As we approach National Poetry Month, April 2024, we have many wonderful works to share with you. We begin with this, Michael Larrain’s return to The Fictional Café with an epic poem he has worked on for many years. We’ll be publishing one Part per week over the next six weeks. How did such an interesting – indeed, extraordinary – poetic work come to be? We’ll let Michael tell us all.

“When I began The Life of a Private Eye, I had no idea it would grow into a series or anything more than a single poem. As the material for Part 2 was arriving, it took me a while to tumble to it being a sequel to Part 1. As the series grew, eccentrically, each part taking me completely by surprise, the pieces relaxed from poetic lines into what were clearly sentences which I allowed to lie on the page in the manner of poetry because I liked the way they looked. A new form was developing and I thought, apart from needing a name, I should leave it as it was. I toyed with different subtitles, finally settling on the term “noirvelettes,” which struck me as an agreeable commingling of a mystery story and a novella.”

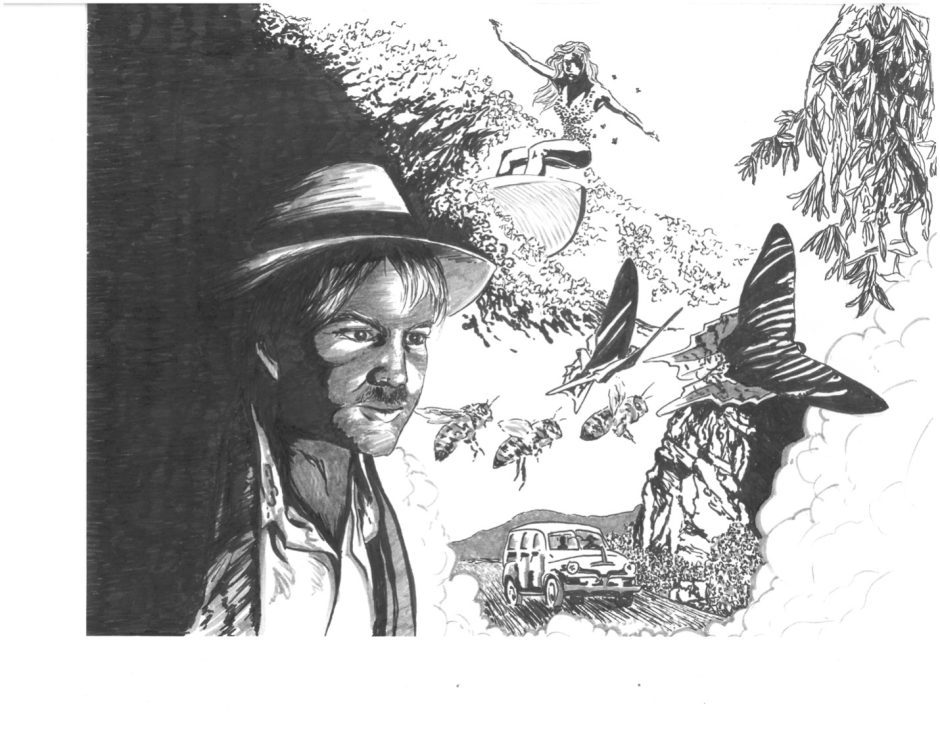

Read on to enjoy Part I of The Life of A Private Eye: A Collection of Noirvelettes. Original art was created especially for the poem by Katherine Willmore. And please a comment – we would love to know how you like it.

The Life of A Private Eye

for James Crumley, in memoriam

Part I

Lately

I’ve been finding smooth round stones

in my pants pockets

and naturally assumed I had slept on the beach,

been awakened by the incoming tide

and washed up at a seaside diner

where the waitress called me sugar

(though my clothes were crusted with salt).

She slides a mug of coffee along the counter to me

and the woman down the way

who looks a little like Veronica Lake might look

if she were trying and failing to look

like Humphrey Bogart with a hangover

opens her trench coat and shows me

that god is still at the top of his game,

then slips a small silver flask

out of the inside breast pocket,

tilts it back and forth and

jerks her head at the exit.

Along the sidewalk are people

holding all their belongings,

their worldly goods in their arms

and looking around as though

a place to live might be found

in the lower chambers of the upper air.

“I used to keep the sea in this flask,” she said

with a rueful smile, “so I could drink and

float on my back at the same time. But now . . ..”

Her voice trailed off. She didn’t seem to be

talking to me, in any case. She cinched

the coat against the wind off the ocean,

took out the flask and handed it to me.

“She took out the flask and handed it to me.”

The cold vodka hit my blood stream like

a young blonde touching down on a ski slope at dawn.

We passed a dark alleyway

strewn with garbage and dead winos,

leading to dazzling beaches

where beautiful girls were surfing nearly naked,

balancing big umbrella drinks on their boards.

