The Publisher of EnvelopeBooks

Proves You Can Judge A Book by Its Cover

The art of creating a distinctive publishing brand among a miasma of publishers

Ever wonder why there is no authoritative, independent resource for seeking out books like there is with IMDB for movies? (Well, like IMDB used to be, anyway.) It surely isn’t Amazon, nor is it Goodreads, which Amazon took over in 2013. A year earlier, a publishing entrepreneur filled that void in the UK . . . we interviewed him to learn about his experiences and views of the publishing business.

In 2012, Stephen Games started a magazine connecting publishers’ books with readers and named it Booklaunch , which he says is, “now the highest circulation books magazine in the UK . . … Tabloid-size pages allow publishers to place 1,500-word extracts from new books, and our readership is almost entirely made up of subscribers to the New Statesman and The Spectator.”

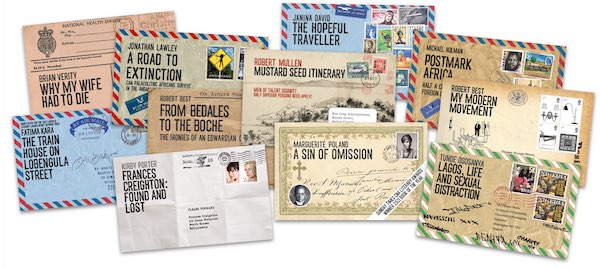

Following on the success of Booklaunch, in 2020 Stephen launched his own publishing house, EnvelopeBooks, publishing both fiction and nonfiction with postal-envelope themed cover designs. A separate imprint, PostcardBooks, publishes memoirs. He says, “What is a book but a letter from a writer to a reader?” Fictional Cafe asked Stephen to tell us about this unique publishing startup and how it’s faring.

FC: You publish the biggest books magazine in the UK—Booklaunch, which appears quarterly in a print run of 51,000. Why did you decide to launch a publishing company off the back of it?

SG: Booklaunch runs excerpts from important new books that probably aren’t commercial enough to get reviewed in the mainstream press but deserve to be better known. (Think of us as a highbrow Reader’s Digest.)

Our readers started asking us for help in getting published, and after a few issues in which we promoted their manuscripts in our pages, I realized we could help them more by starting our own imprint—and EnvelopeBooks was born. There are lots of writers out there who need help, and they get terribly abused and exploited by other publishers.

FC: No kidding! The EnvelopeBooks titles I’ve read confirm your slogan, “We aim to publish intelligent, ambitious, high-quality writing with something new to say.” Are you avoiding genre fiction, e.g. spy novels, romance, thrillers? Do you find that a sustainable business model? How do you find or attract your type of author?

SG: I’d love our novels to go mass market; they’d help fund all our other books! At the London Book Fair in April this year, I was offered a novel by an author who said he was going to be the next John Grisham—and maybe he will. But the manuscript he sent me sounded like a John Grisham knock-off, so I let it go. The thing is, I’m not interested in copying what other publishers churn out. I’m interested in stuff that’s more ambitious than that—and it’s my job to make it work.

FC: Is that sustainable?

SG: I don’t know yet: it’s only been 30 months since our first book came out, and we’ve only just got our global sales operation established, so ask me in a year’s time.

FC: Your book covers look like envelopes. That’s unconventional.

Your website pitch is unconventional too. You encourage authors to submit work without explaining who they are, why they wrote what they wrote, what their background is, who they want to reach, etc. Why don’t you put up the same filters that other publishers and agents do?

SG: Most mainstream publishers and agents are either so overstretched or so self-important that the first thing they do is force aspiring writers to jump through hoops—or look elsewhere. Why do that? You don’t go shopping and see signs in the window saying, “Come back in six months’ time” or “We’re closed except to established customers.” I prefer to be nice to people. Make them feel welcome. Deal with their inquiries promptly. I don’t need them to defend themselves or their background or their ambitions. Just send me the goddam book and let me see for myself.

FC: You have more than one imprint: EnvelopeBooks and PostcardBooks. What’s the difference between them?

