleep. Get the oxes traced up to the wagon first thing.”

“Yes, sir.”

Pat finished his supper quickly and put his dishes in the tub. He kissed his mother on the cheek and went to his room. He stripped to his long-johns and slid into bed. His parents continued to talk, but in such low voices that he could not understand what was being said. He was still awake an hour later when his parents went to bed.

The next morning he ate breakfast quickly and got the oxen traced to the wagon. His father came out of the house shortly after and they set off on the five miles to town. They rode in silence for the first half hour, his father holding the traces in his right hand. He kept the whip on the seat beside him. If the oxen flagged, he would put the traces in his teeth and crack the whip over their heads to keep them moving.

Pat was lost in thought when his father began to speak. At first, he thought his father was talking to himself, but after a few moments he realized that the man was telling a story.

“When I was eight,” he said, “I saw fourteen hang in Cooke County.”

III

I knew we was at war with the Yankees, but didn’t really know what that meant. Nothing seemed different. I went to school. I played with my friends, Jesse and Little Ben. The harvest was in full swing and Pa and I was spending the evenings walking the rows and picking the pole beans.

It was mid-season when I noticed that Ma and Pa whispering whenever I came into the room. They’d go quiet and send me back outside to play or to fetch some wood. Sometimes, I’d wake up at night to men talking loud in main room saying things like “conscription” and “Union League.” I’d crawl out of bed and look out from behind the door. Ma would spot me and put me back into bed. I knew something wasn’t right.

One morning the state troops came for Pa. Pa argued with them at the door. Ma tried to push me into my room, but she stopped when one of the men with stripes on his sleeves hit Pa with the butt of his rifle. Ma screamed and ran at the men, but the one with the gold on his shoulders pushed her back into the house. They dragged Pa way in irons.

The next day, me and Ma put on our Sunday best and walked the courthouse. She told me we was gonna stand tall for Pa.

“Pa ain’t done nothing wrong,” she said. “We’ll show them he’s a good man with a family.”

The state troops was standing outside the courthouse. At first, they didn’t want to let us in. Ma showed them a piece of paper and argued with the one with stripes on his sleeves, the same one who had hit Pa. Other people had gathered ‘round the courthouse and were shouting. A rock hit my ear and I turned to see who it was. Big Ben, my friend’s pa, was pointing at me.

Little Ben was behind his pa. He threw a rock, but it missed me and hit one of the troops. They let us in after that. They was okay with us being stoned, but they wasn’t so keen on being stoned themselves.

The courthouse seemed huge. The tables and chairs was all pushed aside and people was lined up along the walls. In the middle of the room they had Pa and all our neighbors chained together. I called out to Pa, but one of the troops clouted me on the ear.

“Shut him up,” he said to my Ma, “or I’ll shut him up for you.”

Ma pulled me close.

“That what they teach you to do in the state troops, Frank Dickson? Beat on women and children?”

“They teach me to kill traitors,” he said. “Decide which side you’re on, Sally.”

It was a long day. One man was saying that Pa and all the neighbors were Unionists and were planning an attack. Another man kept saying that Pa and all our neighbors were good men trying to make a life just like everyone else. Many people shouted. Some cried. Pa kept silent.

At the end of the day, the judge said that seven of our neighbors would hang. The womenfolk tried to go to their men. Someone was calling the verdict out of the window. Ma was pulling me through the crowd trying to get to Pa, and Pa was trying to get to us. The troops were trying to get the seven men out of the front doors.

The doors broke open and people from the outside ran in. They didn’t care who they grabbed. Pa pushed Ma and me away as they reached him. They picked him up and carried him out of the doors with thirteen others. Pa fought to get away and they hit him with an axe handle. His nose broke and blood ran down his face as they dragged him and the other men outside.

Me and Ma tried to get to Pa, but the crowd was too thick. We ran back through the courthouse to the back door. It was already dusk. A bonfire had been set by the hanging trees. The crowd had already dragged Pa and the other men to the branches and were looping nooses ‘round their necks.

They hoisted each man onto a branch and tied the rope to the trunk. Pa’s feet were kicking and he was pulling at the noose. We reached the tree and tried to untie the rope. Big Ben pulled Ma away from the tree. Ma clawed at his face and Big Ben shoved her to the ground. He drew his revolver and pointed it at Ma. His mustache was bristled like needles. The blood from the scratches flowed down his chin.

“Go on and do it, Benjamin Talbot,” Ma said.

Big Ben hesitated for only a moment before he shot her between the eyes. He grabbed me by the hair and dragged me to his hoss. One of the troops stopped him as he started looking through his saddle bags.

