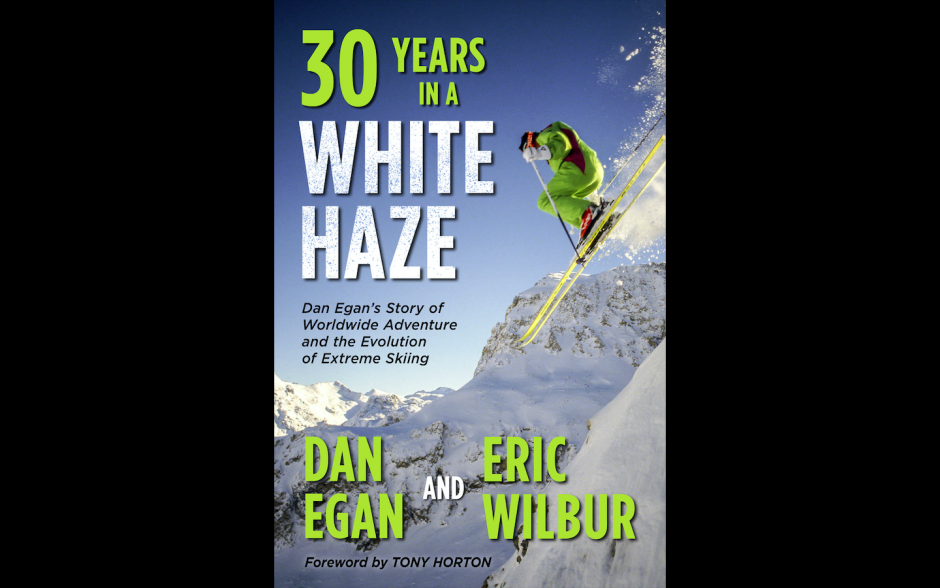

Dan Egan, with Eric Wilbur, has written a memoir which is true to its title: Dan’s three decades as an athlete in general and specifically one of the founders of the sport of extreme skiing. Thirty Years in a White Haze is his story as told to Eric. It is also the story of growing up in the Egan family and in particular becoming a world-class extreme skier alongside his brother John. We learn how they came to develop skiing abilities far beyond those of the average skier and to become extreme skiing stars in many of the legendary Warren Miller’s ski movies, ultimately arriving at the podium of the US Skiing & Snowboarding Hall of Fame in 2016.

This excerpt is the book’s Prologue, and describes what is perhaps his most challenging and life-threatening experience on one of the toughest mountains on earth: Russia’s Mount Elbrus.

Prologue

“To the roots of the mountains I sank down; the earth beneath barred me in forever.”

Jonah 2:6

Dan Egan was in the belly of Mount Elbrus, shivering in a snow cave he figured would become his tomb. Like Jonah, he ignored his inner voice and was swallowed by the big fish, a mountainous consumption to be tediously digested into an awakening.

At 18,500 feet, Russia’s Elbrus is the highest peak in Europe, a dormant volcano just west of the Black Sea and north of Russia’s border with Georgia. An estimated twenty-five to thirty people die each year attempting to summit the mountain. It’s one of the Seven Summits mountaineering challenges, scaling the highest peak on each of the world’s seven continents. Seven Summits is an exclusive club only a few hundred people have managed to join.

Elbrus has a higher annual death toll than Mount Everest, despite the list of tragic stories that emerge from the highest peak in the world, many of which have been made into riveting documentaries of triumph and loss. There were eleven deaths on Mount Everest in 2019, one of the deadliest years in the mountain’s recorded climbing history. As recently as 2016, thirty climbers were estimated to have died in attempts on Elbrus in a single year. In 2004, forty-eight perished trying to reach the summit.

The Elbrus ascent is steep and icy. Abrupt storms and sub-zero temperatures lead to frostbite and hypothermia. Its long history of bad weather has frustrated climbers for centuries.

In 1990, this was where Dan Egan found himself on Mount Elbrus, pinned down by a massive snowstorm, digging a snow cave for his life.

At the time the Caucasus mountain range, located between the Black and Caspian Seas, was still a geographical characteristic of the former Soviet Union. It was also a world away — both in distance and culture — from Dan’s home in suburban Boston, Massachusetts.

Thousands of miles to the west, the Boston public school system, which Dan’s grandfather had once helped steer though its most volatile period, was throttling down toward the summer break. The South Boston Yacht Club, where Dan had inherited a sailing passion from his father, was bustling with spring fever. It was the time of year when Dan usually made an annual pilgrimage to Mount Washington’s Tuckerman Ravine in New Hampshire, about four hours north of the Blue Hills Ski Area, itself less than half an hour’s drive from Boston, making it the ski area nearest to any major metro area in the United States. Both Blue Hills and New Hampshire were responsible for luring at least two generations of Egans into the sport of skiing.

But this year Dan was in a snow cave on Elbrus. It was his sister Mary Ellen’s birthday. His former Babson College soccer friends were gathered to dedicate a memorial to a teammate on this very same day. The Blue Hills, Tuckerman’s and home were far, far away.

