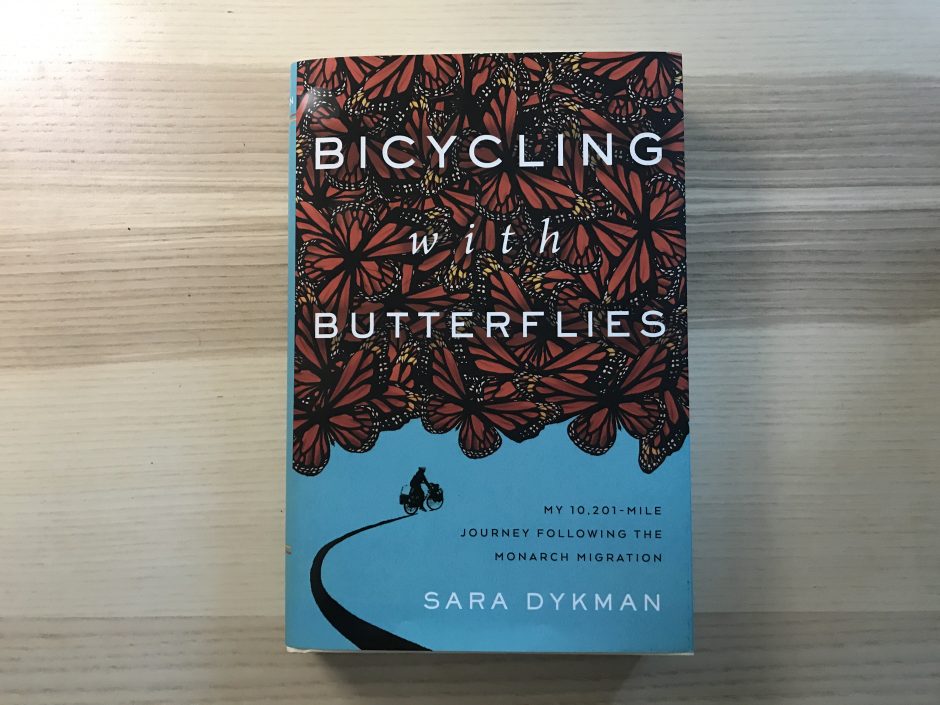

Editor’s note: Most of us are likely curious about the person who writes a book — in particular, one who rode her bicycle 10,201 miles to follow the monarch butterfly migration from Mexico across the United States to Canada and back again. So we’re introducing a new feature to our book excerpts: a Zoom interview with the author. If you like what you’re about to listen to, watch, read, please leave a note in the Comments—and treat yourself to a copy of Sara’s book. This is the best book about adventure cycling I’ve ever read, and it’s available on Amazon in hardcover, Kindle and Audible. ~ Jack

Bicycling with Butterflies excerpt: “A Million-Winged Sendoff”

DAYS 1 AND 2 / MARCH 12 AND 13

MILES 1–118

The sun’s warmth began to pour steadily through the branches, and the monarchs responded by opening their wings, every scale twinkling with gratitude. In the spotlight of spring, butterflies by the thousands sailed toward the sky as fluttering eruptions of orange. The monarchs crowded the skies, painted poems against the blue, and danced with the wind. The song of millions of wings hummed through the trees’ needles, and I felt the anticipation in their swirling flight.

As they sought water, monarchs leapt, like a parting river, from the moist ground where they pooled along the trail. When a cloud passed across the sun, the shade and temperature drop signaled to the butterflies that they might be trapped away from their colony. Suspended in air, they would wait. If the clouds stayed, they could glide back to the protection of the clusters. If the sun re-emerged, the monarchs could return to their errands: swirling in search of mates, sipping nectar, absorbing the renewed warmth, or settling back to the streams for more water. Pooling, streaming, mating, and flying were all clues that the migration was gearing up. Winter was over.

It was time to pack my bags and ride into battle—the battle to save a great migration.

I loaded down my beater bike, a 1989 Specialized Hardrock, until it was so heavy I could barely lift it off the ground. A Frankenstein bike that I had made five years earlier from a collection of used parts, it looked like a cross between a salvage yard and a garage sale. Its white and pink paint job was speckled with rust-colored dings—scars from past adventures. The bike was ugly. To me, however, it was a reliable machine, a deterrent to theft, a statement against consumerism, and my ticket to adventure. I liked the look.

Stuffed into the bags that were clipped, tied, and fastened to my bike was a collection of gear, old and new, that I needed to make the trip. Over my rear wheel, a rack held two cat litter containers I had turned into homemade bike panniers. Those buckets contained a fleece jacket, raingear, a pack towel, shower supplies, tools for minor repairs, a water-color set, two cooking pots, one homemade stove, one day’s worth of food, a bike lock, and a large water bottle. On top of the buckets were my tent, a folding chair, and a tripod, all held in place by bungee cords and a sign announcing my route and website. One side of the sign was in English, the other in Spanish.