SG: EnvelopeBooks is for books that are more likely to have commercial potential and that we try to get stocked in bookshops and reviewed in the media; PostcardBooks is for titles that will probably only have a readership of friends and family, and which we make available online but don’t try to get into shops.

FC: How is the publishing experience industry in the UK different from or similar to the US?

SG: US independent bookshops are more adventurous than those in the UK and have much greater engagement with the communities they serve. That’s very attractive to us, and one of the reasons we decided to jump from the UK into the US market. In the UK, independent bookshops are very fragile and end up focusing on the most obvious titles—the ones produced by the Big Five. US independents seem more assured of themselves and less risk-averse.

In addition, the US is of course a way bigger market—about five times larger than the UK—and our US sales team is proportionately bigger too.

FC: Are you open to submissions from authors outside the UK?

SG: Absolutely! One of our most recent books— Tunde Ososanya’s Lagos, Life and Sexual Distraction—is a collection of short stories by a TV reporter who works for the BBC in its West Africa bureau, Lagos. We’ve just published a novel called The Train House on Lobengula Street by Fatima Kara, a writer who grew up in the Indian Muslim community of what is now Zimbabwe, and lives half the year in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Our second book, A Road to Extinction, a nonfiction work, was written by Jonathan Lawley, the grandson of the man who was deputy commissioner of the Andaman Islands, off the coast of Myanmar in the Sea of Bengal.

FC: You’re an indie in American parlance. There are several types: some publish like the traditional houses, while others charge authors varying rates. What, if any, are your fees?

SG: We offer conventional contracts for books with sales potential; we’ll charge fees for books where we’re less likely to recover our costs. But we’ll adopt whatever model works. We’ll soon be republishing a book about the Second Gulf War and its aftermath, called The Martyrdom of Ahmad Shawkat, written by Michael Goldfarb, who covered the war for NPR. During the three years or so that I spent in LA in the 1990s, I admired Goldfarb’s work and I’m doing this book as a thank-you to him.

Normally the publisher carries all the costs and gives the writer royalties of 10% after it has paid off its production costs. We offer that as a model but we offer another model where the writer pays a share of the up-front costs and we then split the returns 50/50. Some writers like this better; others prefer the standard model.

Where we charge, it’s based on word count but typically comes out at $2,500 to $3,000, which typically includes meticulous copy editing and proofreading, something lots of publishers are shamefully lax about.

FC: Do you personally select each book for publication, or are they chosen by an editorial committee?

SG: It’s all down to me—I’m God.

FC: (Haha!) Do you commission works from selected authors, or do you rely mostly on over-the-transom[1] submissions?

[Editor’s note: “over-the-transom” means the writer slips into the publisher’s building in the dead of night and pushes his unsolcited manuscript through the small ventilation window above the editorial office doorway.]

SG: Most of our books come to us via Booklaunch, but as we get more established I’ve started reaching out for books I want to publish. For example, the moment I heard about Donald Trump’s fourth indictment, I contacted a reporter in the USA to write the introduction to a collection of verbatim Trump material that I want to bring out. But everything’s serendipitous. I meet someone by chance or hear someone on the radio, exchange notes with them, and hope something comes of it.

The veteran explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison took me to lunch at his smart London dining club a couple of months ago and offered me a book about environmentalism; I ran an interview with the TV scriptwriter G.F. Newman in the summer edition of Booklaunch and we got on so well that he offered me a novel of his.

FC: How many books per year do you publish? How long does it take for a new title to appear?

SG: We’re doing about a title a month at the moment; alongside Booklaunch, that’s the most I can manage. It’s not massive, but it will probably grow as we get better known. For now, I believe in groping my way carefully, taking advantage of opportunities as they come up, but not over-reaching. Enough of what we’re doing is conceptually demanding; the last thing I want is to take on additional risks.

As far as timing is concerned, it’s at least a one-year turnaround for commercial books. Our PostcardBooks titles—the non-commercial ones that go straight online—can be done much more quickly, but our EnvelopeBooks titles typically take at least six months to prepare, and then the sales team asks for another six months to get them known to bookshops and buyers.