The most stunning wore a one-piece made of bees.

She was a humming golden blur above curling blue water.

But if you tried to walk down the alley

to get to the beach, the girls, the umbrella drinks,

sinister forces gave you no end of grief.

A few steps in, you found yourself on a

tributary of the alley, a shortcut to nowhere,

or, rather, somewhere you had been before

but not in person.

Eventually I wised up and realized that every one

led you into a different movie.

With my luck I would always play a butler.

I didn’t want into the picture business anyway.

I preferred hoofing it aimlessly up the boulevard

with the trench coat babe, fingering

the round smooth stones in my pockets.

Having already seen her naked

(the lightning flash that reunites

the origins of time with the end of all that is)

took the edge off my need to see her naked.

Now I was free to luxuriate in her company and conversation.

**

All around us were tenements undergoing

very slow demolition, the wrecking ball

a destruction-bent comet heading for a planet

as yet unborn, no hurry, baby, don’t worry ’bout a thing.

The squatters were Talmudic scholars,

safe-crackers, conga drummers. She

spoke of her father, her first love, the mother

she had lost, the daughter she could not find,

the pattern of the wallpaper in her room

when she was little, her fear that she was

trapped there now, in the wallpaper.

The salt in the air was the promise of future sorrow,

she explained, handing out playing cards

to the homeless folks on the sidewalk,

a four of clubs to the washed-up movie star

whose name was no longer remembered,

a three of diamonds to the crazy old woman

who played the ukulele so beautifully

and sang in the voice of a crow,

a queen of spades to the down-and-outer with immaculate nails

dressed in a very old tuxedo and a battered fedora.

“Gotta go, my shopping cart is double-parked,”

he said, but stayed. “Our parents were missionaries

in China,” he told me. “My mama was a fortune-teller and a whore

who foretold her own downfall, then turned

to preaching against fornication and strong drink.”

**

My companion ruffled the man’s hair affectionately.

“This is my brother, Jacob,” she said. “He’s out looking

for our daddy, a prophet of doom who

tap-danced as he roared out the bad news

to the uncomprehending Chinese in Kowloon.

They ate it up, couldn’t get enough.”

“So long, Deli,” he said, and pushed off, but not

before pressing two canned goods upon me.

“Short for Delilah,” she said. I’d noticed

that his cart was filled with nothing but cans

of pineapple slices and artichoke hearts

and that he’d given me one of each. “Is he on

some kind of special diet?” I asked her. “No,” she said,

“He’s not even homeless. He just never goes home.

He wanders around looking for our father, who is, or was,

uncommonly fond of artichoke hearts, and my daughter

who dotes on pineapple slices. He hasn’t had

any luck so far, but by nightfall most days he’s traded

the artichoke hearts and the pineapple slices for leads

to their whereabouts.” “Did she run away?” I said.

“We had what you might call a ‘falling out.'” she said.

“It was my fault. I would look at my girl and think,

‘Where do you put the water when

the vase is already filled with light?’

Then we quarreled and before I could apologize,

she vanished without a trace.”

“What’s her name?” I said.

“Well, her given name is Lorelei,

but I’ve always called her Honeysuckle,

because swarms of bees used to follow her around

when she was little, as though

she were made of wildflowers,” she said.

“But they never did her any harm.”

Then I began to put it all together. The alley, the one-piece

swimsuit, the pineapple slices in the umbrella

drink of the girl who was a golden blur

above curling blue water. The sign that read “Wildflower Alley.”

“My fee is a hundred dollars a day,” I said,

“plus expenses. But we could forget about

the money. I already owe you a drink.”

The look of gratitude she gave me

more than made up for anything I could ever say,

do, think, care about or work my ass off trying to figure out.

Now I knew what I had to do, go down that wretched lane,

stay out of the movies, find the girl, reunite her with her mama

and somehow get home in time to tuck my own daughter in.

The trench coat babe slipped me the flask as I was

setting out. “For luck,” she said, in a throaty whisper,

“If you find my Honeysuckle, you can keep it.”

**

It was the damnedest alley any man ever stepped into,

A creek cutting across it diagonally,

coming out of one wall

as sweet as you please

and disappearing into the other,

the walls themselves were covered with wildflowers

growing out of solid brick.

I felt the dead crowding around me,

trying to take a selfie with the living.

Outside, it was mid-morning,

but if I looked overhead

I saw the night sky, the stars

opening like switchblades that would

cut you from your first kiss to your last words.

I wet my index finger and drew a line against the sky

at the identical angle the creek crossed the alley.

Call it a hunch.

A slanting channel of illuminated carbonation appeared in the water,

indicating where it would be safe to ford the little stream.

The water was close to freezing

so I took out the flask and knocked back

the last of the vodka. On impulse, I held

it down in the creek and let it fill with cold water.

I hear you’re supposed to hydrate.