A rack over the front wheel held two store-bought red panniers. One contained my sleeping bag, journal, book, and headlamp; the other, my rolled-up air mattress, laptop computer, and charging devices. On my handlebars was a small bag, stuffed with my camera, phone, wallet, passport, maps, sunscreen, toothbrush, spoon, and pocketknife. It all added up to something around seventy pounds. In contrast, each monarch weighed half a gram. It takes about four monarchs to equal the weight of a dime. Though people gasped when I told them what I was doing, it seemed to me

that the monarchs, with their unburdened wings, deserved the accolades. They were much better-equipped adventurers than me.

Bags packed, I waved goodbye to all the friends I had made while waiting in Mexico and pushed off. The first breath I took filled more than my lungs. After months of planning and anticipation, I was finally on my way.

There was nothing left to do but do.

Gravity carried me downward. I went fast, weaving around potholes, finding gaps in the speedbumps, and feeling the excitement of the start. Suddenly, with no warning, I went from enjoying the views to colliding at full velocity with a classic, hard-to-spot, Michoacán speed bump—better described as a moderately high curb stretching across the road. In what seemed like slow motion, I catapulted into the air, bringing my bike along thanks to a death grip on my handlebars. The ground rushed forward and I strategically braced for the whiplash of a jarring landing.

THUMP!

My wheel hit the ground, I hit my brakes, and one of my panniers was sent flying with the jolt. It hit the ground without grace and unpacked itself in the middle of the road. I laughed sheepishly, looking to see if anyone had witnessed my blunder. “Off to a good start,” I said to the empty road. At least I was on my feet. I repacked and resumed.

Reaching the bottom of the hill, I turned and started trudging right back up the same mountain on a different, more deteriorated road. I stumbled upward as the road became a mess of rock and red dust. At the sections with the loosest rubble, I was forced to jump off my bike and push. As I walked, I glanced upward. Streaks of monarchs hung above the road. Like a sign, they guided me; I became a witness to a pilgrimage of wings.

The crowd of monarchs grew from a trickle to a river. When the road turned, the current of orange gathered me in its arms. I matched the speed of the pumping and gliding wings. Neither hurried nor lazy, we could travel as one. Against a backdrop of dirt road, monarchs floated below me. Against a canvas of blue sky, monarchs soared above.

The butterflies flew, and since I couldn’t fly, I biked. After so much planning, so much dreaming, so much work, I was officially butterbiking with the butterflies. The name of my project, Butterbike, finally made sense.

Then the butterflies ditched me.

“Monarchs!” I hollered, knowing exactly how absurd I sounded. “Come back!”

Since they didn’t have to follow roads, they confidently cut through the forest on a direct route north. Following them was impossible on my bike, so I knew I would have to traverse back and forth across their path on whatever roads I could find. I wished the migrants good luck as I turned away with the bend of the road, and we headed into our divergent unknowns.

I was less capable than the monarchs of navigating the unfamiliar, and I proved it at the trip’s first intersection. When the road forked, I was presented with two choices: follow the curve of the road to the right, or turn left. Both dipped downward and out of sight.

Without a smartphone, my only option was to rely on the clues of the road, my horrible sense of direction, and my paper map. This map had been only semi-reliable on my first bicycle trip through Mexico. The creases were worn and I’d covered most of it in clear tape to protect it. What I was protecting, however, was a colorful piece of paper that was accurate about 70 percent of the time. Even if the cities were misnamed and some of the roads didn’t actually exist, I used it because it was better than nothing.

According to said map, I had to leave the sanctuaries, go east toward a town with a name I couldn’t pronounce, and take the first left after crossing from the state of Michoacán to the state of Mexico. Easy—right?

Standing at the first junction after crossing the state line, I double checked my map and chose the left-turn option. Unsure of my decision, I rode hesitantly, gripping my brakes as my bike tiptoed downhill. The slow passing of the trees lining the road reminded me I was missing an opportunity. Braking going downhill is like watching a bowl of chocolate ice cream melt rather than eating it. Basically, unforgivable.

I let go of the brakes, committing to the consequences of my navigational guess, and tucked my body into itself. Gaining speed, the trees blurred through my watery eyes, and the wind drowned out my worries. At forty miles per hour, I thought about nothing but the road ahead, analyzing each shadow for hidden potholes, speedbumps, and bowls of chocolate ice cream (you never know, right?).

Going downhill fast is my version of flying.

At the bottom of the hill, the thrill of flying was replaced by the realization that at the first intersection of the trip—literally, my first opportunity to go the wrong way—I had gone the wrong way. Confirmation of my error came with the passing of several miles, and the absence of a junction to mark the next turn. I knew where I wasn’t. I didn’t know where I was. I was officially lost.

When lost, one has two options: turn around or keep going. You can’t stand still and do nothing. Backtracking sounded torturous, so I chose to keep going. I would carry on, find a sign or a human that could tell me where I was, then revise my plan from there. Decision made, I set off, ready to accept whatever I found. Second guessing can become toxic.

Fortified by having made my first blunder, and on my way to solving it, I felt another rush of freedom. Mistakes are less scary once you have made a few. It was clear, however, as the clouds blushed with the first sign of setting sun, that I was not going to completely solve my wrong turn that day. I would need to camp, and that was fine by me. Nothing solves problems like escaping into a tent. In the morning, fresh from sleep, I could trace a new route north.

