Each time is the same as before, but each time feels new. He and Grace hold hands in the hallway and stare at Destiny through the streakless glass. Grace chose the name and to see it written on that little plastic band in official type makes her happy. And why shouldn’t she be? The delivery went great. Destiny is perfect. Everything is perfect. Well, maybe not “perfect.” It’s true, Destiny was unplanned. True, he and Grace don’t have their own place to bring her home to. True Grace’s parents are actively unsupportive of their child and her teenage boyfriend bringing another child into the world. But none of that matters. Grace and Destiny are happy and healthy. That’s what matters. This moment matters. He wishes he could slow time down and stay in this moment forever.

But he can’t. Because suddenly, and just like every time before, the sounds of thumping from a room at the other end of the hallway intrude. The room is bright, but with every thump everything else seems to dim. The light above Destiny goes first, and soon as it’s gone, he can no longer remember her face. The hallway light is next and the thump that darkens it echoes like a horn in an empty tunnel.

The hallway is dark but for the room and a dimming light above Grace’s beautiful, pained face. Then with a final thump she’s gone and both the dark and the light engulf him.

**

He wakes up panting in the sun. His breath, visible in steady patches, follows one after the other like exhaust from a semi. The seven o’clock church bell causes the ground beneath him to thump and vibrate. He squeezes his eyes shut and pulls the blanket over his head. This is the bad part. The start of his day. Each time is the same as before, but each time feels new.

It isn’t new, though. It’s a routine. And soon as his heart stops racing, the routine will continue. He’ll get up, clean up, go out and grab something to eat, then head off to work. This morning, like every other, he doesn’t want to do that last part. He wants to sit and remember the dream, but he knows he can’t. For one thing, the more he thinks of it, the less he remembers. For another, if he didn’t work, he wouldn’t survive. He’s like every other New Yorker in that way. Almost every other anyway. Most New Yorkers hate their jobs but need them. He needs his, so…

He opens his eyes and pulls his blanket down. The seventh and final bell toll has finally stopped echoing. The sun warms his face despite the biting cold that chills his ears and body. The temperature on the clock claims it’s twenty-eight degrees, but he’s doubtful. It feels much colder. Nevertheless, one of the few benefits to his work is that he can do it either outdoors or in.

He forces himself to sit up, and folds the blanket down to his knees. Sometime during the night, something must’ve taken a crap in his mouth, and he turns to the garbage and spits. He grabs a bottle of water beside his leg, pours a little in his mouth, then spits that out too. For a moment he considers going back to bed, but maturity prevails and he slides out from under the blanket, folds it carefully and stows it away. Gathering his things for work takes a minute, then he steps out to the street and looks for breakfast.

**

He’s not picky – most people in his profession aren’t. When you’re always on the go, you eat what’s available. Still, he’s conscious of what he puts in his body, so he tries to avoid eating fast food too often. The problem is that diners and restaurants aren’t always an option. Sometimes he goes to McDonald’s or Dunkin Donuts but if possible, he’d rather a fruit stand. During the winter in New York City though, there aren’t many fruit stands to find, so more often than he’d like for the past few months he’d go to a fast food restaurant, order a meal and a large iced tea (hold the ice), sit down and plan his train ride for work.

There are a bunch of things he considers when deciding which train to use. The day of the week for instance. It’s Saturday which means most trains are local. It also means that most nine-to-fivers are at home watching Bugs Bunny or Mickey’s Playhouse or whatever it is families watch nowadays. Taking into account the day, the second thing to consider is the weather. He isn’t sure what the date is but there are bright colored bunnies and eggs in the store front windows, which means it’s approaching spring and the weather is likely to be more comfortable later in the day. Which is good. The third consideration is dinner. Depending on where he plans to have dinner, he needs to take a train that will leave him in the area. Lastly, he considers the others. His coworkers. His competition. It’s an annoyance for everyone involved if you take the same train as the competition at the same time. It’s awkward and tense and ultimately a waste of time. Realistically, there’s no real way of knowing whether or not he’ll be on the same train as one of the others, but he can make logical guesses. Everyone comes to the same conclusion about which train on a cold weathered Saturday morning would get you to customers fastest, but if everyone takes the same train, it ends up being a slow day. So he doesn’t take those trains. He takes the train that takes a little longer to get to the clientele but has less competition. A means to an end. It’s good to get to as many customers as fast as possible but realistically, what’s the rush? He’s not going home to anyone.