The cuffs of my pants were soaked again

but it didn’t seem to bother

the family of wild turkeys

who walked by without a care.

When I stood in the entrances to the tributaries and concentrated

hard, I could tell

which movies they led to: spaghetti westerns, espionage pictures,

romantic comedies, screwball comedies, silent

comedies. I was tempted for a second to wander

into Shanghai Express (1932) with Dietrich,

Clive Brook and Anna May Wong, directed by Von Sternberg.

I’d never been in black and white.

But I kept going toward the beach.

Just as I was about to step out of the alley

a black 1937 Cadillac pulled up,

blocking the way. I couldn’t see the driver’s face

but in the passenger seat was on old man

with hair like a white campfire

holding an intricately carved oak walking stick,

a shillelagh, really, out the window

and pounding it on the roof for emphasis.

“If nude girls flew above us in the sky

performing the laziest of figure-eights

on the airiest of roller-skates

we would look more often to the stars

but instead we concentrate

on staying out of bars,” he said,

and banged his shillelagh

on the roof of the Caddy again.

On impulse, I held out one of my canned goods to him.

He regarded it like the baby Jesus

with a lottery ticket taped to his forehead.

“Praise the lord and pass the artichoke hearts,”

he said, and I offered him a sip of water

from the flask. “That’s the best damned vodka

I’ve ever tasted,” he said, actually smacking his lips.

But I had killed the vodka and refilled the flask

from the creek, with water outside

the illumined panel I had used to cross. Apparently,

the creek was a natural, or supernatural, distillery

and ran pure moonshine. From now on, I’d better

stay the hell away from Wildflower Alley.

There was no need to ask who he was,

not after I glanced down and saw the old

but still elegant tap shoes on his feet.

A bee flew by me, headed for the waterline.

I said my goodbyes and set out after it, as

though a humming had taken me by the hand.

**

She looked so much like her mother

that from a distance of twelve feet

you couldn’t have told them apart,

except that Delilah’s hair was

cropped short and Lorelei’s fell in

drenched waves to the dimples in her back.

She had just completed a perfect ride

deep in the curl of of a twelve-foot tube,

planted the end of her longboard in the sand

and leaned against it negligently.

The one-piece had been discarded

in favor of a bikini, also made of honeybees.

Her suit made conversation difficult,

what with the constant blur and motion of the bees.

Every once in a while, one would fly off

on its appointed rounds, but they always returned.

“What are you doing out here?” I said,

after explaining why I was there.

“Your mother’s been looking all over for you.”

“I’ve been looking for my uncle,” she said.

“He’s out looking for your grandfather.”

“I know where my grandfather is,” she said.

“He’s out looking for my mother.”

I must be the Einstein of stupidity, I thought.

They’re all moving in a circle, like the pirates

and Indians in Peter Pan. If I can just

get one of them to stand still for a while,

everyone else will bump into him.

“Do you know who the driver is,

the one at the wheel of the old Caddy your

daddy is riding around the boardwalk in?” I said.

“I’m not at liberty to discuss it,” she said. “But it’s the

real reason I ran away. I provoked the argument

with my mom and then used it as an excuse.

I wanted to see if I could make it all come true.

And find out if the waves were breaking left or right.”

**

It wasn’t hard to spot the Caddy. It was

the only car parked with its tires on wet sand.

He was standing on the running board in an ice-cream suit,

doing a righteous cha-cha with a cocktail shaker,

the sunlight flashing off the white sidewalls

and the wire wheels sparkling

in call and response to crashing surf.

His companion, the driver, was sitting inside

wearing a bee-keeper’s hat, and heavy gloves.

I slid in beside her as she lifted the veil

to take a sip of her martini, nodding her approval.

The sight of her face told me even before she spoke

who was chauffeuring the old charlatan around.

“Our moonrise ritual,” she said. “Pardon my bizarre appearance.

I have to wear this rig when I’m around my granddaughter.

A bee sting would send me into anaphylactic shock.”

“It may not be my place to ask,” I said,

“But I got the impression from Delilah

that her mother had passed on.”

‘That’s what she believes,” she said,

eyeing a snowy egret that had landed on the left front bumper.

“Years ago, I found my husband in a compromising situation with

one of his young Chinese converts.

She was in a state of advanced undress,

and they were both speechless when I walked in on them,

guilt writ large upon their faces in English and Mandarin.

I didn’t bother demanding an explanation, just left him

then and there, and took myself off to sort out my thoughts.

Later, when I found out my husband had been set up,

that the naked Chinese teenager, a pretty little thing,

was an agent of the Baptists trying to muscle in

on his congregation, I was flat-out mortified. That was

how I had first met him, after all.” She sighed.

“It’s like the gunfighter racket. There’s always

some new slut in town, looking to make

a name for herself. How could I face

my family again after falsely accusing my husband,

who may be a rascal and bit of a loon, but he’s a good man who

believes his own foolishness.