Dan’s brother, John, was far below in the storm raging on Elbrus. He and his brother had traveled there with cameraman Tom Day to help document an expedition consisting of twenty-three people from nine countries. Filmmaker Warren Miller had discovered John skiing at Vermont’s Sugarbush Resort in 1978. When Dan joined John on the big screen in 1985, they soon branded themselves as “The Egan Brothers” as they chased the news on snow to places like the Berlin Wall, Yugoslavia, and the Persian Gulf War, lugging their skis along for narratives that would redefine the genre. It had become quite a ride around the world for both. That John and Dan were separated on Mount Elbrus was certainly an uncommon exception to their usual tight bond.

“Let’s follow CNN,” Dan had told Miller, a proposal for documenting the sort of skiing on film that eventually to led John and Dan’s careers paralleling the geopolitical landscape of the 1980s and 1990s. After all, as Miller would often say, “If everyone skied, there would be no wars.” What better way to deliver the peace-seeking promises of skiing than to showcase the sport on film in some of the world’s most-renowned frontlines?

By 1995, the Egan Brothers would appear in more Warren Miller productions than any others. While Dan was hallucinating, vomiting blood, and fighting for his life on Mount Elbrus, it was probably likely that somebody was enjoying watching him and his brother ski in tandem on a VHS tape, rewinding a favorite scene over and over again awed by the two skiers at the forefront of extreme sports as they hucked cliffs and skied the mountain steeps. Whenever the Egan Brothers appeared on film it was together: where one went the other would follow, skiing back-to-back and side-by-side.

But there was no John in Dan’s hastily created cave, only a Russian guide who was doing his best to save the life of an American he didn’t know.

There was a startling diversity among the climbers, many of whom had found their way to Elbrus via a sweepstakes from Degré7, the French winter sports outfitter founded by Patrick Vallençant. Recognized as the grandfather of extreme skiing Vallençant, who hailed from Chamonix, the Alps region known for its extraordinary mountain challenges, had died the previous year in a climbing accident.

This expedition to Elbrus had been coordinated by those left in charge of his clothing line. Its purpose was to film the Egan Brothers performing their outstanding extreme skiing abilities for the camera. Wearing Degré7 skiwear, they would hike up the eastern peak, which could take nine hours, then perform their daredevil skiing down the challenging 45-degree steep slopes. So far, it wasn’t going well.

A language barrier had crippled the expedition from the start, not to mention the disparity of skills and experience, which ranged from Chamonix mountain guides to recreational mountaineers. Members of the expedition had been living in a refuge on the mountain at 14,000 feet for three days, getting acclimated to the altitude. By May 2, 1990, there would be some thirteen different expeditions heading up Elbrus. It would become one of the most disastrous days in the mountain’s climbing history.

The weather had been inconsistent in the days leading up to the climb. On the night of May 1 a storm raged briefly, but broke by morning. So, with the skies clearing above, the guides decided to push for the summit. In what would turn out to be a major mistake, Dan left John and Tom behind and made way for the top of the mountain, eager for the opportunity to bask in the accomplishment. It was a decision that would ultimately, leave him stranded on the way, facing a long, cold, hungry stretch of time, uncertain he would survive.

As Dan continued his climb, lower down John and Tom found themselves turned back by the storm’s resurgence and were forced to rescue three less-experienced members of the expedition.

“The storm came up from the bottom of the mountain,” John would later say. “I saw it coming up, and when it got to us, I knew it was still going up and only getting worse.”

But the storm had yet to reach Dan above on the mountain. He was climbing with Alfred Jimenez-Segarra, a Spanish member of the expedition who had won his way to Elbrus after purchasing a Degré 7 beanie at a sports store in Brussels. At 18,000 feet, they were laboring through 20 steps at a time before pausing to catch their breath. Still, clear skies beckoned above, drawing them onward. Fooled by blind ambitionand the clear skies, Dan continued to climb, focused on the summit. Both he and Jimenez-Segarra ignored the storm threat approaching from below.

They were only a hundred and fifty feet below the summit when, rationalizing they ought to lighten their loads, they dropped their packs. The thought that their contents might save their lives never crossed their minds. Instead, as the wind increased and the ominous clouds gathered, Dan and Alfred ignored common sense.

The celebration at the summit was short. They were blanketed by a deep, dark, white haze. After hours of climbing both were confused, tired, and without their backpacks. Luckily, they were not alone. A Russian guide who introduced himself as Sasha could not believe the ecstasy Dan and Alfred displayed upon reaching the summit. Sasha probably wondered why the pair could not understand the horrific situation about to confront them all. He convinced them to immediately come with him but insisted they abandon their backpacks: to risk a search for them would also pose the risk of losing Sasha, who was also looking for missing members of an Italian expedition he had been leading. With snow swirling, breathing becoming more difficult and their senses deteriorating, Dan and Alfred chose to follow Sasha and his fellow Russian climbers, confident that they could make the refuge 4,000 feet below.

As they traversed, the situation grew worse. The group took themselves out onto the middle of a glacier, it’s hard, blue ice as solid as granite. But there were crevasses in the ice, major cracks; avoiding them led to mass confusion. Soon they were lost, although the Russians wouldn’t admit it. One of the climbers fell through a crevasse, forcing Sasha to rescue him. As the storm grew and raged, emotions bubbled into near panic. Nobody knew what to do. Nobody seemed confident in moving forward any longer.