He finishes eating and has chosen a train, then looks around for a clock. He owns a watch but doesn’t wear it because the battery died. Occasionally, he considers having the battery replaced, but then asks himself, what’s the point? People are always willing to give him the time of day when he asks. And even if they didn’t, there are huge digital and analog clocks on buildings all over the city. For most people, watches aren’t a means of telling the time anyway. They’re a fashion statement. But that’s not him. For one, he can’t really afford to spend time or thought or money on fashion. And two, it would be self-defeating. Customers don’t really like to see him wearing jewelry. And also, again, what’s the rush?

McDonald’s has a clock on the wall, with Ronald standing in the middle with his red hair at twelve, his red boots at six and his arms as the hands of the clock. There’s no seconds hand and he stares at the clock waiting to see if the minute hand moves because he doesn’t believe the clock is working. It reads the time as nine minutes after nine and that’s impossible. Unless he’s crazy.

After about twenty seconds the minutes hand does in fact move and he starts to worry. Time has escaped him before but never like this. There were times when his memory was black and some time had passed that he couldn’t account for but this wasn’t that. He remembered walking over to McDonald’s, waiting in line behind the two individuals and one couple ahead of him, ordering breakfast, then sitting down. There are no black spots.

He feels his pulse in his chest and is suddenly conscious of his breathing. He leaves his coat on his chair, but takes his backpack with him, and goes to the cashier. She’s pretty and polite and professional and she smiles whenever she speaks. She’s probably young enough to be his daughter but he figures she calls him sir not out of respect for his age but because she was probably taught to call all men “Sir” and all women “Ma’am,” until a woman gasps and tells her that she’s not old enough to be a ma’am and they settle on “miss.” She smiles as he approaches her and she obviously remembers him because every employee in every establishment he enters remembers his type. They’re probably taught to do that too. When he reaches the counter, she leans forward slightly. Her posture says, I’m ready to help you because I’m good at my job. Not for any other reason. And that was probably something she learned on her own because she’s so pretty and men are so easily confused.

She says Hi and smiles and he smiles back.

“I’m sorry,” he says. “Is that the right time?”

The cashier squints at the clock and frowns then she takes her cellphone out of her pocket with her left hand and looks at the time, even though she’s wearing a watch, then looks at the clock again.

“No, Sir. That’s not right. It’s an hour fast. It’s 8:10 right now.”

He exhales a breath he hadn’t realized he was holding and tries to relax but he’s mad at himself. He’s always so quick to assume he’s going crazy. Why? He isn’t. Shaking his head he thanks the cashier and she smiles in return, says no problem then looks behind him and asks if she can help the next guest.

He moves slowly back to his table, puts his backpack on the floor beside the chair and sits down. Staring out the window, he puts his arms on either side of his tray and starts to scratch his palms with the fingers of his loosely closed fists, slipping into dark thoughts. Then he stops himself. This is stupid. He’s not doing this. Not now.

He stands again, quickly, conscious that if anyone is watching, he probably looks crazy. But you’re not crazy, he assures himself. You are NOT! He throws his coat on, then his backpack. He dumps his tray but hangs on to the cup. At the fountain drinks dispenser, he dumps out the remainder of his iced tea. With napkins from the condiments station he wipes down the inside of the cup until it’s dry. He dumps the used napkins then grabs a handful more and puts them in his pocket. And that’s it. Breakfast is done. Time to head to work.