My camping options were not obvious. There were open fields of young corn, rows of spiderlike agave plants, clusters of colorful cement houses, and the occasional grove of spared pine trees. Even though I had biked thousands of miles and deliberated over camping spots hundreds of times, each night was its own puzzle.

I slowed my bike as I passed one of the mentioned options: a cluster of trees just off the road. It wasn’t perfect, but the sun had flipped the switch and the countdown was on; unless I wanted to pick a spot in the soon-to-be freezing darkness, I had to settle.

A small path just off the road took me to a flattish spot under a tree. Home sweet home, I thought as I let the weight of my bike be absorbed by the ground. Voices, mumbles of Spanish from the people walking down the road, filtered through the trees. Since I couldn’t see them, I assumed they couldn’t see me. I wasn’t scared of them, but I felt more comfortable knowing I was well hidden. My tent fit perfectly on a carpet of pine needles, and even with all my sleeping gear thrown inside, there was plenty of room to spare. It was my first long solo trip, and if nothing else, it would be nice to have a roomy tent, practically a mansion.

Two bites before finishing my sandwich, a version of dinner I had elected because cooking required more energy than I could muster, a man’s whistle and the trotting footsteps of a horse broke the silence. I could neither hide my tent, nor try to hide in my tent, so I paused to listen in the near dark.

The horse and man walked ten feet from me, on a faint trail I hadn’t noticed before. He was likely commuting between his fields and his house and would never have guessed that a woman from another country had stopped to sleep in his neighborhood. I wasn’t sure if he had spotted me, but I was sure I didn’t want to startle him.

My best Spanish greeting broke the silence. “Buenas noches.”

I took his silence for a question and followed up with a choppy explanation of what I was doing. He looked at me, through the dark, but didn’t stop. Perhaps he understood me, perhaps he didn’t. Either way, he didn’t smile or talk. He barely reacted. The only indication that I was real came from his eyes, which followed me until a low branch forced him to duck as he slipped into the night. Discovered, I had two options, pack up and find a better spot, or go to bed. I went to bed.

When the new day’s sun slid across the forest floor, any worries I’d had about my camp spot were extinguished. I welcomed the second day of my trip. Happy Birthday, I told myself. Perhaps if I had known I’d be celebrating the big three-two by biking down a terrifyingly narrow highway full of terrifyingly fast cars, I would have turned around, found a cake shop, and called it a day. Instead, I moved forward. Like a video in rewind, I repacked all my things and reloaded them onto my bike. The spot I had turned into a home for the night lay behind me, just as I had found it. Except for some flattened pine needles, no one would ever know I had been there. It was satisfying to borrow a random place, make it my home, take care of it, then return it as close to untouched as possible.

Reversing course, I headed back through the trees and picked up where I had left off. A few miles later, I reached my first junction of the day and turned right. It took only moments for the first car to pass me. I cursed as its wake sucked me and my bike toward the middle of the road. I braced, cursed some more, and kept going. Car after car, my stress grew. Mile after mile, my doubt grew. “This is not fun,” I told the thousands of miles of road that extended like a paved plague before me. It was only Day Two. What had I committed myself to?

Doubt is as much of an adversary on a long trip as tired muscles are. However, just as legs can be conditioned to carry one farther, a mind can be conditioned, too. The key, at least for me, was to ignore the big picture. Never project thousands of miles into the future. Instead, think about the next mile, the next town, or (best of all) the next meal. In this way, I could confront small distances, and celebrate strings of tiny victories that would soon add up. I knew this strategy because I was not on my first long trip. I had already pedaled thousands of miles, including a twelve-country bicycle trip from Bolivia to Texas and a forty-nine-state tour around the United States. What these trips had in common was the sense of impossibility that lingered at the start. Before each trip, people told me my dream was not attainable, that I would probably die. Before each trip, I worried that I would fail. But by continuing, I had proved each time that a mile is a mile, regardless of how many are strung together.

I celebrated my birthday and my survival by ending my day long before the sun did. After sixty-five car-crazed miles, my mind, legs, and butt were all pleading, STOP!

An abandoned road ran like a shadow alongside the newer highway. Old roads can make great campsites, and this one was no exception. Blocked to cars by a few boulders, the road extended out of sight. It had a gradual slope, but I knew that I could stuff my rain jacket under my air mattress, like a retaining wall, and turn the hill into something resembling flat. With some loose rocks, I staked my tent on the pavement where cars had once sped. Sitting on the centerline, I ate another sandwich. Dessert was a birthday chocolate, a gift from Brianda.

***

Sara Dykman is the founder of beyondabook.org, which fosters lifelong learners, boundary pushers, explorers and stewards. She works in amphibian research and as an outdoor educator, guiding young people into nature so they can delight in its complicated brilliance. She hopes her own adventures–walking from Mexico to Canada, canoeing the Missouri River from source to sea, and cycling over 80,000 miles across North and South America (including the monarch migration trip)–will empower young and old to dream big.

Excerpted by permission from Bicycling with Butterflies Copyright (c) 2021, by Sara Dykman. Published by Timber Press,Inc., Portland, Oregon. All rights reserved.