The Russians made it clear that it was time to stop. It was time to dig in and wait out the storm.

Dan couldn’t understand what was happening or what they were doing and didn’t know how to help. One of the Russians hit him in the back and pleaded with him for help dig. So with the only tools he had, an ice pick and his hands and feet, Dan punched, kicked, and clawed his way into the snowy mountainside.

He dug, and dug, and dug . . . .

As Dan understood it, he was digging in order to build a snow cave for other members of his expedition. But he was tired, and nobody seemed to be helping despite the fact that he was building it by himself for three other people. Dan became frustrated and grew even more tired. He returned to the cave and started kicking again, unsure of what everyone else was doing to take shelter. Nobody tapped him on the shoulder and asked him to rest. Nobody offered to help him.

After digging alone for four and a half hours, Dan laid down in his snow cave. Snow was piling up outside, reaching five and a half feet. Wind was whipping at more than 100 miles an hour. Dan was vomiting blood and began experiencing hallucinations when, out of nowhere, Sasha dropped into his cave.

“I was having a white-light experience and it got interrupted by a six-foot-four Russian,” Dan said.

Dan Egan was in the belly of Mount Elbrus, swallowed by a Jonah’s whale in the form of Elbrus’s mountain peaks. It was climbing and skiing upon such mountain peaks that he had previously discovered such a purpose, a calling, as he considered it, to aspire to the highest level of success in his chosen sport, extreme skiing. And now he was confronting this calling on quite different terms: surviving a storm the likes of which he had never experienced.

Destiny? Perhaps.

“Our path from Boston to the highest peaks around the world was born out of a combination of how our parents raised us: to be independent, confident and steadfast in our pursuits,” Dan said. “Plus, all of that mixed with our personal connections from our childhood into our twenties, just because we loved to ski and were willing to risk career, relationships, and security for the simple pleasure of gliding on, over, and through snow.

“It has always amazed me how our pursuit expanded before us at every turn, even when it was hard or the path forward was unclear due to financial reasons, or the normal pinnings of other people’s expectations of how life should be, rather than what life could be.”

Because, according to Dan, there’s no other good reason why two kids from Milton, Massachusetts would go on to ski around the world, become icons of the Alpine community, and define a generation of extreme sports to follow.

“I was like a dog with a bone,” Dan said. “Once I saw what my brother had done with his move to Vermont in the 70s to be a ski bum, that vision of breaking outside of the boundaries of a ‘normal life,’ I wanted to taste it too, soak it all in and blow it wide open into something bigger. The idea that I could do it with him, my older brother, subconsciously was the motivation behind it all.”

The Egan Brothers were extreme skiing in the 1980s and 90s, doing for the sport. Extreme skiing demonstrated a fearless energy that spoke of, and to, the Egans’ sense of adventure. With the help of the emerging videotape machine—what the following generation would experience with YouTube and GoPro camera technologies. The VHS videotape moved watching a film from the theater into the home, changing the way viewers not only consumed skied a mountain as a form of entertainment, but learned more exciting ways to ski themselves.

Dan and John helped bring the extreme mantra from the mountains to Madison Avenue. Cameras followed the Egans to places never skied before. They made first extreme skiing descents in Turkey, Canada, and Greenland. They used their love for skiing to inspire peace in places like Yugoslavia, Romania, and Russia. To this day, they are considered among the most influential skiers of their generation.

It was not only his love of extreme skiing but his heartfelt desire to be an emissary for peace, love and understanding that, ultimately, brought Dan to Mount Elbrus, where he found himself in a snow cave facing death, as well as coming to terms with the realities of his career choice. Instead of achieving the personal and career success he had anticipated, it would turn out to be the beginning of everything else, as he would one day discover.

“And the Lord commanded the fish, and it

vomited Jonah onto dry land”

Jonah 2:10

***

Dan Egan is a pioneer of extreme sports, world-renowned for his big mountain skiing on the international stage. He has appeared in more than a dozen Warren Miller ski films and is known for traveling to the most remote regions of the world to ski and chronicle the geopolitical landscape of the late 80s and 90s. In 2001, Powder Magazine named Dan Egan one of the most influential skiers of our time. He was inducted into the US Skiing & Snowboarding Hall of Fame in 2016. Dan Egan is also an award-winning film producer and has been nominated for three New England Emmy Awards and has won three NASJA Harold Hirsch Awards for excellence in journalism. Thirty Years in a White Haze is Dan Egan’s Story of Worldwide Adventure and the Evolution of Extreme Skiing. Order yours here https://www.white-haze.com/ or on Amazon.

Eric Wilbur is a journalist who has been covering the New England sports, travel, and skiing scenes for nearly three decades. His written work has appeared in The Boston Globe, New England Ski Journal, Boston.com, Boston Metro, and various other publications. He fell in love with skiing at an early age, a dedication to the sport that only increased upon moving to Vermont during his college years. He lives with his wife and three children in the Boston area. This is his first book.