**

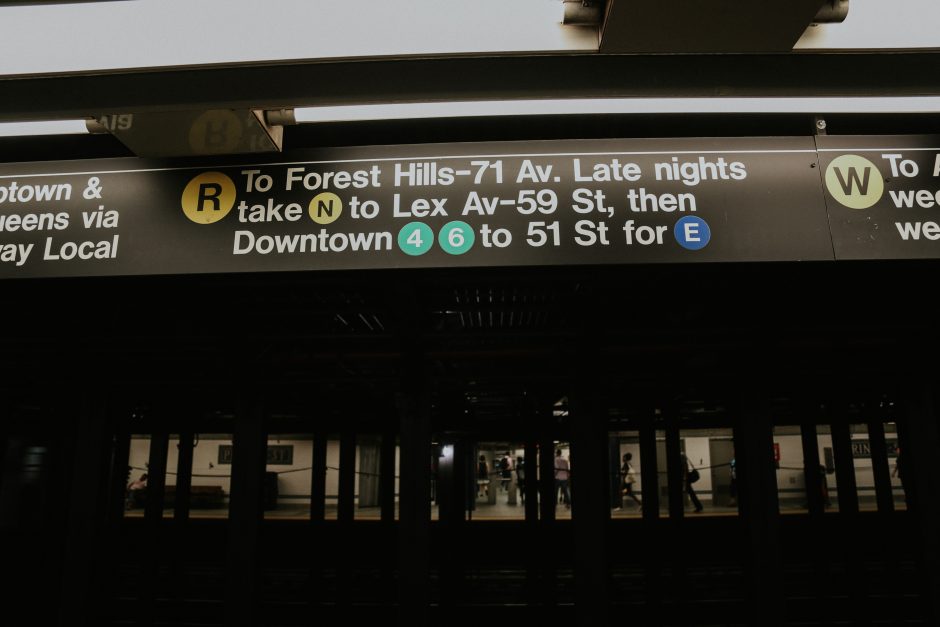

Back on the street, the weather is already noticeably warmer than when he woke up. He looks around for the closest train station entrance. There’s one on the corner and another across the street. Traffic is light but steady; it’s a Saturday morning but it’s also Manhattan. He’s pretty sure he needs the entrance across the street but because of the traffic he goes to the corner to double check. The sign on top of the stairway leading into the subway says: Prince Street Station Downtown and Brooklyn. Enter with or buy MetroCard at all times.

He was right. That won’t work. Entrances that require a MetroCard at all times have floor to ceiling turnstiles. He waits at the curb for the light, but sees an opening and slips through a gap made by the empty taxi’s hurrying to make it across the intersection before the light turns yellow and the occupied taxis who have no problem slowing down. Across the street, he jogs down the stairs and walks past the ticket agent’s booth to the waist-high turnstile and leans over. He checks in both directions and sees no one that concerns him. Then he steps over the pole. One giant step with his right leg then another to bring his left over. This isn’t the movies. The ticket agent in the booth behind him doesn’t scream at him to pay his fare. She doesn’t care. Why should she?

He walks across the platform toward the end. On his way there he examines the cup he’s still holding. It’s dry and clean. Screens hanging from the ceiling have a readout of what trains are coming next, second, third and fourth and how many minutes until they’ll arrive. His train is due to be there in two minutes. He finds a bench and uses the time wisely.

He combs his hair with his fingers and adjusts his clothing. He always does this on the way to work before he meets with customers. He isn’t one of them, but if they are going to give up their money, they’d prefer that he did his best to at least look like one of them. An announcement that the R train is arriving and a warning to stand back and stand clear comes through the speakers near the bench. He stands and rubs his hands down his sleeves and pant legs as he walks to the yellow safety stripe. The train roars into the station but slows as it reaches the other end of the platform before finally coming to rest with a pair of doors directly in front of him. From what he could see through the windows as the train passed, there are a decent amount of people on board. Excellent.

When the doors open, he steps inside and looks around. There are eleven others in the car. Nine already seated and two that get on with him, then find seats. No one looks at him. He walks to the middle of the car and waits for the doors to close and the train to start up again.

When it does he puts his bag on the ground between his legs, clears his throat and says, “Ladies and gentlemen, please excuse the interruption. I’m very sorry to disturb you. I’m hoping to make a few dollars so I can get something to eat. I want to sing something for you guys this morning, and if you enjoy it, please see if you can find it within yourselves to maybe make a small donation.”

And his workday begins.

***

I am a FDNY firefighter and aspiring author. I have had four short stories published in literary journals, as well as one creative nonfiction piece. My debut novel, No Man’s Ghost, was previewed here at the Café and has now been accepted for publication by Agora Books. I’ve been interviewed by Rachael Ray in Everyday magazine and by Slate for their “Working” podcast. I recently got over my addiction to chocolate-covered pretzels but now I’m pretty obsessed with deep-fried Oreos.