I am dressed my best to do it, if that helps: a classy dress with large floral black and white print that falls just below my knees. It is strapless with a sweetheart neckline, the kind that looks good on everyone. I must have bought the dress for a special occasion, but I found it shoved in the back of my closet, unworn, tags still attached. The dress makes it appear less meaningless.

I didn’t know of my attacker until after it happened. I didn’t even realize it had happened until months later. When I woke up there was just one man standing by the bed. I heard a variety of beeps all around me and a faint consistent ticking sound that seemed to be coming either from right below my head or inside my ear. I opened my eyes and stared up at a white ceiling, trying to remember where I was. Nothing came to me, but no sense of fear clenched my chest. Glancing around I saw that the man by my bed, who looked very young, was dressed in a nurse’s uniform. He had a clipboard and was jotting down numbers from a machine. As it clicked in my head, right in time with the still present ticking, that these were my vitals, the young nurse turned, saw my eyes were open and sprinted out of my room. For a moment I was left alone in what I now knew was a hospital room with just the beeps of the machines and the soft ticking. Then a whole fleet of doctors came flooding in, surrounding me with their starched white coats and stethoscopes. They chattered to themselves, mostly in words I barely recognized as English, drowning out both the beeps and the ticks. Apparently, I was a medical marvel.

My procedure was the first of its kind, extremely experimental. They didn’t fully explain it to me until a few weeks after I woke up. In their medically professional opinions I shouldn’t have been told earlier because the information could have shocked me and sent me back into a comatose state.

My brain is half metal. It is not visible on the outside – well, except for the fact that when I woke up my head was shaved and my skull covered in scars. It was the only option they had, and it had a very slim chance of being successful, but I had no chance of survival without it. I still don’t fully understand the science, or mechanics, behind my own brain. The simplest way I can explain it, and comprehend it myself, is that I am a cyborg. However, against almost every stereotype, it doesn’t make me any smarter. I can’t do astoundingly complex math problems in a short period of time, nor can I go days without sleep and still function at peak mental performance. In fact, I think the procedure actually made me stupider. Rather than memorizing every minute, concise detail that comes within my line of vision or earshot, I lost most of my memories. I don’t remember any of my childhood. Don’t feel bad for me though, I’m not upset about it so there is no need for you to be.

The doctors and psychologists told me that I should be able to return to normal life in a couple months. They had to keep me under surveillance for so long to make sure that the wires weren’t going to malfunction or go haywire. They also had to make sure I still had my motor skills and normal bodily functions. There are only a few things I wasn’t able to do. I can’t write in cursive, I struggle to cut some food, and I cannot pick my own nose. My nurses had to help me blow my nose or use one of those little booger suckers that are designed for infants for the particularly difficult obstructions in my nostrils.

My family, of course, came to help me in the healing process. However, I found out that my dad was killed in a car accident when I was a teenager, and I was an only child, so really just my mother came to help. She tried to tell me stories about my younger years, but I didn’t pay much attention. I don’t miss the memories, so why tell me some boring story about a middle-class family that didn’t have anything spectacular happen to them. What I listened to didn’t sound like a bad childhood; it just wasn’t exciting.

When I was finally released from the hospital my mother tried to get me to come live with her, but I told her no. I remembered that I had an apartment of my own, and I wanted to go back to it. I wasn’t sure exactly where it was, but I still wanted to try to resume my old life.

My doctor-prescribed therapist said it wasn’t best for me to hear the story of my accident right away. She said I could hear it once I had fully recovered, and she would narrate it to me in increments so it wouldn’t be too overwhelming. I had absolutely no memory of what had happened to me, so during the first story-telling session, the third actual session of therapy, I didn’t know what to expect. I thought maybe I had been shot in the head, or had fallen from a great height and my head smashed against a tree or rock on the way down.

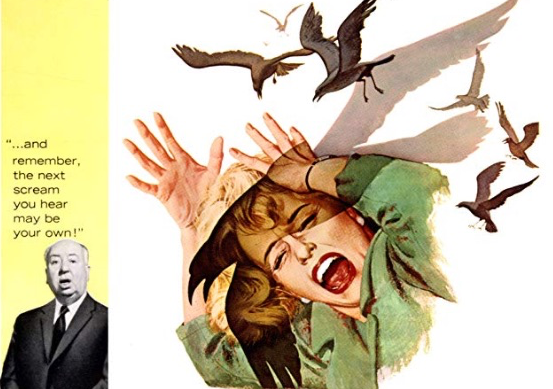

As it turns out, nature can be a vicious thing. I had been attacked by a bird. Because of one bird I was now a metalhead. My attacker was a Loggerhead Shrike. This species of bird isn’t even that rare. It is just a small creature that no one ever talks about. The first day the therapist began telling my story, all she did was inform me about this little bird. It has the nickname “raptor without talons.” She showed me a picture of the Shrike, and I felt no hatred towards it. No surge of loathing came up through my torso as I saw the small bird who, according to the therapist, forever disrupted my path of life. It has a white underbelly, gray back, black on its wings, and a black mask. This little bird eats its food by capturing it in its beak and then impaling it on some sort of spike, like a thorn or barbed wire. Usually, the bird eats insects, lizards and small mammals. I guess my Shrike was either feeling especially brave or hungry enough to come after a human.