“What are you doing, Ben?”

Big Ben nodded at the trees. “Gonna string him up like his Pa.”

“You can’t hang a boy,” the trooper said. “It ain’t right.”

“Spit on what ain’t right! My boy’s been at their house while all manner of Unionist talk was going on. It’ll be a lucky thing if he don’t turn out a Yankee-lover like this one.”

“You can’t hang him,” the trooper repeated.

“You gonna stop me?”

The trooper looked at Big Ben and then down at me. He looked over his shoulder at the crowd and the hanging men. He said, “Tie him up.”

“Why?”

“Make it look like you was trying to keep him from setting the others free. When it’s all settled down, we can figger out what to do with him.”

Big Ben sniffed and pulled the rope out of his saddle bag. He tied it ‘round my wrists and then made a loop in the other end. Before the trooper could see what was happening, he threw the loop over the saddle horn and slapped the hoss’s rear. The hoss took off and I was jerked so hard my right hand came free. The rope cinched over my left wrist and I was drug through the dark.

I couldn’t see where we was. I kept slamming into mesquites and rocks. Something ripped through my clothes and tore up my left side. I felt my shoulder pop, and my left arm went numb. When the hoss finally stopped, I just laid in the dark. I couldn’t even cry. I just wanted to die and get it over with.

I heard another hoss coming up. The trooper who had been talking to Big Ben came to me and dismounted. He cut me free and picked me up. It hurt so much that I screamed and everything went black. I woke up a few days later at my grandma and grandpa’s. The local doc had stitched me best he could.

I don’t remember much from those first few months after the hanging except the hurt, both out and in. I got better, but the pain never really went away.

IV

His father fell silent. He took a long drink from the canteen. He handed the canteen to Pat without looking at him. Pat did not take it. He felt sick.

“Why?” he asked. “Why did Big Ben drag you, Pa?”

“Drink,” his father said.

“But—”

“Drink, son.”

Pat took the canteen and drank. The water was cool and he realized to his surprise that his throat was parched. He took several long pulls before handing it back to his father. The man put the canteen back behind him, put the traces in his mouth, and cracked the whip over the flagging oxen.

“Why, Pa?”

His father stared forward.

“I asked myself the same question. Maybe he was scared I’d grow up and kill ‘em all. Get my revenge, like. Maybe he was scared that if he left a witness, they’d all hang next. It weren’t ‘til I married your ma and you were born that I understood. He was just scared.”

“Scared of what, Pa?”

His father looked at him, the steely blue eyes calm.

“Just scared, son. People are like hosses. Somethin’ spooks them and they start runnin’ not knowin’ what they’re scared of. They’ll kick an’ bite at everything to not be scared anymore.”

“But why’d you stay?”

His father looked back towards the road and was silent for a moment.

“Because I was scared.”

“But…if you was scared—”

“I ain’t never run from what’s scared me.”

“But—”

His father pulled on the traces and the wagon came to a stop. He turned in his seat to look at Pat. He put his good hand on Pat’s shoulder.

“Patrick,” he said. “God may have made this world, but he let the devil rule it. And the devil rules by puttin’ fear into folk. Anytime you do or don’t do somethin’ because you’re scared, the devil wins.

“The devil ruled in Cooke County that night, and all those folks did things they wouldn’t have done if it if they wasn’t scared. If I’d left, I’d have been letting the devil rule me. I’d have been no different than the men who hung my Pa. I’d have been no different than Big Ben.”

Pat considered for a moment, and then nodded. He said, “I think I understand, Pa.”

“No…you don’t,” his father said. “But you will.”

He turned back towards the front of the wagon, picked up the traces, and flicked them. The oxen began moving again, pulling the wagon slowly behind them. Pat watched the mesquite trees as they passed them.

V

A shuffling sound crept to his ears, growing louder by the moment. Pat lifted the hat off of his eyes to see one of the Buffalo Soldiers running towards him, his dark skin shining with sweat as he bounded through the high grass. The scarlet cross on the man’s arm drew Pat’s eye. His chuckle turned into a spasming cough that shot hot needles of pain through his side. He wiped his mouth and stared at the claret smear on his palm, his vision graying.

The devil didn’t win, Pa, he said. But damned if he didn’t try.

* * *

M. James MacLaren lives in Connecticut. He is an authority on shamanism, esoteric histories, and supernatural theories. A trained naturalist, he often disappears into the dark places in the world where fear and good sense keeps others at bay.

M. James MacLaren lives in Connecticut. He is an authority on shamanism, esoteric histories, and supernatural theories. A trained naturalist, he often disappears into the dark places in the world where fear and good sense keeps others at bay.