FC: Do you provide marketing services for your authors?

SG: We advertise in trade magazines, we have a social media manager who sends our books out to bloggers, and we employ a publicity consultant who promotes us on Instagram and TikTok. We also promote our titles at trade fairs and in the trade press, so bookshops get to know us better.

Without help from the author, however, mass-market advertising is beyond our means. In the case of the first of our Gay Street Chronicles novels, set in Bath in the 1830s and titled Belle Nash and the Bath Soufflé, the author William Keeling decided he wanted to promote it himself and we designed a massive backlit poster for him which ran for ten weeks at the railroad station in Bath.

FC: What an excellent idea. Your covers are distinctive as well. How did you arrive at the idea to use envelopes and postcards for cover designs?

SG: I felt it was important to demystify publishing and I came up with this idea that a book is really only a letter from a writer to a reader. Everything grew from that.

FC: What is your publishing vision for the future?

SG: Survive, grow, keep doing interesting books and covers—and take over the world. I want our books to be bought and read by everyone: that’s why we’re not a niche publisher. But I also want our books to be enjoyed as visual icons. Our covers have an aesthetic about them, the way ECM records did in the 1970s and ’80s. They’re great as accessories. I guess that’s why I have no interest in digital publishing; a digital book has no physical presence. You can’t show it off in the way you can show off a print book. That’s why EnvelopeBooks are so cool.

FC: That’s a wonderful analogy with ECM’s record album jackets.

FC: What do you think the publishing business will look like in 5, 10 years?

SG: Oh, it will get worse. The Big Five will have become the Big Three, senior executives who just want to make money will become even wealthier, and those who love books will either be destroyed by the industry or escape to start up their own operations.

There’s probably a window of about ten years for printed books. After that, the book as an object will become meaningless. My 17-year-old daughter doesn’t read—doesn’t know what a book is! I have 7,000 books in my house and I’d always thought of them as my legacy to her. Much hope! Her idea of entertainment is her iPhone.

FC: As a died-in-the-wool printed book lover, I find the phone a very inadequate replacement to the information transfer one experiences when reading the printed page. And I’m more optimistic about the book’s life span. As a young editor in the 1970s, I vividly recall attending a conference entitled “The Death of The Book.” Yet aren’t bound books, again, outselling e-books.?

SG: I don’t know, but I don’t believe a word the publishers say in their press releases. During the Covid lockdown, there was all this stuff about how book sales had soared; it was speculative nonsense. Publishers are finding the new world very tough. In the last three years, two major book distributors have gone out of business in the UK and another is having difficulty making payments. As with anything, if you want the truth, follow the money.

FC: Tell us about some of your forthcoming books and covers.

SG: We’re about to publish our first filmscript—Princess Brr-Rainy—because why not produce stories in movie format? This particular title is based on an Andrew Lang fairytale from the 1890s—probably his best—but updated, of course, in the style of “Shrek” or “Frozen.”

By contrast, we’ll be publishing next year A Question of Paternity, the troubling memoirs of US television reporter and host David Tereshchuk, who has gone round the world unravelling the truth about international politics but been unable to discover who his own father was: an information vacuum that in his younger years sent him off in a spiral of addictive and anti-social behavior.

FC: What else?

SG: A fascinating book called Where’s the Harm? by a Cambridge academic from New Zealand that invites readers to assess the legal assumptions events in her life have given rise to; and a book called The Rest v. the West by a highly-placed tobacco executive who advances various notions which I do not agree with but am happy to see explored, such as the good his industry has supposedly done in developing the economies of emerging nations like Vietnam; and a novel about a medieval lawyer with overtones of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose.

FC: Very interesting! We would love to do an excerpt from one of them!

SG: Any time!

FC: On the need for a new business model for the publishing industry we are in complete agreement, Stephen. Thank you for taking the time from what is surely a very busy workday to share your thoughts.

SG: Thank you, Jack. You’ve provided a wonderful platform for us to review where we’ve come from and where we’re headed. Happy to come back to you and talk more. And do send any would-be writers our way: our doors are always open.