After three sessions of storytelling with the therapist, we got to the climax of my story. She replayed bits and pieces of the news report done about my incident. Based on the reports of the people witnessing the natural phenomenon, my shrike had been watching me for a while, tracking me. When I was in the ideal spot, near a grove of rocks, some of which were pointed and sharp, the bird flew at me, fluttering in my face and pecking at my skull. I screamed and tried to protect myself, but the bird was too persistent. My skull was already bleeding profusely before I hit the rocks. According to the doctors, I was unconscious before my head hit. The bird must have pecked enough of my head to cause me to pass out. After I had hit the rocks, the bird continued to peck at my flesh, eating me. Several onlookers had filmed the incident on their phones once they realized something significant was occurring, but my therapist deemed this footage too traumatic for me to see at that point in my recovery. However, I could assume it was quite graphic and bloody, but not even picturing the image of all that blood triggered any sort of sadness, self-pity, or repulsion.

As my therapist told me my whole near fatal experience, I didn’t react at all. She thought I was going into shock, but I really felt nothing. I sat in her office silent; when she stopped asking questions and trying to soothe me, I could hear the faint ticking that always accompanied me. I realized that this was my story, and that it had been my brains splattered across the rocks, and my skin that the bird was devouring, but I didn’t feel sad, scared, distressed, disgusted. I didn’t feel any emotions towards it. I tried to explain this to my therapist, but she just kept telling me that I was in shock and kept trying to prescribe medicine to make me feel better. But I didn’t feel bad. I didn’t feel anything.

I hadn’t felt anything since I had woken up in that hospital bed with the nurse staring at me in surprise and then running out of the room. The doctors had come rushing in with excitement, panic and intrigue written all over their faces. Everyone else had been overflowing with emotion, but I stayed a blank slate.

I quit going to my therapist after I heard the peak of my story. It was all going to be about my recovery after that point, and I already knew how that ended. I didn’t want to know the mechanics of how they put in my brain. I know that it is all robotics. I can function normally most of the day, and if everything is really quiet I can still hear the faint ticking, which I now know comes from inside my head, not an outside source. What else did I need to know? The doctors assured me that it was waterproof, so I wouldn’t fry my circuits if I took a shower or got caught in a rainstorm. I knew that if I ever experienced anything out of the ordinary it would be more beneficial to go to a computer store, rather than back to the hospital. I think a robotic brain is a little out of their area of expertise.

I began to realize there was a problem when I witnessed a little girl run into the street and get hit by a car. I just stood there and watched. Everyone on the street around me was freaking out; women were crying, men were cringing. I just stood there, feeling nothing. I wasn’t sad, upset, horrified, or disgusted. I knew something wasn’t right. I knew I should have had some sort of reaction. There was no way I was still in shock from my accident.

I had looked up the symptoms of shock after my therapist kept insisting I was experiencing it. Yes, I used a computer; I may have been part cyborg, but I couldn’t access the internet through my brain. Since I had woken up in the hospital, I had felt none of the symptoms. I had given myself a self-examination, checking off each symptom on the list. No cold or sweaty skin that may be pale/gray, weak but rapid pulse, irregular breathing, dizziness, profuse sweating, fatigue, dilated pupils, nor nausea. All I felt was an absence of symptoms.

About a week later it was my birthday, or so my mother informed me when she sent a whole bouquet of balloons with a card telling me she was taking me out to dinner that night. I knew I should have smiled and been happy about the colorful squeaky balloons, or should have felt loved by my mother, but I didn’t. I put the balloons on the table, and went to get ready for dinner. When I got back to my apartment, there were the balloons. Light from outside made them seem as if they were glowing orbs splaying colors across my kitchen walls, something that should have been an inspiring sight of beauty. I reached into the drawer nearest me and pulled out a wooden skewer and began impaling the balloons one by one. With each pop shriveled carcasses filled my skewer, becoming useless latex on a stick. I looked at the destroyed balloons, their glowing colors now dull and shriveled, and still felt nothing.

This is something I should have gone back to my therapist and talked about, but I didn’t. She would try to tell me I needed medication. I didn’t need anything. I wasn’t depressed, because I never felt sad. I wasn’t in shock, nor was I traumatized, because I never felt scared, afraid, or like the world was crashing in on me all at once. I wasn’t overcome with joy or awe that the doctors were able to save my life. I wasn’t angry that this had happened to me; I didn’t feel indignation towards a God that had allowed this to happen. I had no emotions. I didn’t feel.

The doctors had made half of my brain a robot. They might as well have made the whole thing a machine. Maybe then I wouldn’t have even realized something was missing. But that real, human part of me knew that this was not the way life was supposed to be.

The human part said this wasn’t living, so the mechanical part determined that there was no point in being alive.

This is why I am writing this story of myself. I chose to send it to you because at least one person should know what happened to me. As soon as I get home from mailing this manuscript, I am going to finish the shrike’s job. I don’t want to continue this charade of life when I am getting nothing out of it, nor am I giving anything back to those around me. I am not going to go back to the rocks where the shrike attacked me. That would be clichéd. Flashy. That’s not who I am, or who I presume I once was. So I will just put on this elegant dress, then I will impale myself. I know most people wouldn’t be able to do this; they would panic and back out at the last second, but I can’t feel fear. There is nothing in my way. Just know that I dressed my best to do it, if that makes it more human.

Claire Sartin is a previously unpublished author. She received a Bachelors’ degree in writing from Eureka College, where she was also an intern at the Eureka Literary Magazine. She continues to work towards her goal of publishing more short stories and longer works of fiction.