I faked my death by having an obit published

in a small paper on the Ivory Coast of Africa,

where it’s important to get bodies in the ground in a hurry,

so that no one would have time to attend a funeral. And I paid

an old friend to erect a marker over the supposed grave.”

“But how did you get here from wherever it is you went?”

“I had learned the secret from my granddaughter.

It’s a sort of water-borne tin-can telephone between worlds.”

“And how did your widower learn you were still alive?”

The old man leaned in through the window

and offered me a martini, ice cold, straight up, no olive.

“At the instant of my death,” he declaimed,

“I will be translated into fourteen languages:

fox, fog, railroad train, tree frog, typhoon,

empty saloon, tenor sax, shorebird tracks,

emperor whale, filling sail, rising tide, lowering sky,

coyote cry, and the mysteries of a woman’s heart,”

“Every time he delivers that speech,”

the beekeeper whispered,

“He changes all the languages.”

“But to answer your question,” he said.

“I saw the love of my life, she whom I’d thought

was lost to me forever, strolling down the boardwalk,

veiled, in a white caftan, as though she’d returned as

a ghost whose walk I would have known anywhere.

I proposed to her again, thinking

she’d be my wife in her own afterlife.”

“Are you planning on telling your daughter

that you’re alive?” I asked her.

“Yes, and soon. But we wanted a second

honeymoon first,” she said. “It’s like young love

in an old body, and even more fun

because we have to keep it from the children.”

**

But there remained the problem

of how to get Lorelei and her grandfather

from the beach to the other side of town

which seemed to exist in another dimension.

Her grandmother declined to make the journey

on the grounds it would be undignified. She

would stay in the small waterfront hotel where they’d

been enjoying their post-posthumous, doubly-marital

and happily unreformed love affair and wait for

her husband and daughter to join her later.

“We can’t go through Wildflower Alley,” Lorelei said,”

“Only one man’s ever come out of it alive.

Say, how did you get here anyway?”

“Oh, I kind of drifted in on the tide, like a note in a bottle.”

“And we can’t swim around the point. There are vicious

undertows you don’t want to mess with.

But I know a sort of secret passageway,” she went on.

“About a quarter of a mile offshore,

There’s a blue hole that goes down almost

three hundred feet, where it opens into

a series of submerged caves that run beneath

the town. If we swim through the caves,

we can re-emerge just out past

the breakers on the other side.”

She issued diving equipment to her

grandfather and myself, and we went to

Where the Sea Weeps Itself to Death.

When we walked back out of the ocean,

we were right in front of the diner

where I’d breakfasted a few hours before.

I had cut off my trousers just above the knees

and the round smooth stones were still in my pockets.

Needless to say, I was barefoot. You don’t want to

go slapping down the boulevard in diving flippers.

**

“I hear that only one man has ever made it through

Wildflower Alley and lived to tell the tale,” I said

to the preacher man, failing to mention that

we’d become brothers of a kind. I shook the flask at him,

“How would he have done that, do you suppose?”

“I never set foot in the alley,” he said, “I rode the currents

of the creek from the mountains down to the seashore.”

“How did you keep from growing

too polluted to even float?” I asked.

“It’s like anything else,” he said, taking a pull,

“You build up a tolerance. I had a vision of my

granddaughter, with a light behind her. It turned

out that the light was my wife, the very light of my life.”

**

The trench coat babe was in her old place

at the end of the counter, leaning against the wall,

her hands jammed into the pockets,

squinting out from under her hat brim.

But her eyes opened wide at the sight of Lorelei

and her grandfather. “How did you find my daughter?”

“Oh, I just followed the honey.”

“And my father, too. You’ve unearthed my entire past.”

“That’s me, always thinking five moves behind.”

I reckoned I had tipped my hat to the lady

by way of saying goodbye, then gone on a

five-day bender with the old preacher, which would

explain my blacking out the whole episode afterwards.

That’s how I figured it had gone down, anyway.

But the truth, as it happened, was quite otherwise.

My own girl child (as she confided to me while

I was telling her sweet dreams that night), thinking,

Where do you put the water when

the vase is already filled with light?

had been picking up the round smooth stones

from the rock garden

in our front yard and slipping them

into my pockets as a joke while I slept.

If it weren’t for the slightly damp ace of hearts

I found in my back pocket before turning in,

and the Mexican silver flask

and the visions of all the characters’ futures

I glimpsed in the wallpaper of her room,

I’d think I had been on the wrong case the whole time.

Such is the life of a private eye.

Next week: Part II

Michael Larrain is the author of 20 books of poetry, prose fiction and children’s storybooks. He was born in Hollywood, California in 1947 and currently makes his home in Sonoma County. His writing has appeared often here at The Fictional Café.